Uber’s rivals in Africa promise happier drivers, traffic jam deals and even price haggling

Wherever there is a car, a decent road and a reliable GPS connection, there is Uber. This may not be Uber’s official strategy, but the ride-hailing app’s international growth has led to the kind of ubiquity that has turned a brand into a verb.

Wherever there is a car, a decent road and a reliable GPS connection, there is Uber. This may not be Uber’s official strategy, but the ride-hailing app’s international growth has led to the kind of ubiquity that has turned a brand into a verb.

Uber’s ever-increasing global footprint has made its way to Africa in recent years, where it now operates in 11 cities (in Egypt, Kenya, Nigeria, Morocco and South Africa) and is planning to launch in Ghanaian capital Accra soon. Uber’s ride in Africa, since opening in Johannesburg in August 2013, has not been a smooth one.

Like elsewhere around the world, Uber’s disruption of the local metered cab industry has been met with resistance and regulation disputes. In Egypt, South Africa and Kenya, Uber’s presence has sometimes led to violent protests by rival local taxi drivers. In Nairobi at least two Uber cars have been attacked and set alight, one with the driver still inside. Uber drivers have also been attacked in Johannesburg, with one such incident last month leading to Uber temporarily suspending its service in the Sandton neighborhood. Uber drivers have not only feared for their own safety but also protested Uber cutting driver tariffs in order to lower fares for customers.

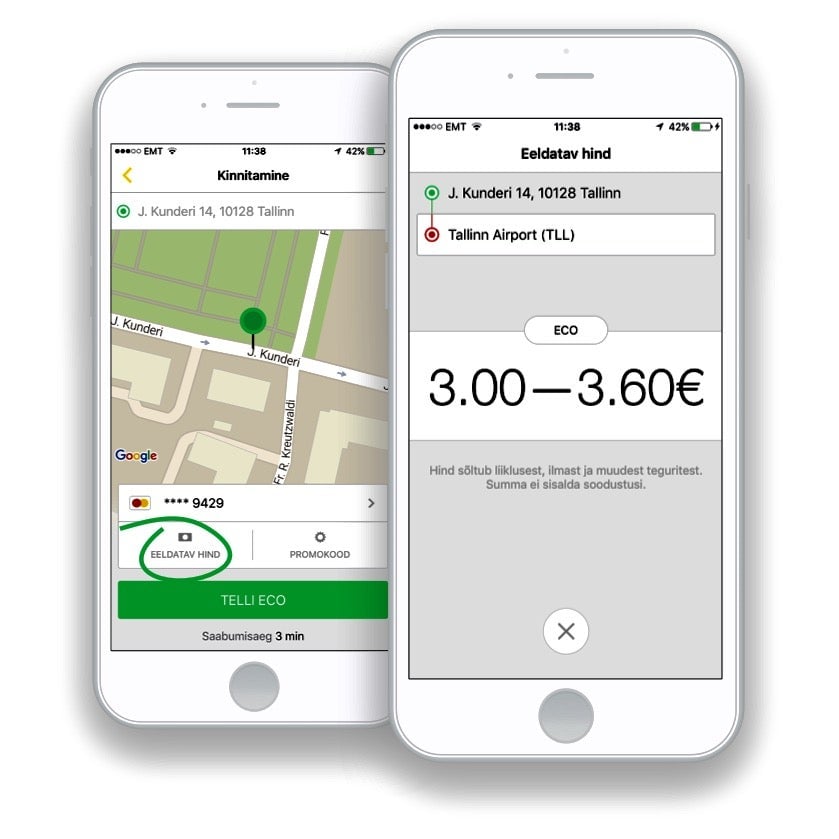

Tapping into dissatisfaction with Uber seems to be the unofficial expansion strategy of the app’s competitors in Africa. More and more ride-hailing services are identifying chinks in Uber’s $62.5 billion armor and using that to their advantage to expand into the African market. Take Taxify, the Estonian ride service that spotted an opportunity among disgruntled drivers in South Africa.

Taxify launched in Cape Town in April and expanded to Johannesburg in May. Their rates are higher than Uber, but Taxify believes it has a winning strategy: Be nice to drivers.

In April, when Uber South Africa announced a nearly 20% cut in its tariffs, drivers went on strike, marching to the company’s local headquarters. In South Africa where labor law is in the employee’s favor, Uber drivers’ working conditions have come under scrutiny.

“We’ve tried different approaches in multiple countries and we see that if you have a good service for a good price, we will have no problems getting clients,” Taxify’s head of marketing Pavel Karagjaur said. “Everywhere we focus on the drivers.”

Saudi Arabia-based cab service Mondo Ride has targeted Kenya and Tanzania as favorable locations for their first expansion outside of the Middle East. In adjusting to the local market, Mondo Ride also makes use of boda bodas, local motorcycle taxis. They’ve also promised to avoid surge pricing.

Local developers are also making a go of it. Kenya’s Maramoja launched a year ago with the promise of a deeper understanding of the country they operate in, because it’s their own. Claiming an intimate knowledge of Nairobi’s grinding traffic, Maramoja charges according to zones. The app also tries to tap into users existing networks, recommending drivers through social media favorites via friends or followers.

“Kenya doesn’t have a taxi market, it has a taxi culture. And Kenyans aren’t a consumer group, they are a community,” Maramoja said on their blog. “People’s stories and networks matter because more than anything, they are what people trust and what drive their decisions.”

But Maramoja ran into a series of technical glitches, making its Android and web app a pain for users, until a recent update. In Nigeria, Afro had similar glitches since it’s inception in 2012, which eventually lead to a rebranding—from Afrocab to just Afro—and a back to basics approach to make an app with Nigerians in mind.

The homegrown app’s smartest feature is that it literally haggles—tapping into the shopping culture of Nigerians. A prospective user and driver negotiate a price using the plus and minus signs on either side of a proposed price, until they agree on the fare. It’s a nod to a market practice that many Africans are proud of.

Afro will have to compete with Oga Taxi, which bills itself as Nigeria’s “first and biggest taxi app.” Oga—Pidgin for “boss”—ranks safety as its top priority, promising thorough background checks on drivers and users and even providing a built in SOS-button.

The scramble for Africa’s passengers has been a bruising race for some. The South American Easy Taxi has reportedly had to bow out of the African market, unable to compete with Uber. Funded by Africa’s first e-commerce billion-dollar ‘unicorn’ Africa Internet Group, Easy Taxi operated in Nigeria and Kenya, where it was the most downloaded app at one point. But with the arrival of Uber in those markets, Easy Taxi appeared unable to compete. Ironically both Uber and Easy Taxi’s parent AIG/Rocket Group were both funded by Goldman Sachs.

While Uber has inspired a series of new players in the market, none of them have made much of a dent in Uber’s expansion in Africa. It remains the most ubiquitous hailing app and has both Kenyan and South African government officials on its side in clashes with metered cabs. It also had incredibly deep pockets—this week it just received its largest ever single cash infusion of $3.5 billion from Saudi Arabia.

Ultimately, Uber’s adaptation to regional markets, like the introduction of cash payments, gives it local flexibility with global clout. For both investors and drivers, Uber is the most reliable ride-hailing app in Africa, for now.