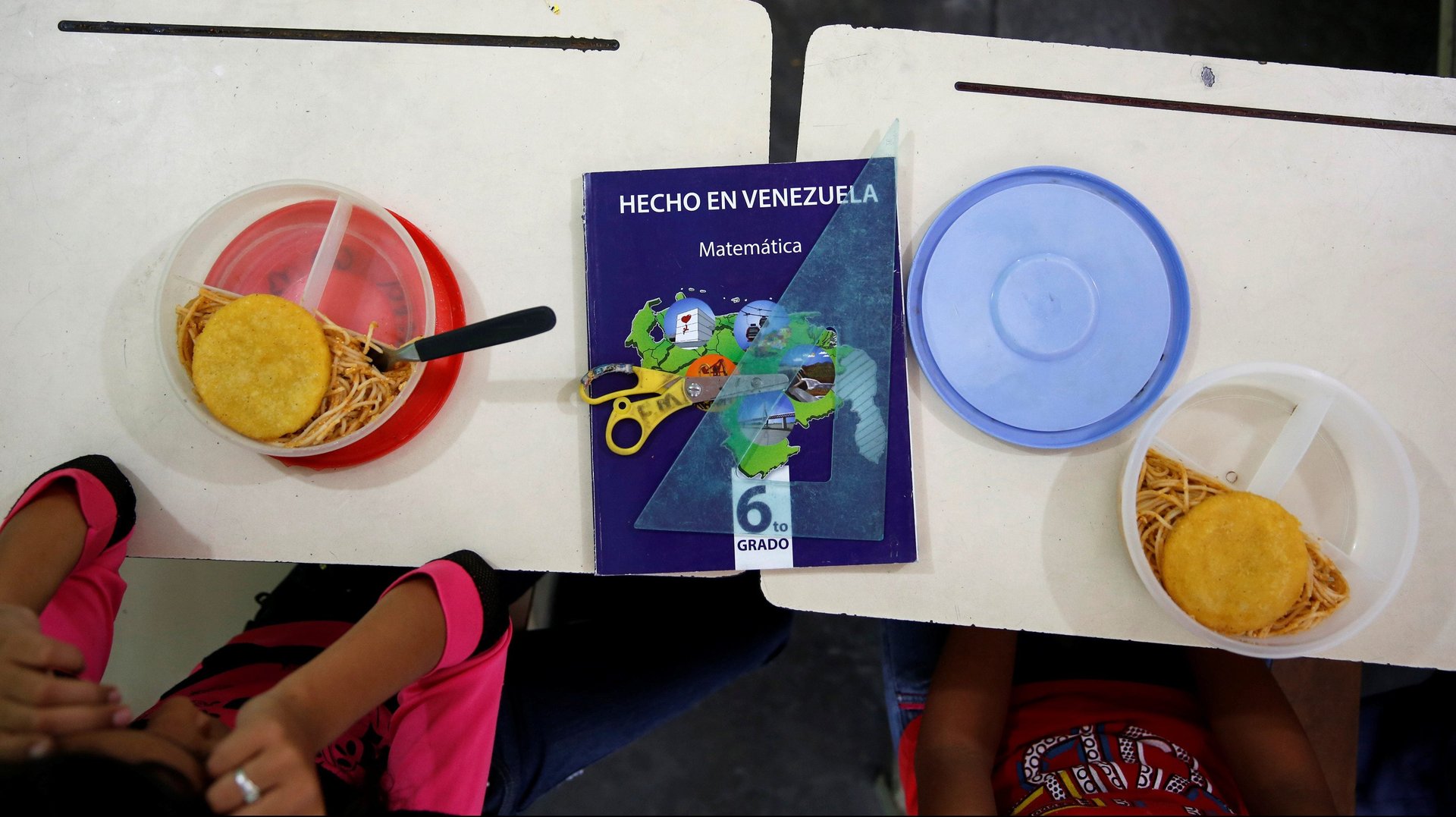

Venezuela’s food crisis has reached the country’s classrooms

Schools have become a microcosm of crisis-plagued Venezuela.

Schools have become a microcosm of crisis-plagued Venezuela.

Children are subject to the same belt-tightening going on throughout the country, where skyrocketing inflation and scarcity have forced more than 10% of Venezuelans to cut at least one meal a day (link in Spanish).

Teachers report that some students can’t concentrate (link in Spanish) because they haven’t had enough to eat. Others are fainting. Many don’t even come to class because their mothers need them to stand in supermarket lines. Experts say malnourishment and the spike in absenteeism because of it threaten to set the education system back years, if not decades.

As classes start letting out, some officials are see schools as a way to improve Venezuela’s alarming nutrition statistics. In the state of Miranda, for example, schools will remain open during the summer so that the poorest students can continue to receive state-sponsored lunches.

The summer program was created after a June survey (Spanish) among sixth-graders found that half of them have gone to bed hungry. For more than a quarter of the students, the government-sponsored snack they got in school was the only meal they ate during at least one day the week before the survey. The overwhelming majority, 86%, said they would like to attend school in the summer to eat.

“We were very surprised,” says Juan Maragall, education secretary for Miranda. “What kid wants to go to school during vacations?”

The state can’t afford to provide snacks to all of its 100,000 students, but it’s stretching its budget to feed the 10,000 who need it the most during the next few months. They will go to school from 9am to 11am, essentially only to eat. The summer program, like the food crisis, is unprecedented in Venezuela, says Maragall. “We’re learning how to manage hunger,” he notes.

Miranda’s governor, Henrique Capriles, has been pushing for a referendum to oust Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro. It’s unclear how Maduro’s government, which runs its own set of schools, will handle its free-lunch program during the summer. The Popular Power Ministry for Education, the national education agency, could not be reached for comment.

The national school feeding program, or PAE, for its acronym in Spanish, was touted by former president Hugo Chávez as a nationwide tool to fight malnutrition. Last fall, the official who oversees it told a Venezuelan newspaper that thanks to this program, Venezuela can boast “all over the world that it is certified as a territory free of hunger” (link in Spanish).

But independent observers say the PAE’s reach has been severely cut back (link in Spanish). Some schools report that they’re not getting supplies; some who’ve been getting them say they’re getting stolen, according to research from the local chapter of Transparency International, an anti-corruption nonprofit.

With fewer meals available, fewer students are attending school, something that is bound to erode Venezuela’s big gains in school enrollment during Chávez’s tenure, another much vaunted achievement of his Bolivarian Revolution. “A lot of children went to school to get the benefit of getting free breakfast or lunch,” says Tulio Ramírez, an education professor at Venezuela’s Central University.

Opposition lawmakers in Venezuela’s congress are trying to bulk up (Spanish) the national free-lunch program, though their proposal was shot down this week by government supporters. Chavista lawmakers argue that the endemic scarcity in the country is not caused by mismanagement but by an “economic war“ (link in Spanish) being waged by the country’s elites against the poor.

Even if a law is passed to order schools to make food available, it’s unlikely that universal free lunch will return to classrooms in time for the new school year. Supermarket shelves are bare because the government doesn’t have enough dollars to import goods. Local producers are in no position to fill in after years of business-hampering economic policies, such as expropriations and price and currency controls.

So far, Maduro’s administration has shown little intention of adopting the emergency measures necessary to restore food supplies in the long term. It is also blocking the only way to quickly get them, through international humanitarian aid. Its envoy to a June summit of the Organization of American States, a regional group, refused to receive donated goods from abroad, saying such offers are veiled attempts (link in Spanish) to intervene in Venezuela’s affairs.

In Miranda, Maragall is hoping the government changes that stance soon.