The medical industry is plundering a 450-million-year old species for its rare blue blood

The horseshoe crab is a hardy sea creature. It has lived through all the mass extinctions our planet has seen, including the one that killed the dinosaurs, and the biggest one, which wiped out more than 95% of marine species. It has done all that without changing much in the last 450 million years. The crab’s remarkable evolution, or lack thereof, puts it in the small number of species called “living fossils,” because their current forms resemble their oldest fossils.

The horseshoe crab is a hardy sea creature. It has lived through all the mass extinctions our planet has seen, including the one that killed the dinosaurs, and the biggest one, which wiped out more than 95% of marine species. It has done all that without changing much in the last 450 million years. The crab’s remarkable evolution, or lack thereof, puts it in the small number of species called “living fossils,” because their current forms resemble their oldest fossils.

But the hardy crab hasn’t fared so well during the ascent of mankind. In the last two decades, its population has been steadily falling. In some parts of the world, climate change is making its habitat in the sea unlivable. In other parts, the medical industry is harvesting the crab’s unique blue blood.

The crab’s blue blood contains a chemical called limulus amebocyte lysate (LAL), which thickens when it comes in contact with toxins produced by bacteria that can cause life-threatening conditions in humans. Labs use LAL to test its equipment, implants, and other devices for these toxins.

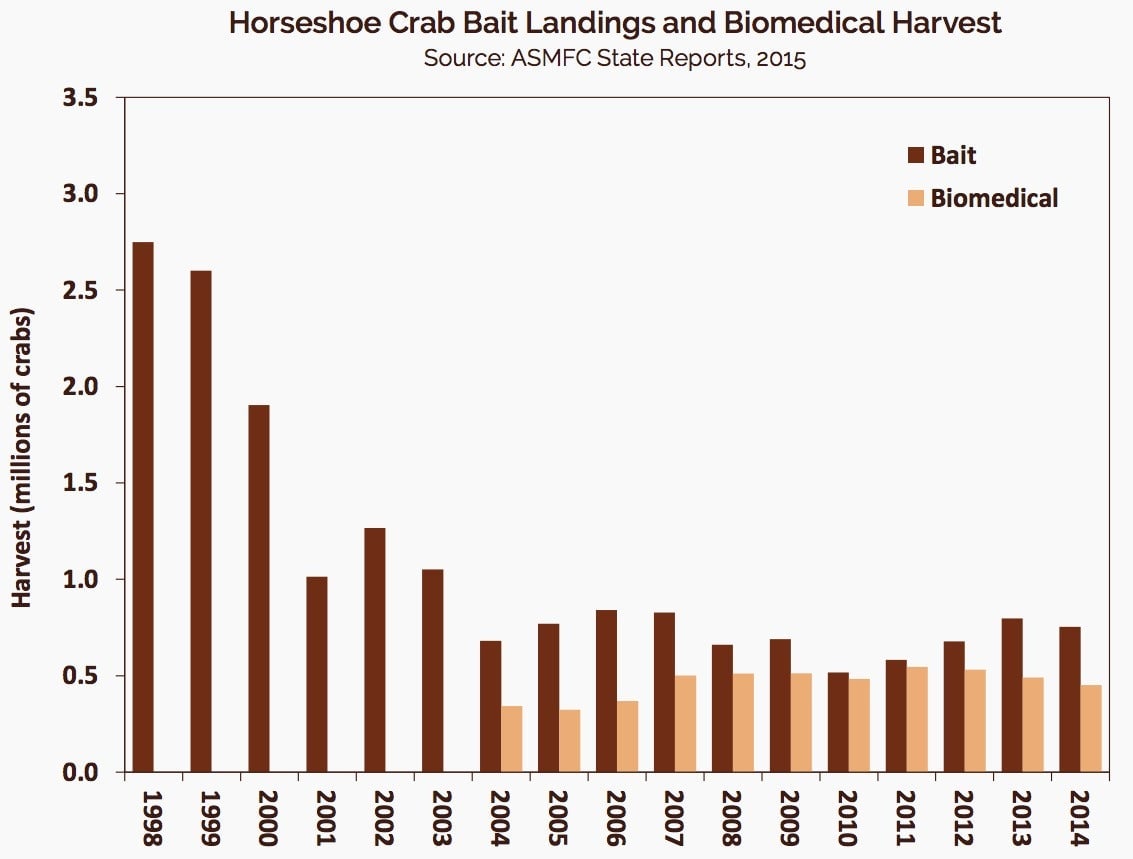

Though the industry claims to harvest with a conscience, it’s estimated that nearly a third of all the crabs who give their blood to save human lives die at sea prematurely. The trend shows up in the falling number of crab landings on US shores.

Though many companies are trying to create a synthetic equivalent of the chemical, none have fully succeeded yet. This means, for now, the medical industry relies on bleeding these arthropods for the life-saving LAL.

The LAL recovered from the crab’s blue blood is valuable stuff. It’s estimated that a liter of LAL can cost as much as $15,000. So it’s no wonder that the number of crabs harvested has nearly doubled since 2004.

In theory, if the bleeding is done properly, the crab should recover when released back into the sea. The trouble is, according to an investigation by Scientific American, scientists have a poor understanding of how many crabs actually survive the bloodletting. The industry estimates that 4% of the crabs die because of the bleeding, but scientists say it could be as high as 40%. Studies being done this year are seeking a more definitive answer, but it’s likely that the eventual number will be at the higher end of that range.

The crab bleeding industry is not regulated, partly because it was thought that bleeding doesn’t cause too many crabs to die. Because the industry is not bound to release any estimates of how many crabs it bleeds, it is unclear just how severe the problem is. And while the industry says that it only harvests 30% of the blood in any single crab, there is no oversight to ensure more blood isn’t drawn.

Even if the industry’s estimates are correct, preliminary studies show that removing 30% of crabs’ blood can leave them disoriented and debilitated, reducing female crabs’ ability to spawn, and leading to early death. Along with other factors affecting the population of horseshoe crabs, some scientists are petitioning the International Union for Conservation of Nature to move horseshoe crabs on the Red List of Threatened Species from “near threatened” to “vulnerable.” This could help make the case for imposing regulations on the medical industry’s use of horseshoe crabs.

Some species of the horseshoe crab are eaten in Asia, while others are used as bait for bigger fish. Some are dying because of pollution, while others are being driven out of their homes by climate change. These combined threats mean this living fossil may finally be heading towards becoming an actual fossil.