Uber and Airbnb could reverse America’s decades-long slide into mass cynicism

Today’s young Americans are pretty wary of their fellow citizens. In 2014, just 21% of people in the US born after 1980 said they believed that people could generally be trusted, according to the National Opinion Research Center’s General Social Survey. Just a few decades ago, Americans were much more willing to expect good from others: in 1972, 40% of those under age 34 thought most people were trustworthy.

Today’s young Americans are pretty wary of their fellow citizens. In 2014, just 21% of people in the US born after 1980 said they believed that people could generally be trusted, according to the National Opinion Research Center’s General Social Survey. Just a few decades ago, Americans were much more willing to expect good from others: in 1972, 40% of those under age 34 thought most people were trustworthy.

Against this backdrop, the dramatic rise of the sharing economy may seem puzzling. If young Americans are generally mistrustful of others, why are they so confident in the good intentions of their hosts on Airbnb?

The answer, as I explain in my new book, The Sharing Economy, lies with the changing way that we build trust in the digital age.

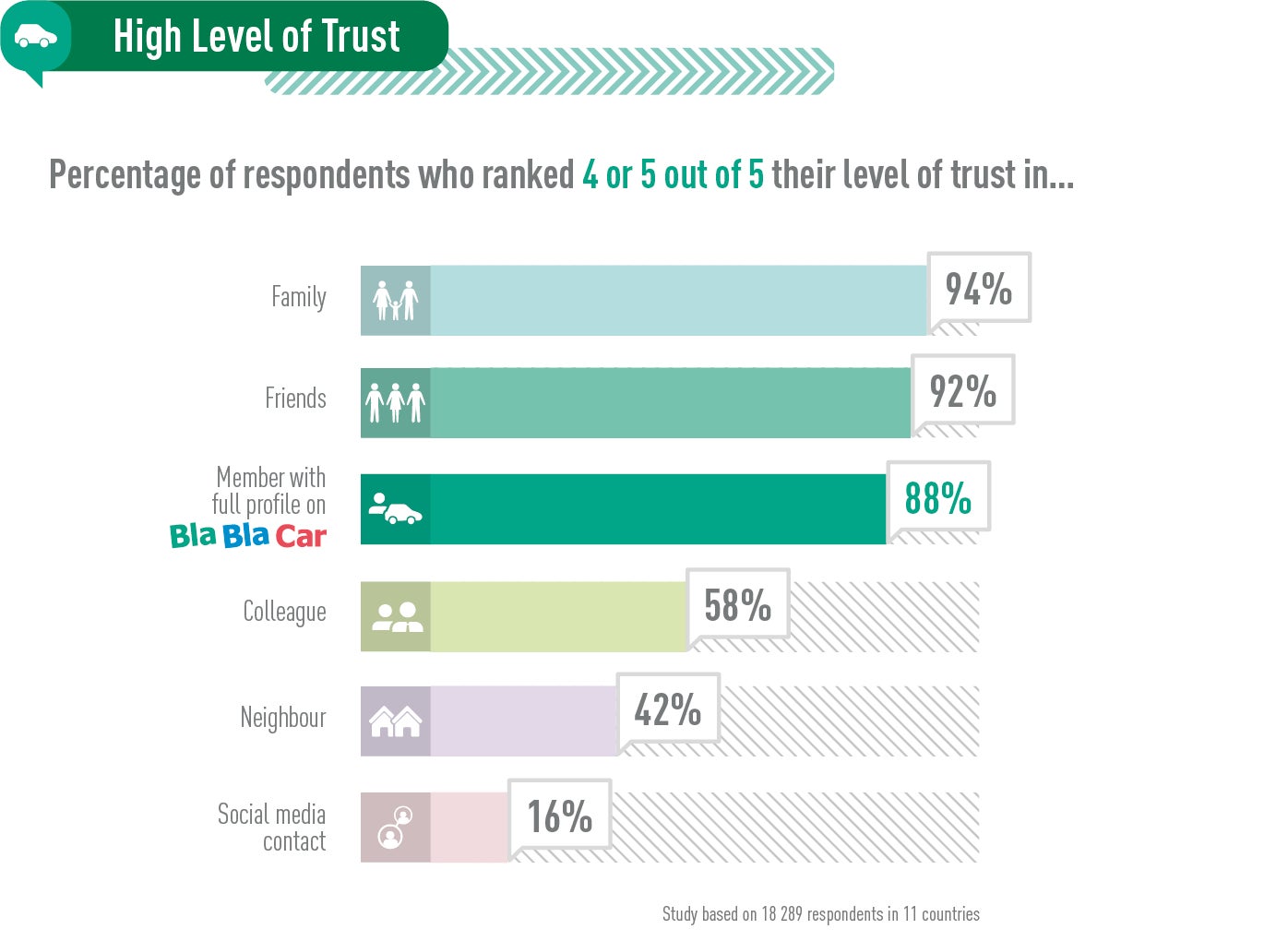

Over the last year, I have studied trust in the sharing economy in collaboration with BlaBlaCar, a city-to-city ridesharing platform that operates in 22 countries and transports more people every day than Amtrak. Last year, we conducted a survey of 18,289 users across France, Germany and nine other European countries. Our goal was to determine how a complete digital profile—including a picture, a brief bio, user ratings from others, some social media validation, and perhaps a verified mobile number—affected the amount of trust users put in their peers.

Our study found that BlaBlaCar users trusted their peers on the platform who they otherwise didn’t know but who had a complete digital trust profile significantly more than they trusted their colleagues and neighbors, and at levels almost comparable to the trust they placed in friends and family. This assessment is especially striking because the safety stakes are quite high in this context. Users are getting into the cars of people they don’t know and saying, “Drive me to another city.”

What forms the basis for these and other leaps of faith taken by millions of people around the world as they commute via Lyft and Uber, lend their homes on Airbnb, or rent their cars to one another using Getaround and Turo? Well, peeling back the layers of these seemingly superficial digital trust profiles reveals surprising depth and nuance.

Over the last two decades, we have become accustomed to learning to trust based on the digital experiences of others. Consider the kind of online reviews popularized by eBay. Most people find that they can accurately assess the reliability of the person selling a used pair of boots or a vintage dresser by relying on the accounts of other people the seller has done business with. Our doubts are further assuaged by the fact that sellers and service providers will know that a subpar performance will result in a bad review or a lower numerical rating.

More recently, we have augmented these online repositories of user experience by digitizing the details of our everyday interpersonal relationships and storing them on Facebook and LinkedIn. These platforms now contain comprehensive, digitized representations of our social capital in the physical world. The more important of these connections are real relationships: our friends, colleagues, classmates and family members. When an Airbnb user is able to access a stranger’s networks of real-world connections, the user gains powerful cues as to others’ authenticity, intent and dependability.

Some sharing economy platforms go further to establish that their users are real and accountable. An Airbnb user can add a verified, government-issued ID to their profile with a system that uses a webcam to validate the ID’s legitimacy. A BlaBlaCar user can similarly assert authenticity by providing a mobile phone number whose issuance was contingent on identity verification. Lyft and Uber conduct a wide range of background checks, in-person screenings and vehicle inspections.

Today’s millennials have been raised with Amazon ratings and Yelp reviews. So it’s little wonder they feel a greater sense of comfort from this digital infrastructure. In fact, this generation’s enthusiastic embrace of the sharing economy may have well been fueled by the way new startups harnessed digital trust, tacitly rejecting the factors that built interpersonal confidence in the past.

Before the 20th century, most people’s economic and social dealings were conducted primarily with fellow residents of their villages or towns. Residents exchanged reputational information with one another as a natural by-product of everyday interaction, so everyone knew which dressmaker had perfect stitches and which tinsmith tended to run late.

Over time, commerce was freed from the confines of local communities. Government rules about food quality allowed people to feel they could trust the eggs and vegetables from farmers they didn’t know personally. Property rights made exchange with strangers a lot less uncertain. Contracts and courts dramatically expanded the options for trade. And today, the combination of corporate brands and government regulation creates sufficient trust in myriad everyday products and services, from the milk we buy to the roller coasters we allow our children to ride. (There’s a reason people feel safer taking their kids to Six Flags rather than the no-name amusement park just off the highway.)

So the sharing economy seems to be returning us to our earlier, community-based forms of trust. Except that rather than relying on our village brethren, we rely on a more extensive digital community of peers.

This faith in digital trust is not misplaced. But it is essential that we remain vigilant until we understand its limits more completely. Although they are powerful, the trust systems of the sharing economy are not foolproof. A summary of user-generated ratings on Uber will never be a perfect predictor of a person’s criminal proclivities. Nor should we ever expect it to be a complete substitute for government oversight.

However, the role of such oversight must evolve. For example, rather than screening individual Uber drivers, city officials might instead mandate more transparent rating systems or more stringent platform-conducted background checks. Forward-looking governments might even partner with platforms, using their troves of data and computer science talent to create delegated systems that can enforce existing laws. For example, New York City yellow cabs allegedly have a history of discrimination against passengers of particular ethnicities. By using the kind of algorithms that credit companies use to flag potentially fraudulent activity, Uber and Lyft might now use digital data trails to assess whether a driver’s passenger histories reflects possible discriminatory behavior.

We should feel buoyed by the fact that a vast majority of sharing economy transactions are safe and positive experiences. And as we use them more and more to fulfill our everyday needs, this pattern of consistently positive interactions with strangers may well prompt us to reconsider our world-weariness, allowing us instead to rebuild our faith in the kindness of strangers. Over time, this may become the true gift of the sharing economy.