Abenomics will create winners and losers within Japan Inc.

Abenomics, the money printing, yen weakening plan spearheaded by the Bank of Japan at the behest of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, is meant to bring back inflation, which could well be the remedy for two decades of recession that Japan desperately needs. But it will not be equally great for all Japanese companies.

Abenomics, the money printing, yen weakening plan spearheaded by the Bank of Japan at the behest of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, is meant to bring back inflation, which could well be the remedy for two decades of recession that Japan desperately needs. But it will not be equally great for all Japanese companies.

“Companies that cannot pass on the costs of inflation will find things hard,” says Jefferies global equity strategist Sean Darby. “These would be companies in regulated markets that cannot push up prices while, at the same time, their input costs, such as wages, are rising.”

For example, if Abenomics works as planned investors would do well do avoid sectors like electricity, as providers would have to buy oil and gas with a weaker yen but could not charge higher fees because of government price controls.

Here is a brief recap of how Abenomics is supposed to work: The Bank of Japan plans to print $1.43 trillion worth of new yen. And that money printing is meant to cause inflation. This works theoretically because of the relationship between the amount of money in an economic system and the value of goods an economy produces. If economic output stays constant and the money supply increases, there is more money chasing the same number of goods and services, driving prices go up. Put another way, people will have more cash and should be willing to spend more on the same goods. Here is an explainer with more technical detail.

Abenomics should, overall, benefit corporate earnings.

Japan’s big problem since the early 1990s, when a major asset bubble popped, has been deflation.

Since then, the value of land and corporate assets has fallen and failed to recover. Companies were required to constantly write down the value of their assets as values fell, taking chunks (paywall) out of corporate earnings. Deflation has also caused people to delay buying items such as furniture, or even new homes. Companies have postponed investments.

Property developers are set to do well. Inflation should hopefully cause Japanese land prices to rise again. There are already signs this is happening, at least in urban Tokyo, where the sale prices of apartments are now ticking up after years in the doldrums.

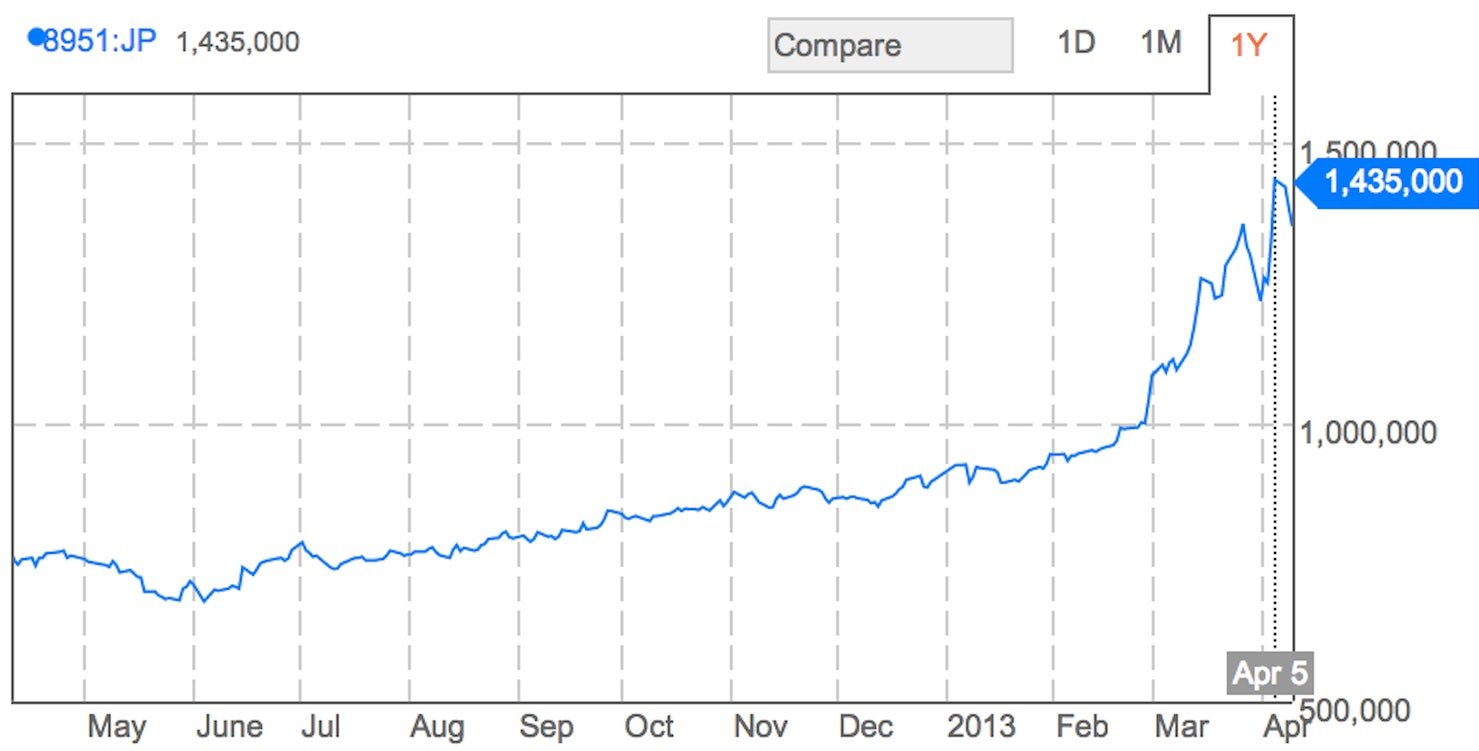

Another reason for cheer in the Japanese property sector is that the Bank of Japan plans to buy more shares in local real estate investment trusts (funds that hold real estate assets). So Japanese property equities have been booming. A case in point: Nippon Building Fund, Japan’s largest so-called J-Reit.

The outlook is much cloudier for energy companies. Take Tokyo Electric Power Company (usually referred to as Tepco). The downtrodden owner of the earthquake-cripped Fukushima nuclear plant lost (pdf) 299 billion yen ($3 billion) in the half year to last September. Its idled nuclear capacity has made it much more reliant on oil, gas and coal imports and its costs of buying fuel (pdf p.4) have ballooned.

The yen has fallen around 17% against the dollar since last September. Consultancy Capital Economics forecasts the Japanese currency could weaken to 120 per dollar in 2014, against approximately 99 to the dollar now. That will be bad news for poor Tepco, which of course has to buy its oil in dollars. To make things worse, oil prices are expected to rise this year. Meanwhile, Abe is aiming for lower electricity prices via deregulation because the high cost of power is a disincentive for businesses to invest in Japan. The nation’s utility providers are set to push back against this plan, arguing they stilll need time to stabilize their businesses following the March 2011 earthquake. The bottom line, however, is that power providers will be among Abenomics’ biggest losers.