This is what it’s like to fast for 20 hours

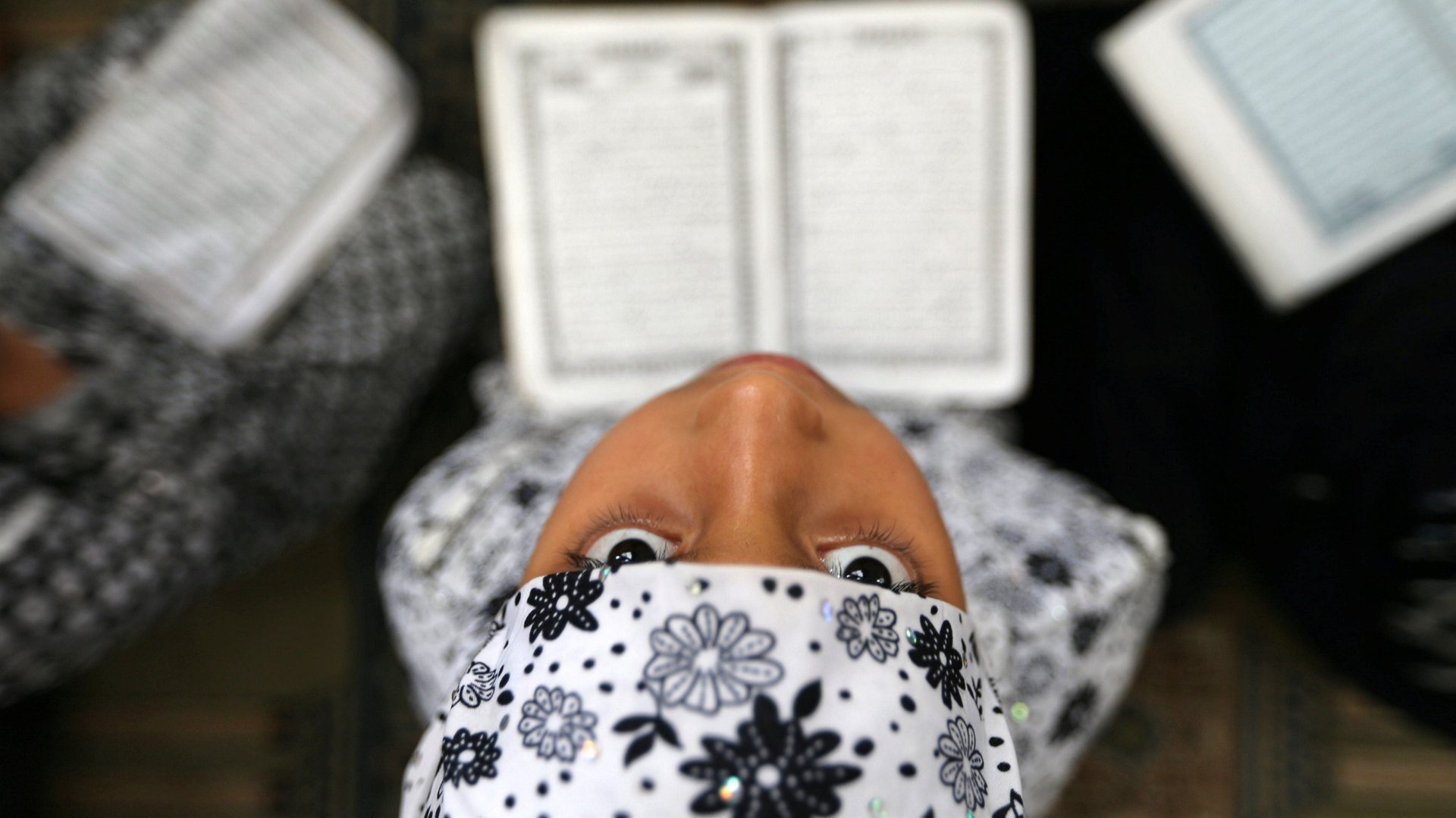

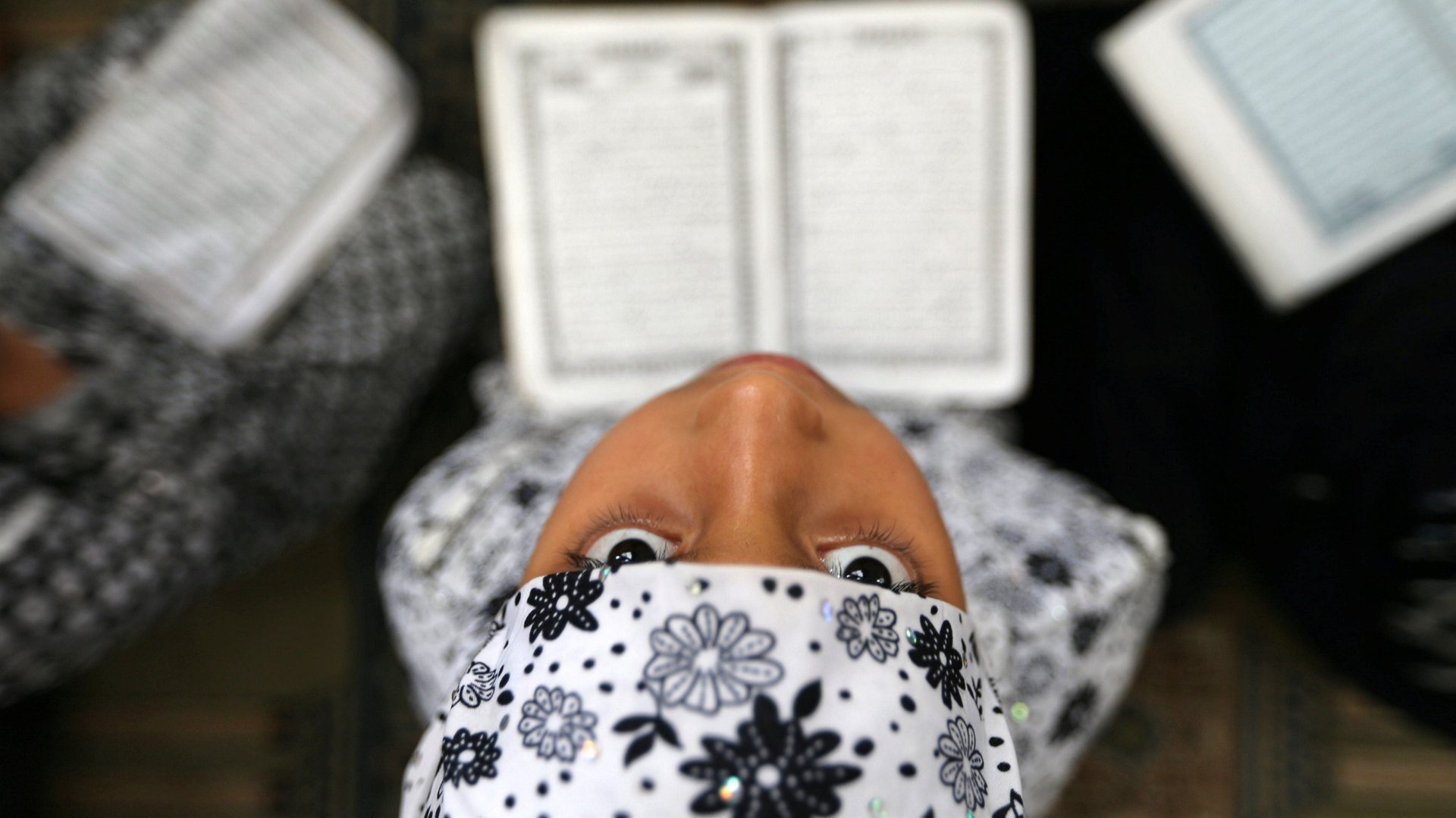

Ramadan is a challenging month for Muslims, who are expected to abstain from food and water from dawn to dusk.

Ramadan is a challenging month for Muslims, who are expected to abstain from food and water from dawn to dusk.

This year, the ninth month of the Islamic calendar coincides with the summer solstice. As a result, Muslims in the northern hemisphere are fasting on the longest days of the year. In Britain, some Muslims are facing a 19-hour fast; it’s the longest, most challenging Ramadan in over 30 years. For Muslims in Nordic countries, it’s even worse. In Stockholm, the day goes on for 20.5 hours. Compare that to the other side of the world—daylight only lasts 11 hours in Auckland and Buenos Aires.

When 26-year-old Yasmeen Alhabbash first moved from Gaza—to Oslo, some 2,250 miles (3,620 km) further north— she told ask friends back home: “Can you believe I am fasting 21 hours here?”

Fasting in Norway is a big jump from the 14 hours she was used to in Gaza. Alhabbash begins her day at around 2 am, where she eats suhoor (the pre-dawn meal) and gives the dawn prayer. She then has to wait until 10.40 pm to eat again. She counts herself lucky as she’s not fasting in northern Norway, where the sun never really sets.

“I sometimes get headaches, feel weak, and it can be hard to concentrate,” Alhabbash tells Quartz. But it’s not the physical toll of Ramadan that’s most difficult for Alhabbash; after being there for seven years, she’s eventually gotten used to the long days. It’s the dramatic change in atmosphere.

It’s during this holy month that she’s most homesick. In Gaza, there’s no escaping Ramadan, which flourishes at every home and street corner, but in Norway, it was an entirely private affair. There’s no booming call to prayer, no large group of family and friends to go to the mosque and break her fast with. “You cannot feel the beauty of Ramadan here,” Alhabbash says.

‘A psychological battle’

That was also initially true for 27-year-old Lukumanu Iddrisu, who moved to Finland from Ghana in 2014. During his first Ramadan in Vaasa, on the west coast of Finland, Iddrisu was alone.

Iddrisu would get up early in the morning for suhoor and then pray. He’d get back to sleep at 3 am, and on some mornings, would have to get back up at 6am for work. After getting home, he would nap if he was particularly exhausted that day, before getting up again, cooking for himself and breaking his fast.

“I did everything by myself in solitude and then I would wake up and pray,” he says. “It was very lonely.” It wasn’t until he decided to go to the local mosque to break his fast that he eventually felt the “togetherness” of Ramadan. In the mosque, he ate and prayed with other Muslims— Sudanese, Albanian, and Somalis, who quickly became his close friends.

While the hours may be longer in Nordic countries, Aamir Sohail, a 35-year-old digital-marketing consultant living in Copenhagen, insists there are some advantages too.

“It’s quite hot in Pakistan and people fasting usually feel thirsty during the day,” Sohail says of his country of origin. “The weather here is much cooler, which in some ways compensates for the time.”

The most challenging part of the fast, Sohail says, is finding the time to sleep, between waking up early in the morning to waiting late into the night to eat. Sohail, who’s been fasting this long for the more than 10 years he has spent in Scandinavia, describes it “a psychological battle” that can easily be won.

Back in Finland, Iddrisu is often asked how he survives, especially with his physically demanding cleaning job waxing and polishing floors throughout the day. Iddrisu now welcomes the challenge of fasting longer and has found out he can withstand a lot more than he once thought. He says he feels closer to God.