Why Chinese central bank policy—and not speculators—is probably driving the yuan’s strengthening

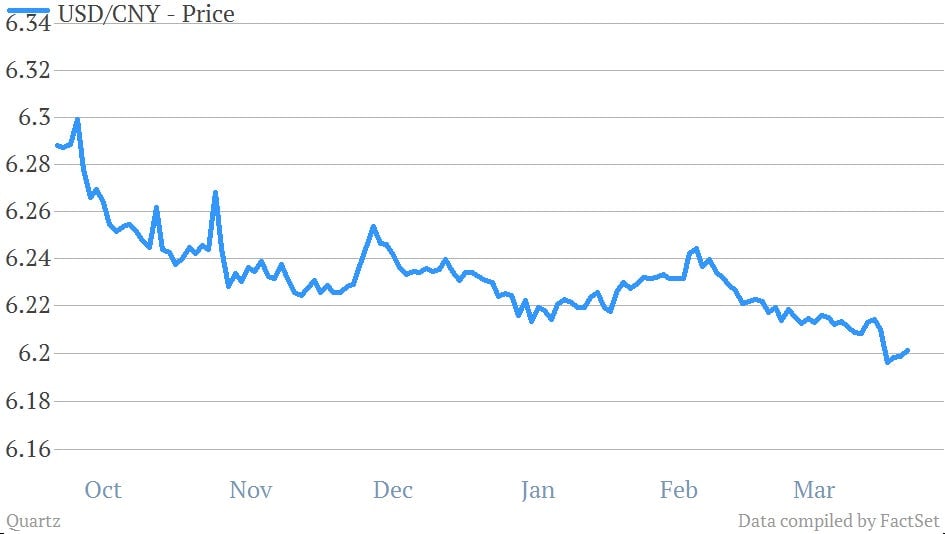

The Chinese yuan got pricier this past week. Starting out at 6.2102 against the dollar, it came to rest at 6.206 before the Chinese currency authorities took off on Thursday on a four-day weekend to sweep tombs:

The Chinese yuan got pricier this past week. Starting out at 6.2102 against the dollar, it came to rest at 6.206 before the Chinese currency authorities took off on Thursday on a four-day weekend to sweep tombs:

It’s clearly part of a more general trend. The government, which sets the narrow band in which it allows the yuan to trade, has let it strengthen 2.9% since last July.

What’s driving this appreciation? Speculative capital, commonly known as “hot money,” is increasingly being cited as a factor. This is likely flowing into the property market, as only certified institutional investors are allowed to invest in Chinese stocks (and it’s not a very inviting market, to boot). And while some of that money is flowing in order to invest in Chinese real estate, other inflows of foreign cash are riding an appreciating yuan and the strengthening economy.

“There’s been an increase in hot-money inflows, but [China’s central bank] may find it difficult to let the yuan rise too fast or tighten monetary conditions too dramatically because the economic recovery remains slower than expected,” Zhu Chaoping, head of research at ChinaScope Financial told the Wall Street Journal (paywall).

If so, that’s not good news. Hot money creates a nasty dilemma (pdf). Inflows are inflationary. But the traditional inflation antidote—raising interest rates—doesn’t help. In fact, it sweetens return, attracting more hot money. Of course, in an open system inflows would strengthen the currency pretty quickly, offsetting those returns. But China’s closed capital account prevents this.

Back in 2007 and 2008, the Chinese government grappled with hundreds of billions—if not trillions—of dollars worth of “hot money.” It never lit on a solution—but the financial crisis made it so that it didn’t have to. Now, likely due to quantitative easing in advanced economies, that prospect may be rising anew.

But while hot money could be the cause of that appreciation, Patrick Chovanec, chief strategist at Silvercrest Asset Management, is skeptical. Capital outflows have indeed moderated, Chovanec tells Quartz, and there’s more capital flowing into China due to “rebounding confidence, whether it’s correctly placed or not.”

A strengthening yuan hints at the People’s Bank of China’s evolving foreign exchange reserve policy more so than it signifies big swings in capital movements, he says.

That’s because China’s foreign exchange reserves aren’t a treasure hoard. The PBOC uses them to manage the yuan’s trading value, accumulating and drawing down its reserves to keep the yuan within a desired trading band. For instance, in order to offset last year’s capital outflow—which would pressure the yuan to weaken—it had to draw down reserves dramatically.

But now capital flows seem to have reversed, putting pressure on the yuan to appreciate—and the PBOC is clearly letting it. What’s that all about?

Priorities, says Silvercrest’s Chovanec. ”Countries can have control over two out of three things. They can control domestic interest rates, they can have free flows of capital internationally, or they can have control over the exchange rate,” he says. “If you are the PBOC and you want to move toward opening the capital account, which is what they say they want to do, and you want to have flexibility on domestic monetary policy, that requires you not to intervene on exchange rate.”

And if it were to intervene to prevent the yuan from appreciating, that would mean building up its foreign exchange reserves once again—which is probably not a terribly attractive prospect given the crummy yields on Treasurys, in which a great deal of the reserves are invested.

But that doesn’t necessarily mean the yuan will continue its aggressive strengthening. ”[The PBOC is] not an independent central bank, so they can push in one direction, but they might be pushed back again,” says Chovanec. “The policy product we see isn’t the [result] of centralized rational decisions.”

In other words, no matter how committed China’s central bankers are to preparing to open up the capital account—or concerned about expanding China’s massive foreign exchange reserves—other political interests, ones that are more powerful than the central bankers, may prevail.