The JOBS Act turns one, and let’s be honest, it’s a failure

On April 5, 2012, in the Rose Garden of the White House, US president Barack Obama signed the Jumpstart Our Business Startups Act, one of those distinctly American pieces of legislation that hits you over the head with an unequivocally positive acronym—in this case, JOBS. The law, parts of which went into effect right away, was intended to help startups grow and, in the process, add more jobs to the US economy. Exactly a year later, it’s worth taking stock of how that’s going.

On April 5, 2012, in the Rose Garden of the White House, US president Barack Obama signed the Jumpstart Our Business Startups Act, one of those distinctly American pieces of legislation that hits you over the head with an unequivocally positive acronym—in this case, JOBS. The law, parts of which went into effect right away, was intended to help startups grow and, in the process, add more jobs to the US economy. Exactly a year later, it’s worth taking stock of how that’s going.

Fewer

small companies are going public

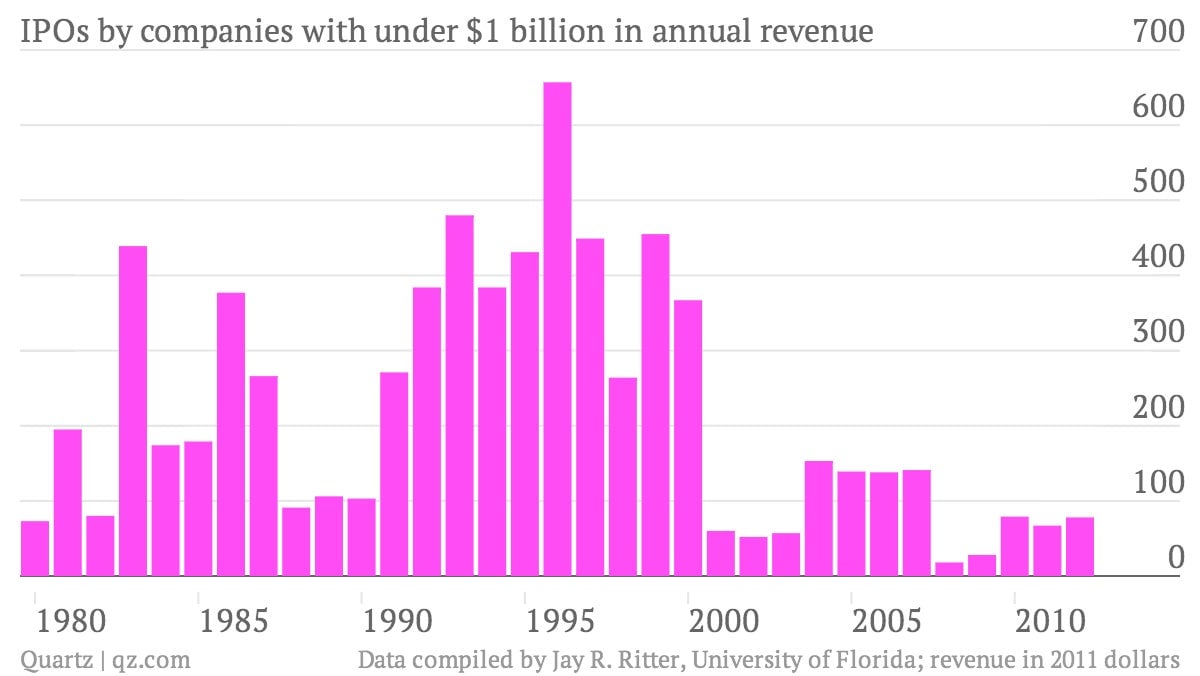

The JOBS Act was supposed to encourage smaller companies to go public. Startups, it was argued, were delaying IPOs or avoiding them altogether because of the regulatory burdens, stunting potential growth in the American economy. So the JOBS Act greatly reduced the disclosure and accounting requirements for IPOs by companies with less than $1 billion in annual revenue.

But in the year since the law went into effect, just 63 such firms have gone public, down from 80 in the previous 12 months. That’s a 21% drop despite improving economic conditions. And in Silicon Valley, at which many provisions of the JOBS Act were explicitly aimed, the situation is even more dire: only eight venture-backed American companies went public in the first quarter of this year, raising $672 million, compared to 19 such IPOs that raised $1.7 billion a year prior, before the law was signed. The dot-com boom this is not.

And why should it be? A glut of startups going public isn’t actually desirable. Instead, it’s clear that IPOs set up perverse incentives that favor short-term profits over sustainable businesses. “For many young companies,” wrote Felix Salmon in a persuasive essay last year, “the drive to go public results in a death spiral of unsustainable growth.” Look, even investment bankers—the ones who take a cut of each inopportune IPO—have soured on the JOBS Act, with just 29% of them calling the law effective and 80% criticizing the lack of transparency among companies going public under the law.

But more companies are avoiding scrutiny

The JOBS Act was originally favored by venture capitalists frustrated by the dearth of IPOs to provide huge returns on their investments. Not incidentally, they wrote the bill.

Key provisions of the JOBS Act were drafted on the kitchen table of Kate Mitchell, a partner at Scale Venture Partners, according to Bloomberg’s definitive reconstruction. In March 2011, then-US Treasury secretary Tim Geithner held a conference titled, “Access to Capital: Fostering Growth and Innovation for Small Companies.” During a break, Mitchell ducked into an empty room with:

- Greg Becker, CEO of Silicon Valley Bank;

- Steven Bochner, partner at Palo Alto law firm Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati;

- Carter Mack, president of San Francisco investment bank JMP Group;

- and others.

They began formulating what would become known as the “regulatory on-ramp” provision of the JOBS Act, which exempts “emerging growth companies” that go public from external audits of their financials for five years—a rollback of the Sarbanes-Oxley accounting reform bill. The unofficial “Mitchell Commission” issued recommendations in October 2011; they became law six months later. “This is probably the only bill I’ll be involved with in my life, but the people who do this for a living say this is shocking how quickly it went through,” Mitchell said shortly after the signing.

There she is in the center of the frame behind president Obama and next to AOL founder (and current venture capitalist) Steve Case, another key figure in lobbying for the bill, and Republican majority leader Eric Cantor, who had been advocating for his party to strengthen its ties with Silicon Valley:

But while JOBS Act hasn’t led to more IPOs, more than 100 companies have taken advantage of the on-ramp provision, which allows them to secretly file papers with federal regulators while exploring the option of going public. I’ve previously raised the possibility that Twitter, which is likely to qualify as an emerging growth company, will file its IPO secretly. Money transfer company Xoom did it; file storage firm Dropbox could, too.

Untold number of startups have also avoided public disclosures that used to be required of any company with more than 500 shareholders, which is what pushed Facebook into the financial limelight; the JOBS Act raised the limit to 2,000 shareholders. That provision was also supported by non-startup companies like convenience-store chain Wawa, a privately held firm that wants to remain that way and keeps its financial information private.

All told, companies are saving money on compliance, but investors know much less about highly speculative investments, and that opacity hasn’t led to the uptick in IPOs it was supposed to produce.

But guess who is going public under the JOBS Act

Oh, just a little emerging-growth company named Goldman Sachs.

The investment bank is creating a new finance company (paywall), Goldman Sachs Liberty Harbor Capital, to invest in the risky but potentially high-yielding debt of small US companies. Taking that new firm public is a way around the Volcker Rule, which will soon prohibit banks from making trades with company funds. But as Goldman noted in a regulatory filing for the new firm: “We are an ’emerging growth company’ within the meaning of the recently enacted Jumpstart Our Business Startups (JOBS) Act,” which means it won’t have to reveal much information until just before the IPO and won’t have to submit to audits for five years.

Goldman isn’t the only company that the JOBS Act’s framers probably didn’t have in mind when they drafted the law. Several “blank check” firms, or shell companies, have filed for IPOs (paywall) under the law. These aren’t job creators; in fact, shell companies typically have zero employees and are used instead to facilitate mergers and acquisitions, often utilizing offshore tax havens. But because they also have little revenue, they qualify as emerging growth companies under the JOBS Act and can avoid lots of regulation.

More fun on the way

There are other provisions of the JOBS Act that haven’t taken effect quite yet, so it’s only fair to reserve judgement. One will allow hedge funds and other private securities to advertise, which calls to mind billboards for SAC Capital—”We’re on the inside track!”—but is more likely to be used by small-time investment vehicles that didn’t previously stand a chance of raising capital. Which might be nice, but it’s only a good thing if those firms are worth investing in.

Another highly anticipated provision will allow startups to “crowdfund” investments from the general public. Again, that could democratize the world of venture capital and allow more great innovation to flourish.

But considering the JOBS Act’s year-one record, will it live up to its promise?