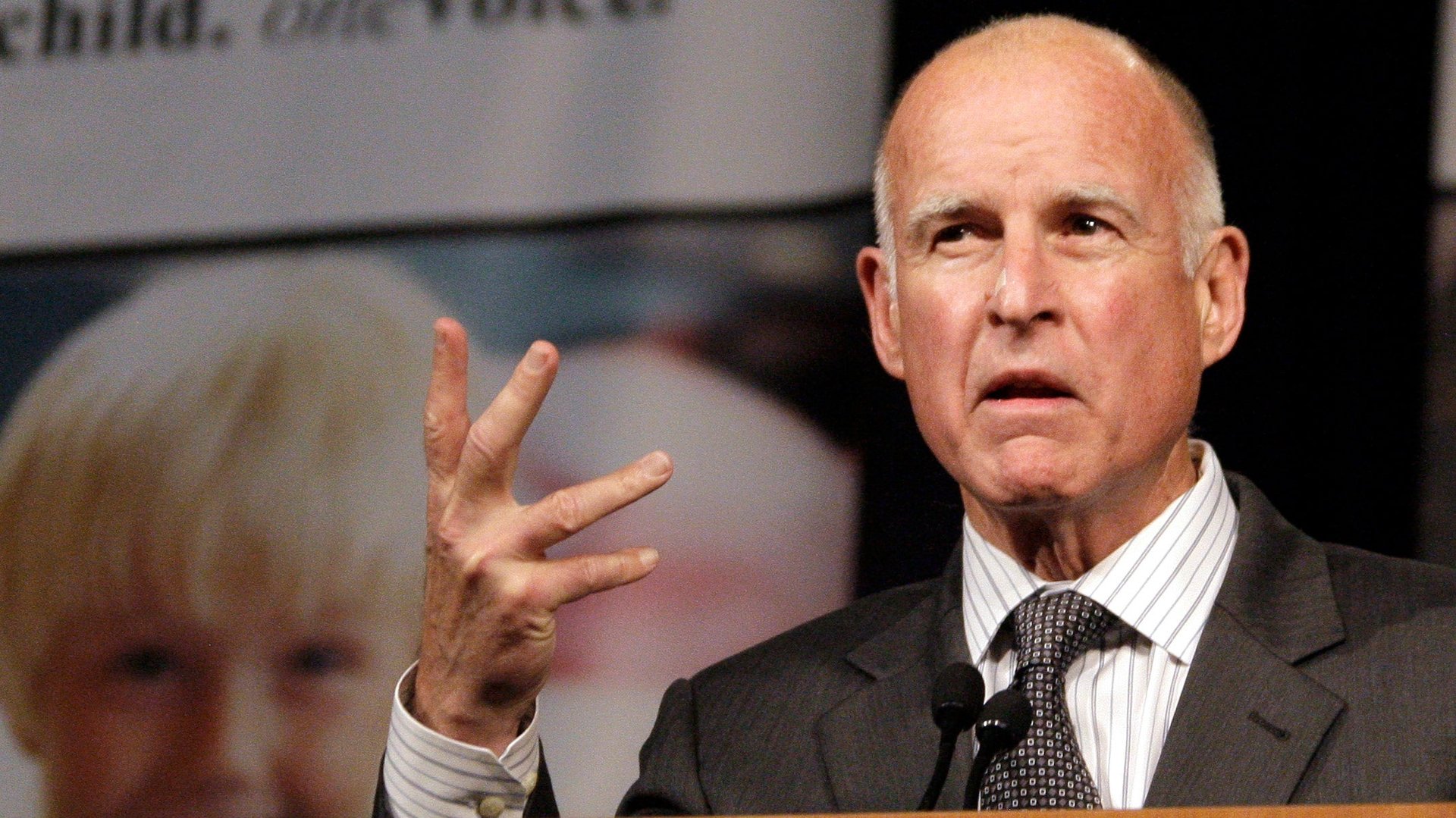

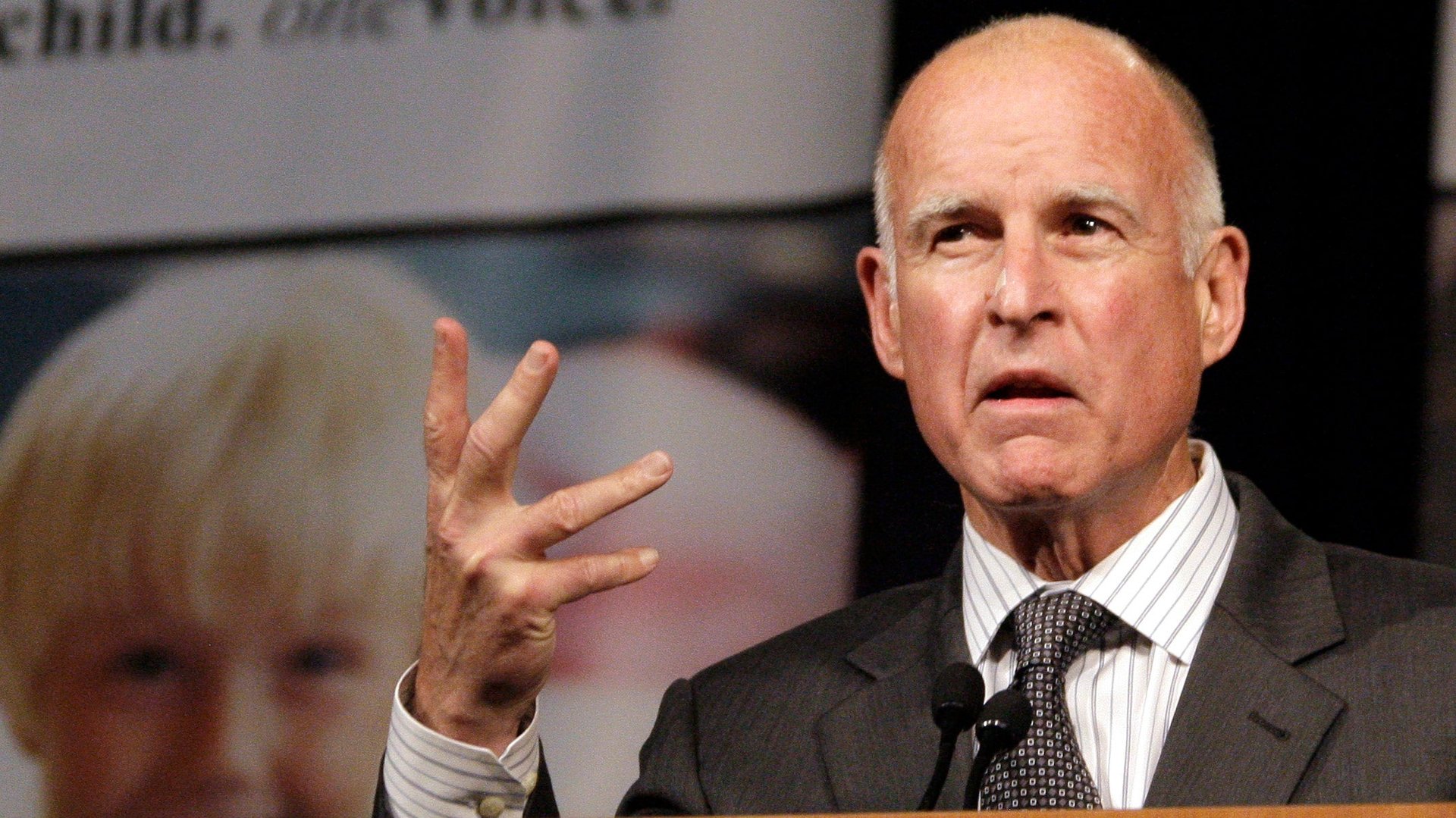

California governor Jerry Brown’s plan for cheaper rent is going to make people upset

California Governor Jerry Brown’s long political career has seen many battles, but the governor who turned around California’s insane budget and riled up the Bernie Bros by endorsing Hillary Clinton is taking on perhaps his toughest political opponent yet: The NIMBY.

California Governor Jerry Brown’s long political career has seen many battles, but the governor who turned around California’s insane budget and riled up the Bernie Bros by endorsing Hillary Clinton is taking on perhaps his toughest political opponent yet: The NIMBY.

Not In My Backyard is the pejorative term of art for city residents who fight development to protect their home values or neighborhood culture. Whether in the form of wealthy residents trying to keep low-income renters out of their neighborhoods or community activists who fear that new development will push the poor and minorities out of cities, both groups use zoning and environmental reviews like cudgels.

Yet urban planners and economists argue that restrictive building rules are a primary reason that urban rents in many prosperous US cities are so high that they are driving away even middle class residents. The problem isn’t what kind of housing is being built, they say, but simply that so little of it is in production.

In Bay Area around San Francisco, where jobs in the technology sector have attracted droves of new migrants, the last decade has seen six new residents arrive for every housing unit built. That pattern has made rents soar.

Brown is pushing a plan that would allow developers to leapfrog planning and environmental reviews if they meet basic zoning requirements and set aside 20% of their units as affordable housing, or 10% in developments near public transit.

Brown’s plan could defeat local rules such as those illustrated by the LA Times’ Liam Dillon. Dillon found one San Francisco property owner who has tried to convert his laundromat into an apartment building for more than two years. So far, the laundromat owner has been thwarted by resident objections that say it will not provide enough low income housing. Another nearby project intended entirely for low-income seniors has been held up over concerns about nearby views.

Researchers say that local zoning rules contribute to segregation by income and race. One 2015 study of 95 US cities (pdf) found that wealthy neighborhoods leverage these rules to wall themselves off from poorer residents. When states intervened, these effects were reduced.

Brown’s rules would be especially felt in Los Angeles and San Francisco, two cities with significant local development restrictions. Whether they will survive California’s legislative process is uncertain, especially as more residents become aware of how Brown’s plan could restrict their input on what gets built in their neighborhoods.

A successful push could have implications beyond California. Throughout the US and other advanced economies, the rising cost of housing is eating into economic growth and increasing inequality. One study found that if development rules in New York, San Francisco and San Jose had met the national median from 1964 to 2009, the US economy would have been 9.5% larger because more people could have afforded to live in these high-productivity areas.