A new study shows how government-collected “anonymous” data can be used to profile you

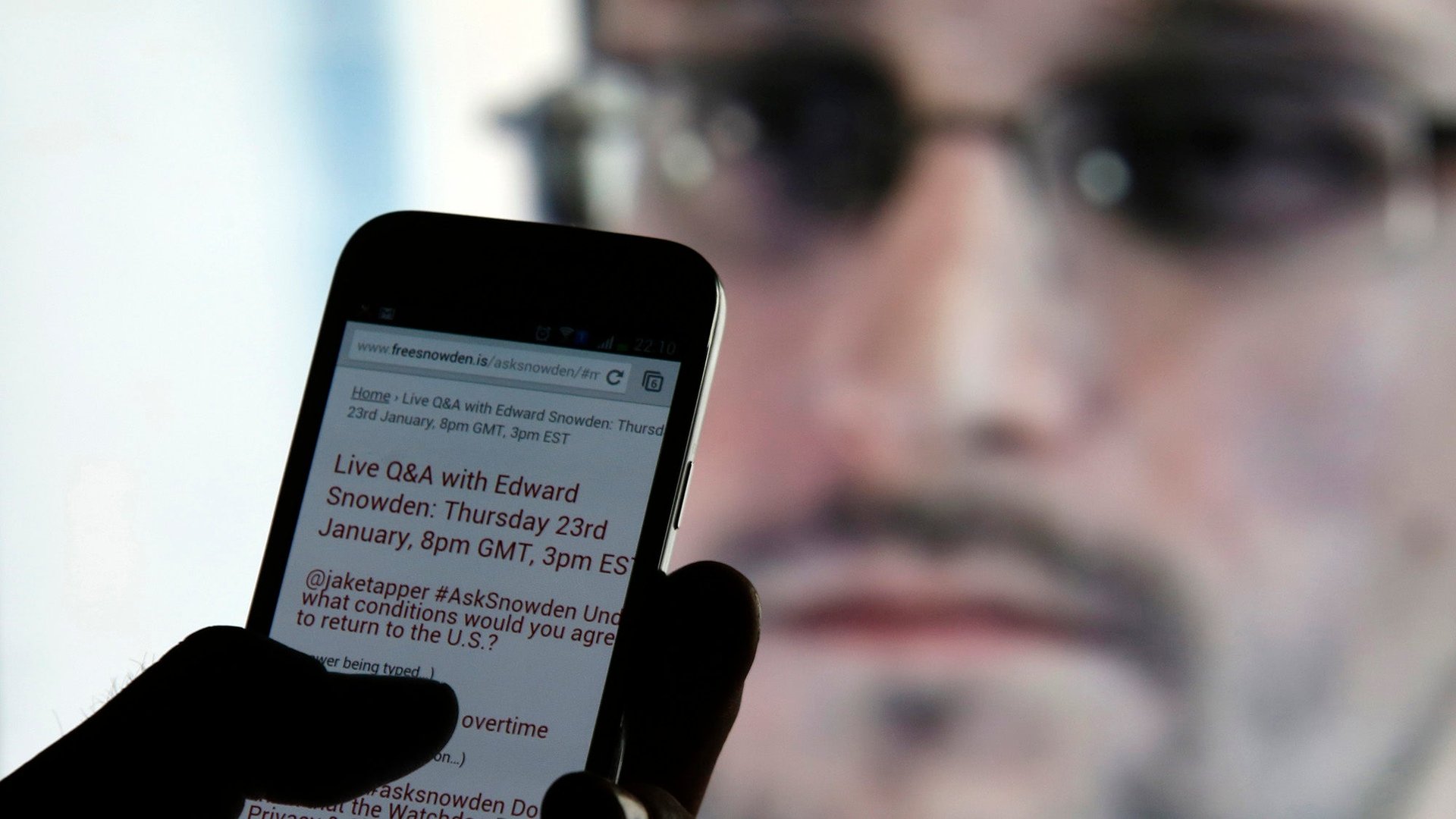

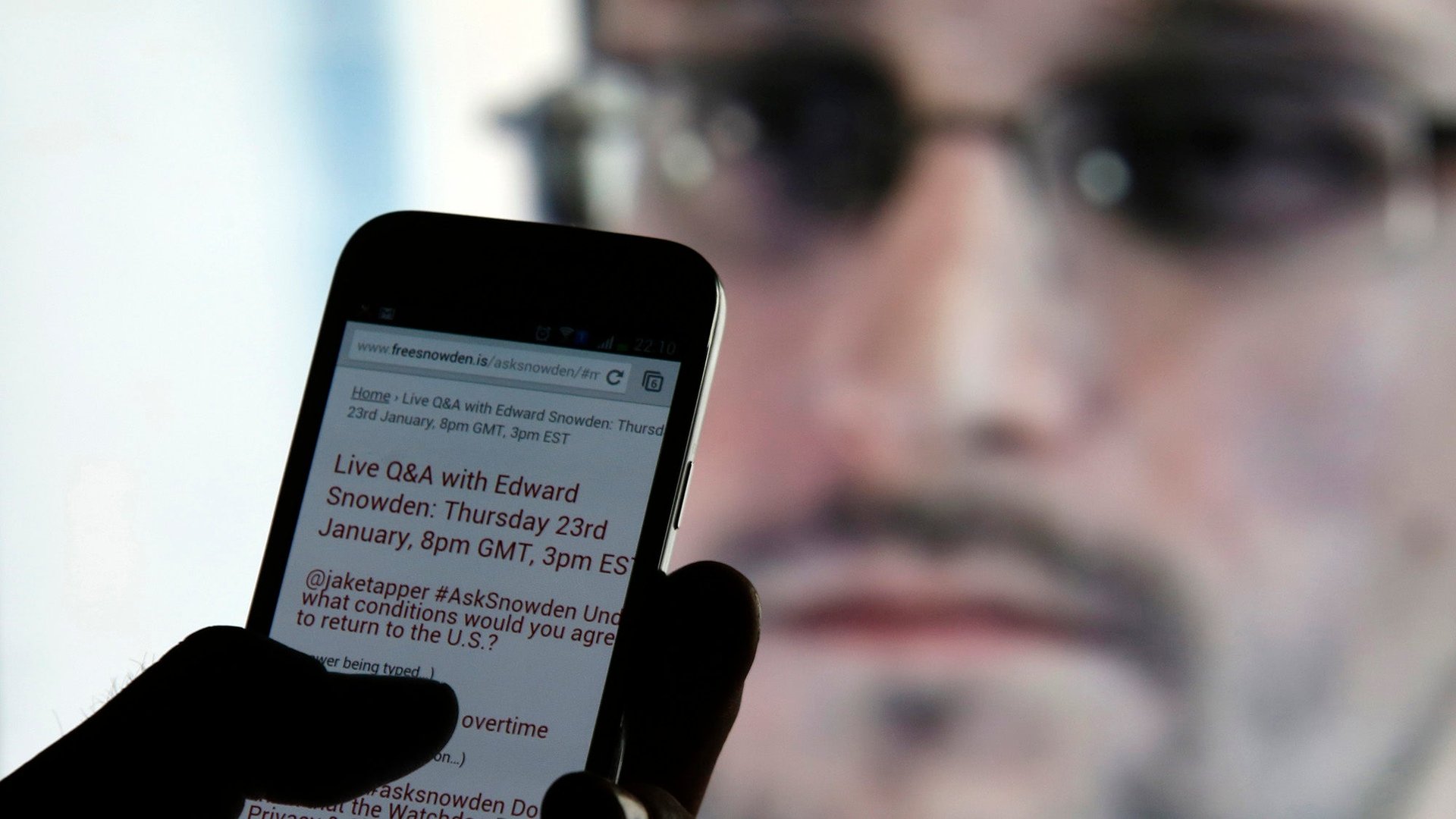

After Edward Snowden, a former National Security Agency contractor, showed the world that intelligence agencies in the US and the UK were monitoring call records on a massive scale, there was a collective gasp, but then mostly silence. There was outrage at the discovery that elected governments had been snooping on law-abiding citizens, but there was also confusion about what information, exactly, those governments were gathering, and what they could use it for.

After Edward Snowden, a former National Security Agency contractor, showed the world that intelligence agencies in the US and the UK were monitoring call records on a massive scale, there was a collective gasp, but then mostly silence. There was outrage at the discovery that elected governments had been snooping on law-abiding citizens, but there was also confusion about what information, exactly, those governments were gathering, and what they could use it for.

In its defense, the US government has said that it only collected data about calls—“metadata” that includes when they were made, to whom, and how long they lasted—but not the content of those calls. The government argued that this data is anonymous (“They’re not looking at names and they’re not looking at content,” president Barack Obama said). It is only used to “find connections that people are trying to hide,” NSA’s deputy director Rick Ledgett told TED, adding, ”Metadata is privacy enhancing.”

But the problem is that in the mass collection of metadata, it is highly likely that ordinary citizens’ privacy can be breached, and then anonymity becomes a moot point. A new study shows just how easy it is to do that. When researchers at Stanford University compared call metadata collected from some 800 volunteers with publicly available data on the internet, they were able to accurately identify more than 80% of them. The results of the study have been published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The researchers installed an app on the Android phones of 823 people who agreed to have their call metadata collected. The app paired the information with the volunteers’ Facebook accounts, which the researchers used to check for accuracy of their results. In total, they collected metadata on 250,000 calls and 1.2 million text messages.

When the call metadata was combined with publicly available data, the researchers were able to find not just the individuals’ names, but also the names of their partners and where they lived. Beyond that, in some cases, the data revealed other sensitive information: one person’s ownership of a rifle, another’s health condition, and a third’s plan to grow cannabis.

The conclusions were based on common sense, as one case outlined in the paper illustrates: The call records of a participant showed that he or she made a long call to a cardiology centre. Next, he or she spoke to a medical lab. Then he or she answered calls from a pharmacy. Finally, he or she called a hotline number for abnormal heart-rate monitoring devices. The researchers concluded, correctly, that the person was suffering from a heart condition that caused irregular heartbeats.

“All of this should be taken as an indication of what is possible with two graduate students and limited resources,” Patrick Mutchler, one of the author’s of the study, told the Guardian. “Large-scale metadata surveillance programs, like the NSA’s, will necessarily expose highly confidential information about ordinary citizens.”

The leaked documents revealed that the US government had access to the call metadata of tens of millions people. Since then, restrictions have been added on how big a net the government can cast and how long it can store the call data. But experts and privacy advocates say that these restrictions don’t go nearly far enough to safeguard ordinary citizens’ privacy.