Square is guilting us into tipping basically everyone

There are a lot of things we’ve come to expect when we buy a package of Girl Scout cookies: the joy of knowing we’re supporting troops of 10-year-olds, the addictive crumble of a Thin Mint. But most of us don’t expect to be asked for a tip.

There are a lot of things we’ve come to expect when we buy a package of Girl Scout cookies: the joy of knowing we’re supporting troops of 10-year-olds, the addictive crumble of a Thin Mint. But most of us don’t expect to be asked for a tip.

Yet that’s what happened when personal finance writer Nicole Dieker used her credit card to pay for cookies with a mobile-payments system. The awkward situation will sound familiar to those who’ve used Square. Since its launch in 2009, Square has, in the admiring words of Silicon Valley, “disrupted” credit card payments by making them accessible to small businesses that previously had to settle for cash. It’s also popping up in unexpected places, forcing customers to make new calculations about when, and how much, it’s appropriate to hand over a little extra cash.

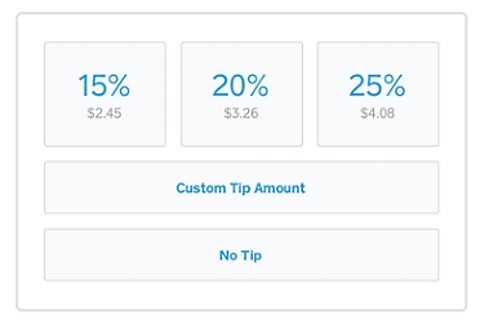

If you’ve paid with your credit or debit card at a food truck or local independent coffee shop in recent years, you’ve probably been confronted by the rounded, white Square terminal—and text asking if you’d like to tip a percentage of your total, perhaps 15%, 20%, or 25%.

“No tip” is an option too, of course. But when you’re being asked directly, under the expectant gaze of service workers, declining to offer something extra can feel petty.

The New York Times calls this phenomenon “tip creep.” Fast Company opts for the phrase “guilt tipping,” reporting that, “Square is facilitating tips at non-traditional venues—ice cream parlors, coffee shops, bakeries—places where tipping 20% (or tipping anything, for that matter) is not terribly common.” According to Fast Company, “Square is on track to facilitate roughly a quarter billion dollars in annual tips”—mostly at shops where customers would not have tipped before, or might have only tossed spare change into a jar.

For the most part, people seem to be taking tip creep in stride. “I’m the type of person who tries to tip 20% in restaurants and coffee shops, even if I picked up my own banana and carried my own paper cup to the coffee dispenser,” says Dieker. “It’s just easier to tip every time then to agonize over whether someone ‘deserves’ it, right?”

Indeed, Square and other POS systems are drawing attention to the fact that our informal gratuity systems have never really made sense. Delivery drivers receive tips, but plumbers don’t. Manicurists, yes; dental hygienists, no. The bartender who opens your beer expects an extra dollar or so, but the baker who iced your cupcake doesn’t—or, at least, didn’t until recently.

When it comes to eating out, people looking for some kind of rule of thumb could historically follow the sit-down/stand-up imperative. If you were planted in a seat while someone brought you a burger and fries, you were expected to tip at the end of the meal. That’s because federal law allows restaurants to pay servers well below the already-paltry minimum wage, so tips are built into waiters’ and waitresses’ expected compensation.

If you bought your burger and fries while standing up at a counter, by contrast, tipping was presumably optional: most fast-food workers earn at least minimum wage. But in an age when the difficulties of getting by on minimum wage have been well-publicized, the old logic of tipping doesn’t necessarily hold up to scrutiny.

“What makes some service personnel worth tipping and others not?” Eater.com news editor Daniela Galaza asks rhetorically. Rather than wrestle with the question of who deserves a tip, Square seems to suggest that customers simply shrug and say, “Everybody!”

Part of the reason for the general acquiescence to tip creep may be that Square is mostly a feature at high-end hipster shops—places that peddle what some might call “treats” and others might deride as “inessentials.” USA Today describes the kind of merchants who are adopting Square as “ranging from those hawking quirky goods to vendors at local farmers’ markets,” which sounds like a spectrum that’s straight out of the old blog “Stuff White People Like.” Customers who choose to patronize artisanal doughnut shops may be more likely to have an extra buck or two to spare for humanitarian reasons, having already decided that they can part with $4 for a raspberry-mascarpone-swirl.

To see how this class distinction plays out in the real world, I wandered over the two Asian lunch spots that recently opened next to each other on Lawrence Street in gentrifying downtown Brooklyn. One restaurant, Yaso Tangbao, offers Shanghai street food to cool kids and yuppies. Next door, Hibachi King offers up Japanese dishes to a more working-class crowd.

The restaurants’ prices are comparable, as is the wait for meals. But while Yaso Tangbao uses Square, Hibachi King doesn’t. When I asked the manager at Hibachi King why she elected not to install Square, even though it could facilitate tipping, she said, as though it were a sufficient explanation, “We’re fast food.”

That fact doesn’t stop the restaurant next door from actively soliciting tips. When I went to buy lunch at Yaso Tangbao, Square’s tipping screen brightly suggested that I tack on 15% or more to my take-out order. Even 15% seemed an excessive bonus to pay someone for throwing my Garden Vegetables Over Rice into a container, so I avoided the gaze of the cheerful woman at the counter, chose the “No tip” option, and scurried out of sight to wait. I felt frugal and guilty in equal measure. (The manager of Yaso Tangbao did not respond to my request for an interview.)

The best option might be to get rid of tipping altogether, raising prices on food and passing the extra revenue onto workers at restaurants and counter services alike. But restaurants that have attempted to eliminate tipping have so far experienced mixed results. Americans may grumble about tipping, but patrons are still reluctant to part with the tradition.

So as long as tipping is a part of our culture, people who are relatively well-off seem to feel a sense of responsibility to their fellow human beings behind the counter.

Charrow, a self-described “career barista” and trainer who has worked at Joe the Art of Coffee in Manhattan for almost a decade, says she has witnessed some changes in tipping behavior in recent years. But she attributes the shift less to Square and more to increased customer awareness of how little food service workers make and how much effort goes into making a high-end latte.

“I think in general more people tip than they used to,” Charrow said. “I think it’s because they recognize [coffee is] an art form and it’s become clearer to some that tips make up 50% of our income.”

Personally, I’d prefer to know that service workers in all industries are receiving a living wage, and I’m glad that the campaigns like Fight for $15 have made progress. In the meantime, it’s probably good that Square benefits people behind the counter: not merely small-business owners, who no longer have to risk putting off potential customers by being cash-only, but their employees, too, who have effectively gotten a raise—one that doesn’t cost owners a cent.