The magic of practice, repetition, and “dumb focus”

Every time I get in the pool to swim laps, I make a little underwater noise when I first submerge. I sit on the edge, plop in feet-first, and bend my knees to submerge my butt, shoulders, head, all at once. Then, I push off the wall with my feet and exude a high-pitched hum of bubbles, before my head emerges and I start my exercise. It’s one-part response to the cool shock of being underwater (brrrrrr), one-part glee that I’ve actually made it into the pool (wheeeee).

Every time I get in the pool to swim laps, I make a little underwater noise when I first submerge. I sit on the edge, plop in feet-first, and bend my knees to submerge my butt, shoulders, head, all at once. Then, I push off the wall with my feet and exude a high-pitched hum of bubbles, before my head emerges and I start my exercise. It’s one-part response to the cool shock of being underwater (brrrrrr), one-part glee that I’ve actually made it into the pool (wheeeee).

I never thought this about until I read Swimming Studies, a 2012 memoir by the New York City-based writer and artist Leanne Shapton, which was released in paperback May 24—just in time to be my first beach read of the summer.

Shapton, who swam competitively as a kid and made it to the Olympic trials as a teenager, deftly documents how her athletic training shaped her as an artist and a person. It’s no secret, of course, that practice, practice, practice results in good work. But what makes Swimming Studies such a revelatory read is how Shapton shines a light on the strange, intimate observations a person can make when they’re alone in that space.

“Artistic discipline and athletic discipline are kissing cousins,” she writes. “They require the same thing, an unspecial practice: tedious and pitch-black invisible, private as guts, but always sacred.”

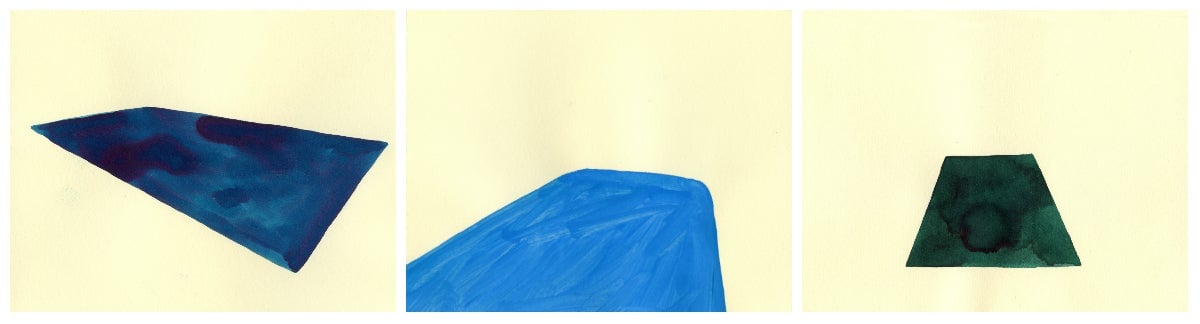

It was only after I’d finished the book, which I steadily devoured over three days lying in the sand, that I realized I had just spent my vacation reading a book about discipline. I wasn’t seeking self-improvement; I just kept turning the pages because her observations—casually delivered in words and watercolors, but razor sharp—make for such evocative pictures.

She transports the reader to 4:25 am in the Canadian winter of 1987, to wake for swim practice and watch a teenage Shapton set the microwave timer for 1:11—the time she aspired to swim the 100-meter breast-stroke in—and complete the race in her mind, eyes squeezed shut, while her muffin-in-mug cooks into a warm, battery mass.

One doesn’t need to be an athlete to understand a longing to be greater than one is—a better writer, a better parent, a better cook. Swimming Studies shows how that longing, and the practice and study it inspires, can shape a person. Practice is magic, she shows. But you’ve got to get yourself to the pool.

“After twenty years, I still search for the dumb focus I had as a competitive swimmer,” she writes. “My fingers used to be pruney, from being in water. Now they’re ink-stained. I replace my laps with stacks of sketches, and my teenage dread of workout with my adult dread of bad work. I fill sketchbooks with repetitive studies, happy only when the last page is finished and I can look back, pick out the handful of good pieces.”

Whether Shapton is quoting David Mamet on directing, Jaws author Peter Benchley on writing, or pianist Glenn Gould on recording, she comes back again and again to the intimate, mindless, time-collapsing role of practice, practice, practice: that weird, wonderful place where a person makes a sound somewhere between brrrrr and wheeee that no one else can hear.