“Why are you still talking about Tiananmen?”

Hong Kong

Hong Kong

When George Orwell wrote “All propaganda is lies” in his journal in 1942, he did not mention its second most startling characteristic: how incredibly successful propaganda can be.

Take Chinese propaganda: modern, highly digital, even funky, and ever harder to detect, it has had the ability to sink deep into people’s consciousness. On some of the most controversial topics in contemporary Chinese politics, it has gone a long way: Many young Chinese today see Tibet, Tiananmen, Taiwan, the legitimacy of the Communist Party, or Chinese sovereignty over the South China Seas exactly as Beijing would wish.

“Why are you still talking about Tiananmen? China has become prosperous now,” a young Chinese student told me in Beijing last November. At Columbia University during a 2013 talk on Tibetan art, a bright student of international affairs from Wuhan looked at me seriously in the eyes as she said: “People are happy in Tibet. The Chinese government has been spending billions for its development. But we all know that America wants to invade it to weaken China, which is why they spread lies about human rights.”

At Yale University, as I was chatting with some Chinese students in the Sterling Memorial Library coffee shop in 2014, I realized that simply saying that I was a student in Beijing in 1989 made some of them uncomfortable. “Interesting year!” one said. “China has changed a lot since then,” added another unprompted, as the conversation cooled down significantly.

And here in Hong Kong, just a few weeks ago, a Shanghai acquaintance in her forties, often ready to criticize the local government, was visibly irritated when I pointed out a poster in the street advertising the annual march in remembrance of the dead of June 4 by the Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Democratic Movements in China (also called simply “the Alliance“).

“Are you going?” I asked.

She looked offended: “Of course not! Why go on about this? They only do it to annoy the Beijing government anyway,” she said.

In countless conversations with Chinese citizens, in one country or another, the message has often been the same: China would not have been so prosperous had the student demonstrators who occupied Tiananmen Square in 1989 “won.”

So in Hong Kong, as the 27th anniversary of the bloody military crackdown that put an end to the 1989 protests approaches, the battle against propaganda becomes ever more complex. The violent end to the demonstrations in and around Tiananmen, normally referred to as “June 4,” is yearly commemorated in the city’s Victoria Park. The candle-lit vigil is attended by tens of thousands, in spite of the often inclement weather.

In 1989 nearly everybody in Hong Kong was on the side of the demonstrators. Hundreds of thousands of people took to the streets in their support, and the students in Beijing received donations of tents, food, and money. Some have even called the Tiananmen massacre “Hong Kong’s political awakening.”

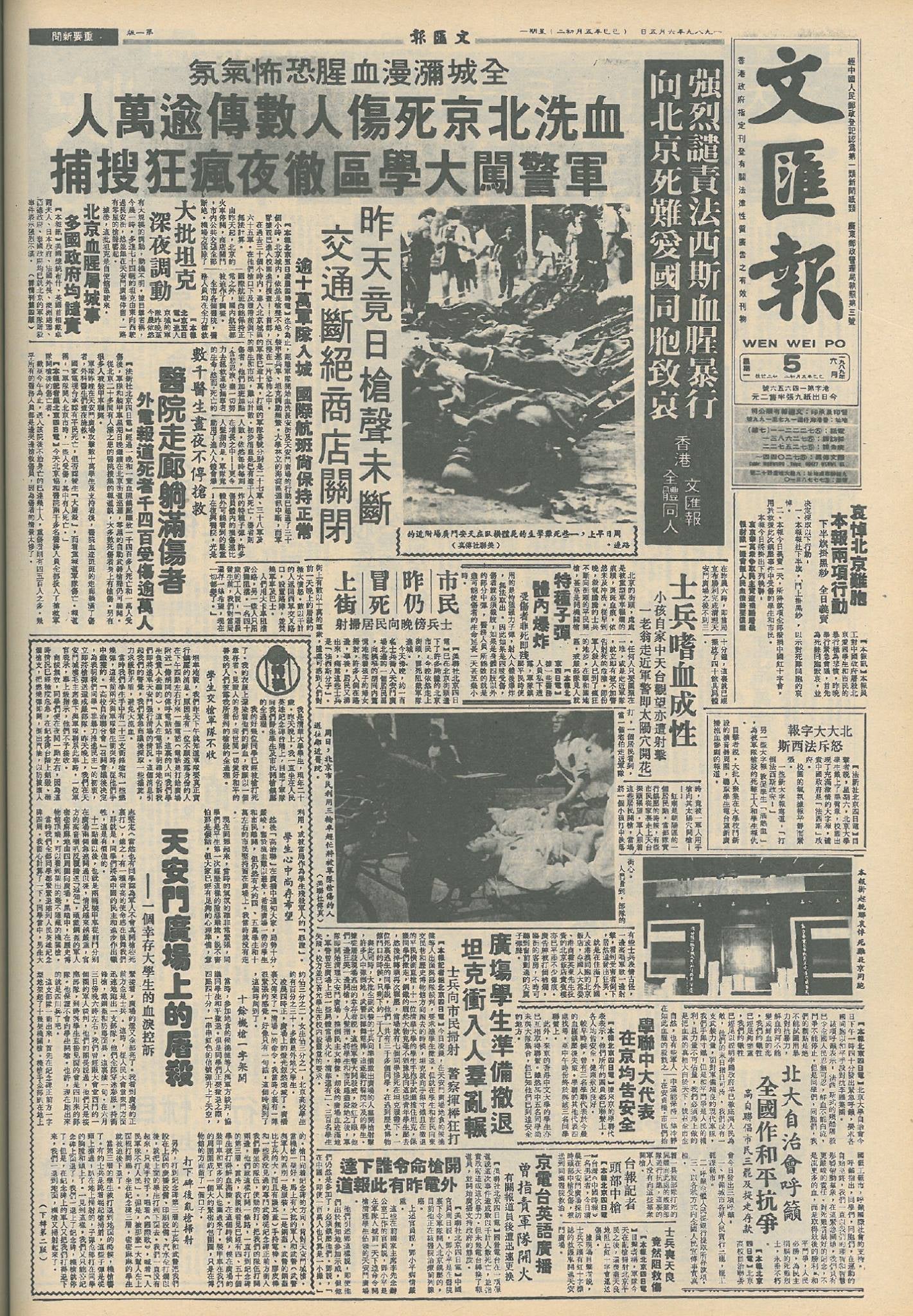

On the mornings of June 4 and 5 of that year—after the tanks had rolled into the square killing hundreds, if not thousands, of citizens—every Hong Kong newspaper, including the pro-China ones, reported the news with shocked condemnations. Close to a million people marched in protest in spite of a violent typhoon hitting the city.

And through these 27 years, Hong Kong has remained the only place on Chinese soil where the events of 1989 are openly discussed, addressed, commemorated, and condemned, while in the rest of the country the few who risk doing so often employ abstruse puns posted on the internet, in a game of cat-and-mouse with the internet censors.

A sizable number of Chinese from the mainland do come across the border to take part in the vigil (which has meant that the vigil’s organizers sometimes speak Mandarin to the crowd, even if the main event happens in Cantonese).

But in Hong Kong, where local identity feels under siege, this year some are feeling less inclined to take part in the June 4 commemoration. The Hong Kong Federation of Students has parted ways with the Alliance, as more students have started to chafe under the “patriotic” label the Alliance has always given itself.

When many mainland Chinese seem content with their newly acquired wealth and the censorship the government has been imposing, small wonder the very idea of fighting for Chinese democracy in Hong Kong feels like a waste of time.