Three takes on the world’s big bet on Chinese reform

The view from Hong Kong

The view from Hong Kong

Ronnie Chan, the billionaire Hong Kong investor, says there is only one comparison for China’s economy over the next decade: The enormous period of US growth between 1890 and 1914, as industrialization and land grabs combined to rocket the country to prosperity.

His audience at the Asian Pacific Business Outlook conference in Los Angeles, largely executives at US companies looking to export goods to Asia, were salivating. But Chan also had a warning.

“The last ten years have been a very sad period of Chinese history,” he said. “China had a great opportunity to launch, if not complete, many of the necessary social reforms. For the past ten years, China basically did nothing in that regard, and they will pay dearly for it.”

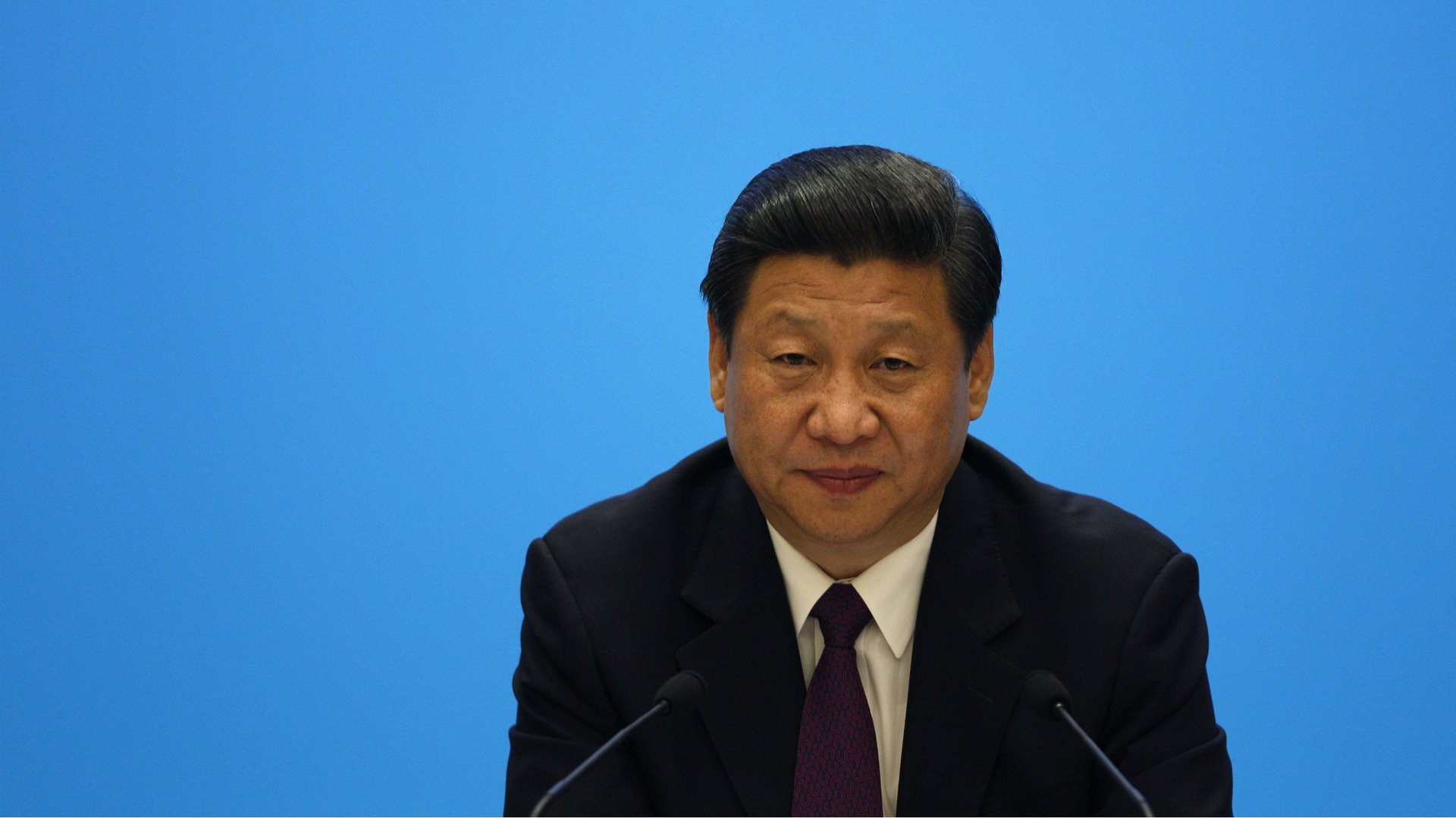

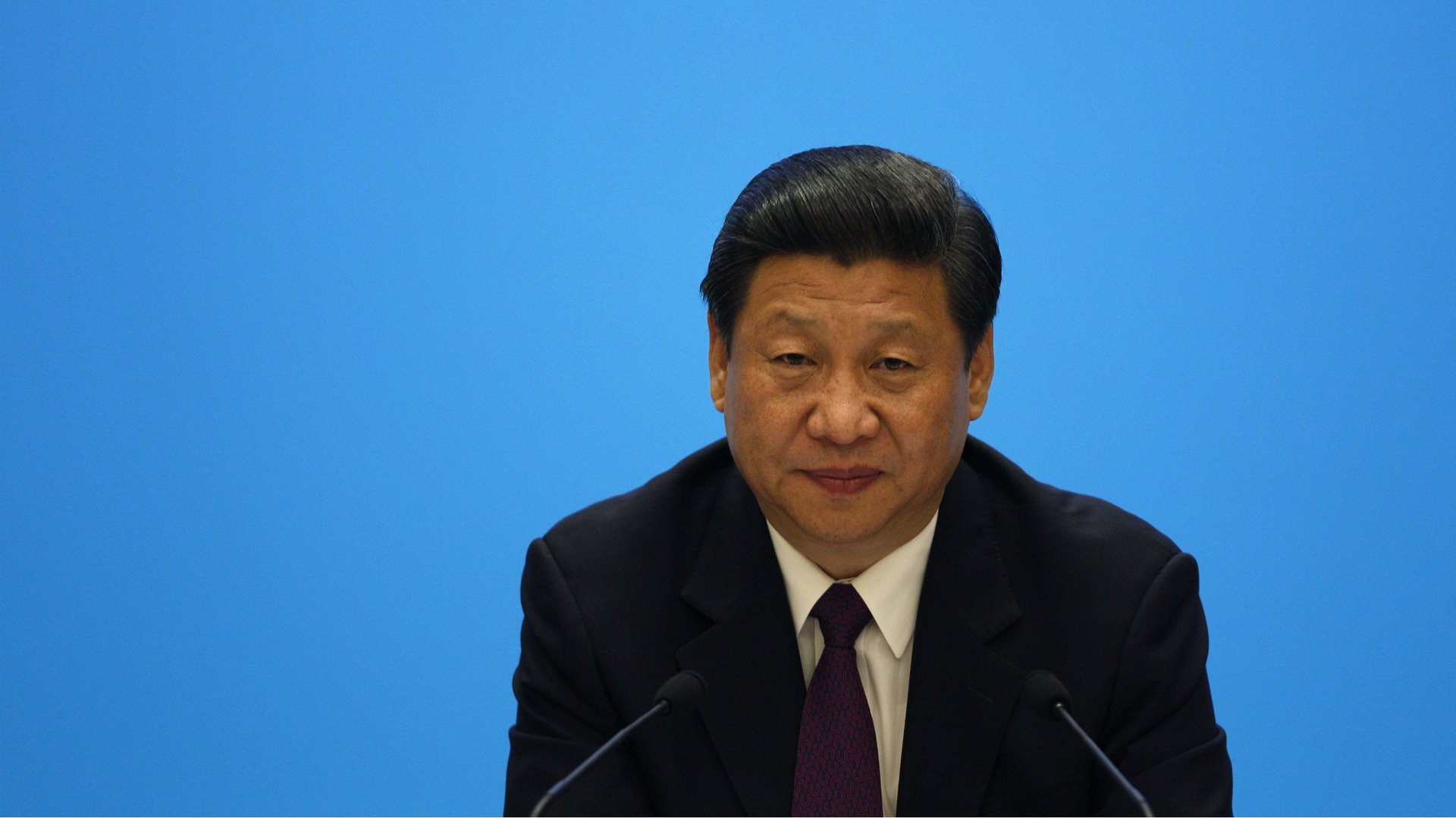

Everyone watching new Chinese President Xi Jingping and his team have wondered how far they will take promises of reform. Most important is support for China’s domestic market and its poorer citizens, which many economists see as necessary to continued stable growth. Chan brought up the recent debate over the wisdom of investing in China between hedge fund short-seller Jim Chanos and Stephen Roach, the former Morgan Stanley Asia economist. While he conceded that social unrest, particularly growing income inequality, could disrupt the Chinese economy (Chanos’ concern), he thinks shorts will miss an enormous opportunity.

“What if social unrest does not happen? You never know when it’s going to happen. If it doesn’t happen in the next ten years, and you short the market, you’re really really in trouble,” Chan says.

But he has one caveat for his $11 billion of shopping mall investments in China—he didn’t borrow any money for them. Nice financing, if you can get it.

The view from the US State Department

Nearly 30 years ago, Richard Drobnick, the director of the University of Southern California’s international business center, helped raise the money for the first APBO. That year, the talk was Japan, then the Asian economic dynamo, with a session nearly every hour of the two day event focused on its economy. Today, it’s China.

You could sense the mood when Dorothy Lutter, the top US commercial diplomat in Mexico, began a discussion by mentioning “the North American Free Trade Agreement between the United States, Mexico and China—whoops, I’ve got China on the brain, must be those speakers this morning.”

William Zarit, the senior commercial diplomat in Beijing, was circumspect in assessing the new leadership team. A key worry is that new vice premiere Zhang Gaoli, a supporter of state-owned business, had been appointed to run most economic policy, replacing the more reform-friendly Wang Qishen. However, Wang’s job in the new government is fighting corruption, and while that may be seen as a demotion, it’s also integral to the reform process and perhaps a sign of the new team’s priorities.

Policy changes around the margins will effect the economy, but the central test is whether Beijing will adhere to a growth plan it endorsed along with the World Bank last year. It recognizes that the ruling communist party needs to have less direct influence on business, even as state-run companies remain the focus of Chinese growth. So Zarit will be watching how much power the new officials concede to the private sector.

The view from Mao’s interpreter

Sidney Rittenberg is one of the most colorful figures in US-Chinese history, a US soldier who became the first American member of China’s communist party and an associate of Mao Zedong, enduring two long prison stints thanks to China’s tumultuous internal politics. Since he returned to the US in 1980, he has worked as a consultant for major companies, including Intel and Levi’s, that are seeking to enter China’s markets.

For Rittenberg, there is no question that China’s new leaders have economic reform in mind, specifically, the change from government-financed growth to growth financed by private markets. Like Chan, however, he believes time is of the essence.

“The party center is still strong enough to be able to break through [opposition from state-owned conglomerates],” he said. “If it’s not done in the next five years, let’s say, it could be a much bigger problem. The tendency has been, one, of lobbying to become much more powerful for the big conglomerates, and two, for the leaders of the private industry and government officials to change places—a kind of government-industrial complex forming.”

Rittenberg recalled a meeting with foreign correspondents in Beijing in 2010. They expected rising party official Bo Xilai to be the next number two in China’s government. Rittenberg bet Australian reporter John Garnau a Peking duck dinner that Xilai, who stepped on too many toes in the party, wouldn’t make it very far, and collected on his bet last June, after Xilai’s dramatic fall from power.

“During the cultural revolution, I remember very well, he was one of the leaders of the worst Red Guard gang in Beijing,” Rittenberg said. At the time, Rittenberg was leading one of those Red Guard gangs himself.