Can a Swedish startup save China’s struggling solar industry?

The next big thing in solar technology could be very, very small. Just how tiny? About .00008 inches (.0002 centimeters).

The next big thing in solar technology could be very, very small. Just how tiny? About .00008 inches (.0002 centimeters).

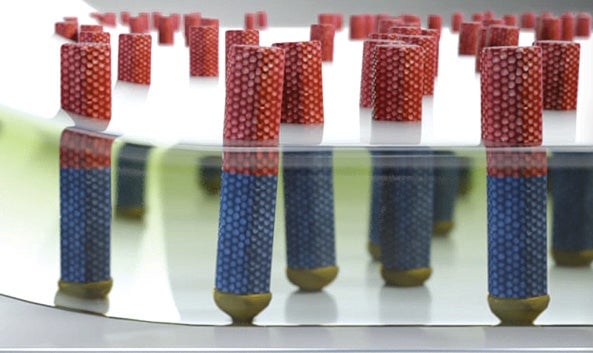

That’s the length of a gallium arsenide nanowire that Swedish startup Sol Voltaics has invented. The company claims a layer of nanowires added to a conventional solar panel can boost its efficiency by as much as 25%.

That could potentially solve a big problem for a debt-burdened Chinese solar industry facing plummeting prices for its solar panels. (China is home to about 80% of the world’s solar panel manufacturing capacity.) Companies like Suntech and Yingli could gain a competitive advantage by selling a higher-efficiency nanowire-enhanced solar panel without incurring the steep capital costs of developing a better photovoltaic module.

“If we can move the efficiency high enough, the Chinese can stabilize their prices or even get better prices for their panels and dig themselves out of their negative margins,” says David Epstein, a veteran Silicon Valley entrepreneur and venture capitalist who moved to Lund, Sweden, to become Sol Voltaics’ chief executive.

That’s a big if. While Sol Voltaics has shown that the technology, dubbed Solink, works in the laboratory it has yet to prove it in commercial production, which is set to begin in 2015.

Still, Sol Voltaics is emblematic of global shifts in the industry as once-promising cutting-edge solar startups in Silicon Valley falter and US venture capitalists lose their appetite for capital-intensive manufacturing.

The venture sprang from founder Lars Samuelson’s nanotechnology research at Sweden’s Lund University. It’s been long known that gallium arsenide is one of the most efficient materials to generate electricity from sunlight. But gallium arsenide is also prohibitively expensive and has been mainly used in satellite solar arrays built by deep-pocketed governments and military contractors.

Lund and his colleagues, however, devised a way to create gallium arsenide nanowires that concentrate sunlight and act as microscopic photovoltaic cells. That means only about a gram of nanowires is needed per square meter of solar panel.

(Innovalight, a Silicon Valley startup that was acquired by DuPont in 2011, makes a silicon ink that boosts solar panel efficiency by around 1%).

Since Sol Voltaics is only selling nanowires and not solar panels it does not need to raise hundreds of millions of dollars to build factories. In fact, a 10-foot by 20-foot (3-meter by 6-meter) machine can make 100 megawatts’ worth of nanowires a year, according to Epstein. That means production can remain in Sweden, making it easier to safeguard the company’s intellectual property.

Capital costs are low as well. Sol Voltaics has raised $11 million from European investors, including Alf Bjørseth, the founder of Norway’s REC Solar, one of the world’s largest solar manufacturing companies.

Epstein says it will cost Sol Voltaics less than $50 million to reach commercial production. But he won’t be returning to Silicon Valley to raise that cash.

“Those traditional VCs in Silicon Valley have already placed their bets and been bitten two or three times,” says Epstein. “European investors are quite bullish on clean tech and Middle East investors are increasingly interested.”