A Texas pollster explains how Hillary Clinton just might turn the Lone Star state blue

Thanks in large part to Donald Trump, a number of solidly Republican states could be up for grabs during the 2016 presidential election. (In US political shorthand, that means turning “red” Republican states to Democratic “blue” ones.)

Thanks in large part to Donald Trump, a number of solidly Republican states could be up for grabs during the 2016 presidential election. (In US political shorthand, that means turning “red” Republican states to Democratic “blue” ones.)

Purplish states like North Carolina and Indiana, which went for Obama in 2008 and Romney in 2012, are once again in the mix, but so are historically solidly-red Arizona and Georgia, which have large Latino and African-American populations, respectively. Presumptive Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton polls massively better with both groups when compared with Trump.

A few pundits have even raised the notion of a Clinton victory in Texas—a huge state with more Electoral College votes than any state other than California.

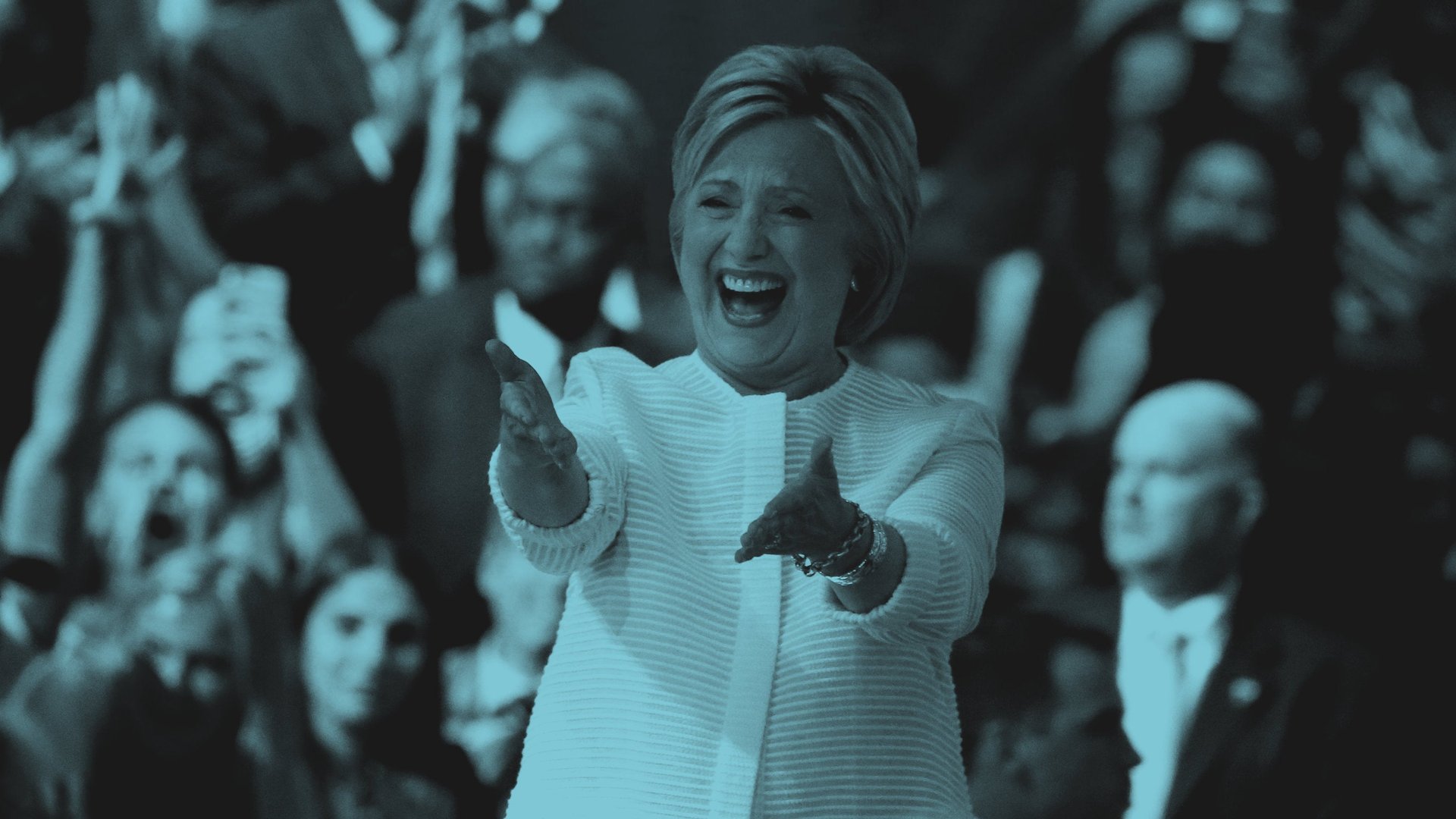

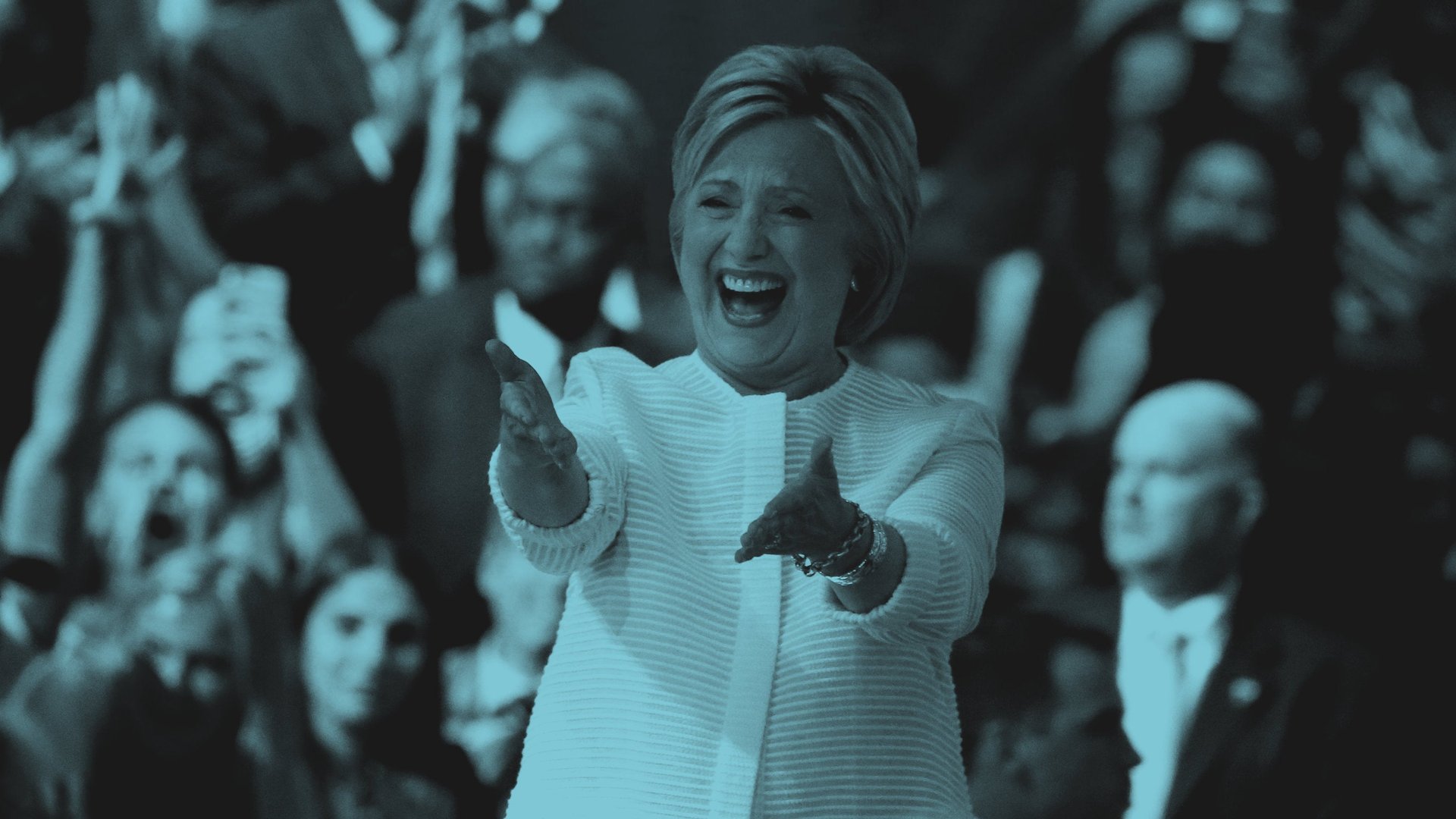

In a lengthy profile by New York magazine’s Rebecca Traister, Clinton was almost salivating at the notion:

“Texas!” she exclaimed, eyes wide, as if daring me to question this, which I did. “You are not going to win Texas,” I said. She smiled, undaunted. “If black and Latino voters come out and vote, we could win Texas,” she told me firmly, practically licking her lips.

A Clinton victory in Texas would mean Democrats could hypothetically lose in all three major battleground states—Florida, Ohio, and Pennsylvania—and still take the White House. But consider Clinton’s massive primary victory in the state, and Trump’s lopsided loss to Ted Cruz in the state’s primary.

There is also Texas’s large and growing Latino population. Clinton won 70% of the Texan Latino vote over Bernie Sanders according to exit polls from the Feb. 2016 primary; whereas more than 80% of Latinos nationwide view Donald Trump unfavorably.

That said, experts are skeptical as to how much, if at all, the dial will move leftward for Texas in November. “Party identification for Latinos in Texas is not as one-sided as it is elsewhere,” Dr. James Henson, a professor of government at the University of Texas, Austin, and director of the school’s Texas Politics Project, tells Quartz. “While Latinos are still overwhelmingly Democratic in Texas, the margins are smaller than in comparable states.”

Still, Henson admits the time might be ripe for a leftward shift in the Lone Star State. “If ever you’re going to swing for the fences, or think that there might be a real outlier outcome, this would probably be that election,” he says, noting Trump’s pronounced unpopularity among mainstream Republicans.

“Secretary Clinton is right,” he adds, “If Latinos and African Americans do turn out in sufficient numbers, she might be able to pull off an upset in Texas.”

Historically, minority turnout in Texas is several points lower than in comparable states—particularly with regards to Latinos. Although they’re the largest minority in Texas by far, turnout is far lower than for white and black Texans. “And there’s not significant upward trend there that we would see driving a big change in 2016,” Henson says.

Neither does Henson see much potential for Clinton to win over more moderate Texan Republicans. “There’s not a lot of potential for crossover,” he says. “Trump and Clinton have very high negatives. Those negatives mostly sort out on a partisan basis.” In other words, most Texan Republicans disgusted with Trump are likely to hold their noses and vote for him anyway.

Or they’ll stay home on election day. Henson says a dip in Republican turnout would certainly boost Clinton’s chances, “but it’s hard to see that being significant enough to turn the tide, given what we know about voting trends.”

Henson’s skepticism, which seems to be shared by number of other political observers in Texas, might have roots in the failed 2014 gubernatorial campaign of Wendy Davis. The state senator, who rose to national prominence when she filibustered a restrictive anti-abortion bill for 11 hours, lost spectacularly to incombent Greg Abbott by a 59%-38% margin.

This time around, Texan Democrats are treading more cautiously. “Democrats have been looking for demographic change in Texas, but we’re hearing less about that than we did with Wendy Davis,” Henson says. “People are being more measured in their predictions, and thinking more about the long term.”

Clinton’s relative popularity in Texas might be better suited to making inroads for a reelection campaign in 2020, or successor Democratic nominee in 2024. Or, Henson notes, “even the 2018 midterm elections, if you ask the optimists.”