What businesses can learn from British Cycling’s 70% rise in female coaches

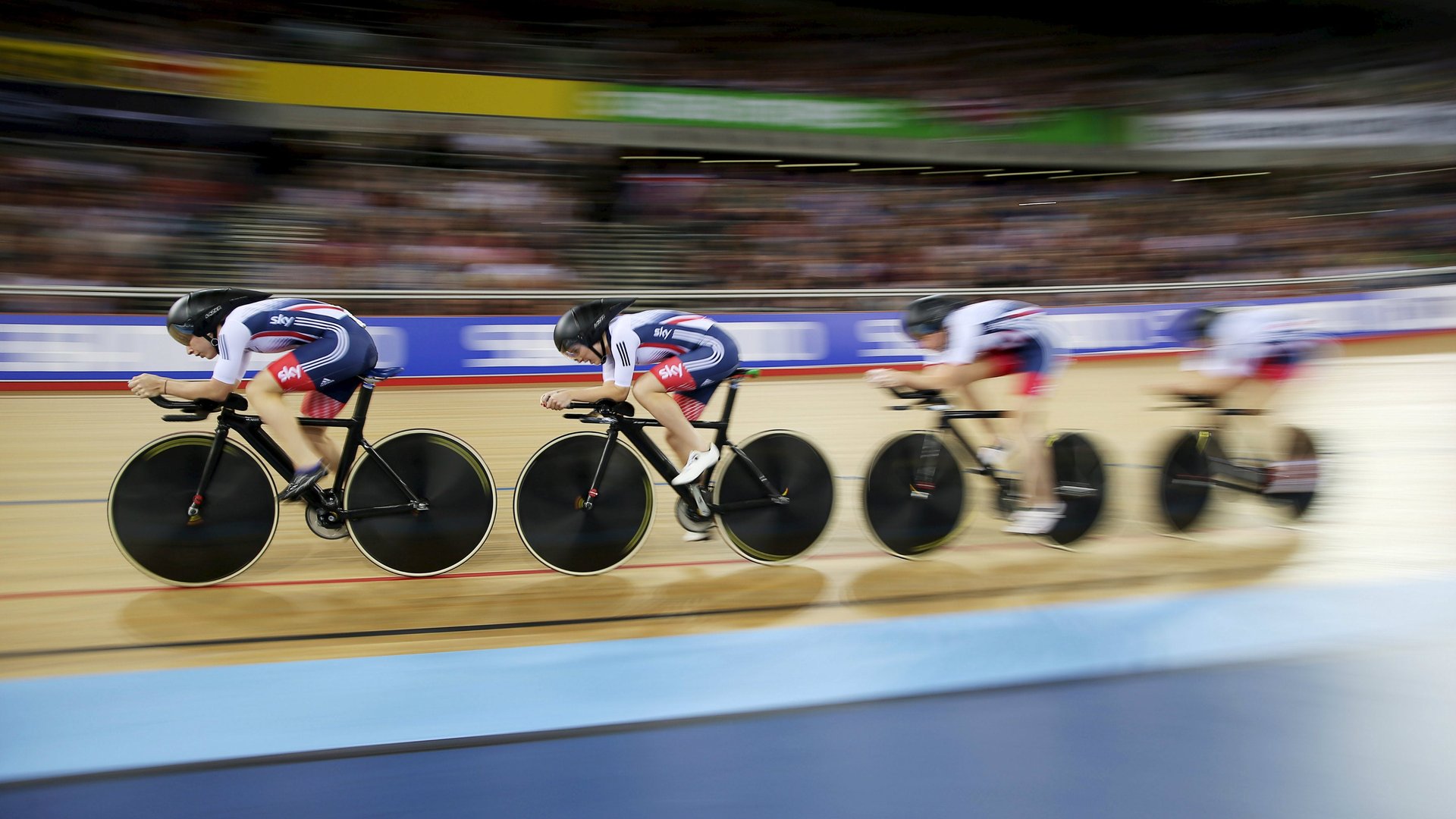

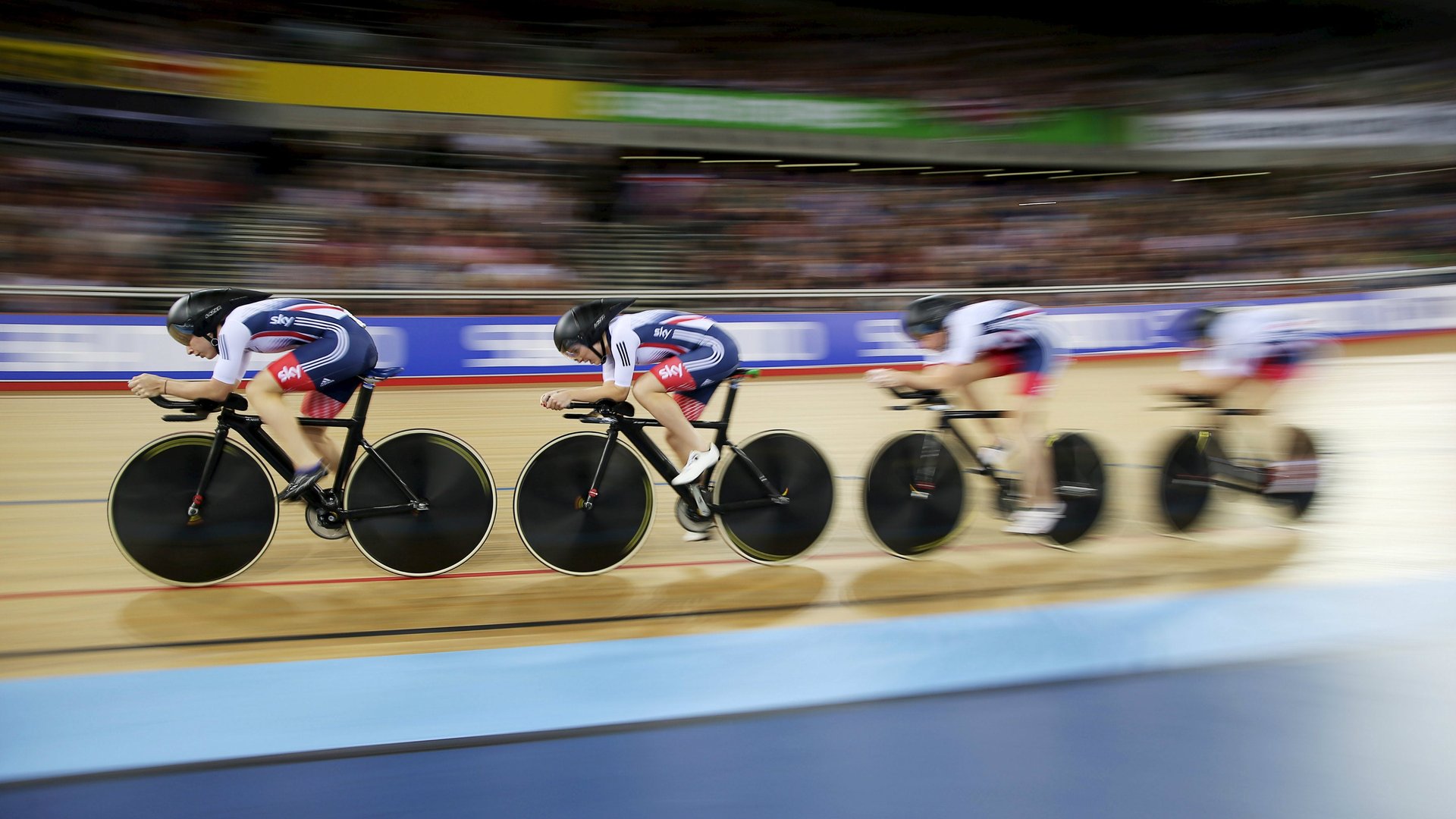

The summer of 2012 holds a special place in the history of cycling in the UK. London that year hosted the Olympic and Paralympic games, where British cyclists amassed 12 and 22 medals respectively, more than any other country in the sport. Weeks before, Bradley Wiggins became the first British rider to win the mother of all bike races, the Tour de France.

The summer of 2012 holds a special place in the history of cycling in the UK. London that year hosted the Olympic and Paralympic games, where British cyclists amassed 12 and 22 medals respectively, more than any other country in the sport. Weeks before, Bradley Wiggins became the first British rider to win the mother of all bike races, the Tour de France.

In cycling, as with many sports, men’s races had long dominated the press coverage, sponsorship, pay, prize money, and funding. But in raising the sport’s profile across a broad audience, the successes of 2012 presented British Cycling, the sport’s national governing body, with an opportunity to get more women involved in the sport. It outlined its strategy (pdf) for doing so the following year.

One of the aims was to increase the number of women in operational and leadership roles. Progress is afoot: In a field where women make up just a fifth of the coaching workforce, the number of female cycling coaches has risen by 70% in three years. (It’s a similar figure in Europe, where 20% to 30% of all sports coaches are women, according to the European Commission.)

“I think [British Cycling] have uncovered something that all of us and every sport can learn from,” says Marlene Bjornsrud, executive director of the Alliance of Women Coaches, which organizes professional development programs for female coaches in the US.

How did they do it—and what lessons are there for other sports and businesses wanting to build, inspire, and retain their female workforce?

1. Support systems

In April, British Cycling rolled out Ignite Your Coaching, a pilot program that pairs coaches with mentors who meet with them every four to six weeks. Mentors offer technical coaching guidance, and help around softer skills such as confidence building, planning, and expanding one’s knowledge base.

Women Ahead, a group that runs mentoring programs in sport and business, is helping with the design of the program and the matching process. This follows an earlier, year-long collaboration with British Cycling in which mentors from the electronics firm Ricoh were paired with more than a dozen women in leadership roles at the governing body.

“Being listened to and having someone to talk to is very powerful,” says Liz Dimmock, founder and CEO of Women Ahead. Reflecting on the Ricoh—British Cycling collaboration, she says that people “felt the value of someone supporting them from another organization, and that time was being given to them. They were having conversations they would typically find more difficult.”

This dovetails with Bjornsrud’s findings from 2014. After holding roundtable discussions that year with more than 200 American female leaders in sport, she found that a lack of role models, mentors, and support were among the reasons women cited for leaving the industry.

Mentoring isn’t just about support, though. When it offers an alternative perspective—from a male mentor working with a female mentee or the mentor coming from a different organization, for example—mentoring can change perceptions for the better, for both the mentor and the mentee. Dimmock cites an example of a male mentor who said that after working with a female mentee, he could better understand the challenges faced by his female staff, which changed the way he leads his organization now. Whether in business or in sport, Dimmock says, we must “embrace the outside perspective.”

For other sports or governing bodies trying to boost their female coaching workforce, getting insight from the group you’re trying to support is key, says Helen Hiley, senior coaching and education officer at British Cycling. She advises organizations to “find out what the coaches need, not think ‘we know what’s best’.”

2. Structure

For Dimmock, mentoring has to have formality and structure to be meaningful.

She recommends what she calls a ”two-way learning partnership”: the mentors share their experience, but the focus is on guiding the mentees to help them come up with their own solutions. Fundamentally, Dimmock says, mentors act as a sounding board for mentees, answering their questions and adding structure to their thinking.

Having an end goal is the only stipulation for coaches and mentors involved in the Ignite program at British Cycling, Hiley says. But creating spaces for fellow coaches and mentees to meet and share their experiences is also powerful for confidence-building and adds an extra layer of support.

“Bringing people together for training equips them and expands their networks,” Dimmock says.

The Ignite program is heeding this advice. Its internal social networking site lets mentors and mentees ask questions and share lessons.

3. Visibly building the pipeline

One of the barriers to gender parity across many sports is the lack of an ample pipeline of talent for other women to follow. “We’re struggling here,” admits Bjornsrud. “So much of the challenge is young women aren’t seeing women in coaching positions, so they don’t think they belong.”

But even when women are in positions of leadership, just seeing it isn’t always enough. In the United States, 90% of women’s college teams were coached by women in 1972—today that figure is 40%.

Women Ahead worked with coaches from junior to top levels as part of British Cycling’s collaboration with Ricoh. Dimmock says that working at all echelons to build a diverse pool of talent is a crucial lesson for businesses and sports governing bodies alike.

4. Small steps

The Ignite scheme is still in its infancy, but Dimmock says that both sports and businesses should embrace incremental changes. “There is a long way to go in all sports, but what is positive is that [British Cycling] are making practical changes,” she says. “It’s good to see them being brave and creating these programs.”

Hiley adds that the group isn’t about to rest on its laurels. “We want to get that 70% up a lot more,” she says. ”We’ll keep going.”