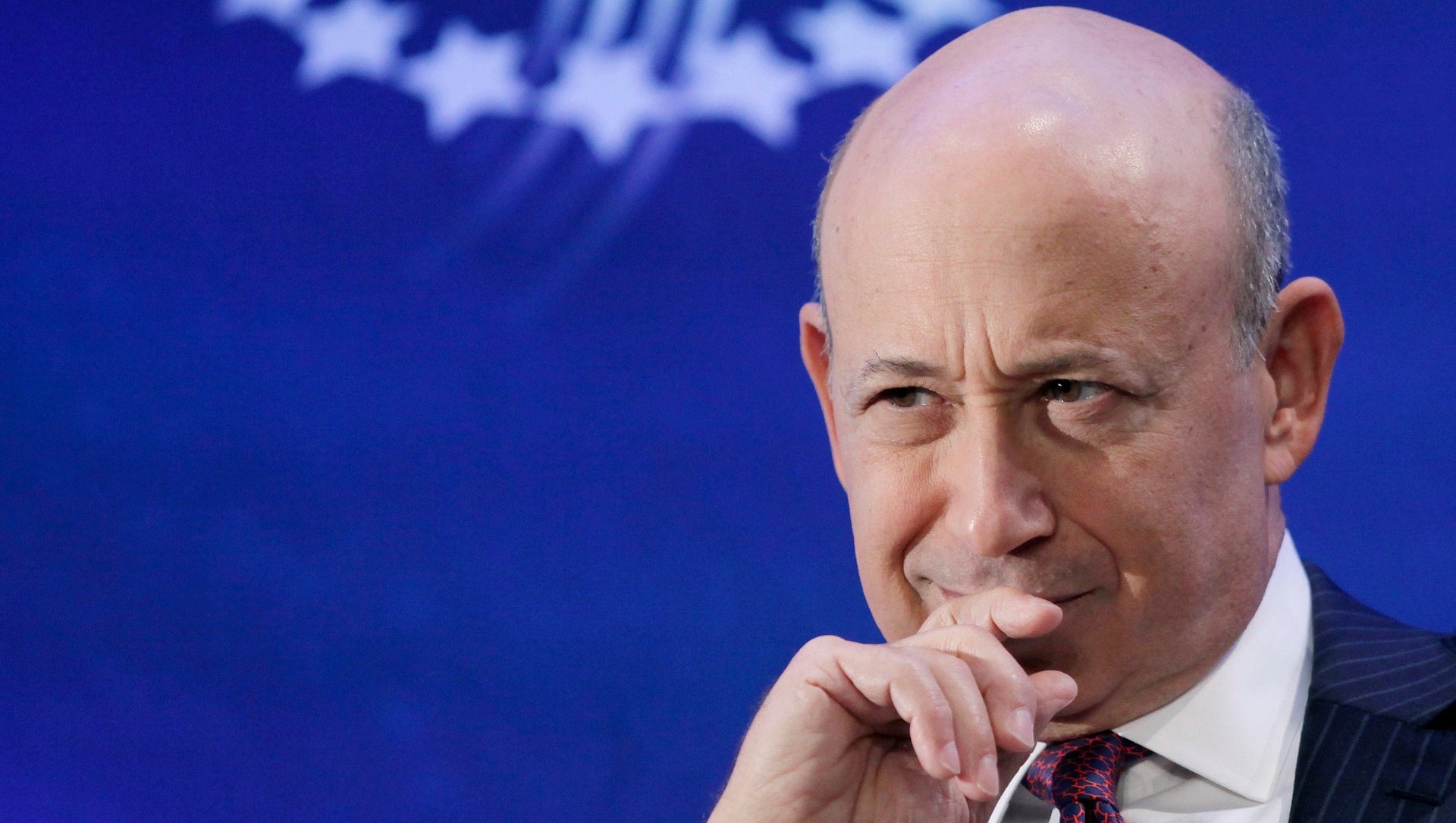

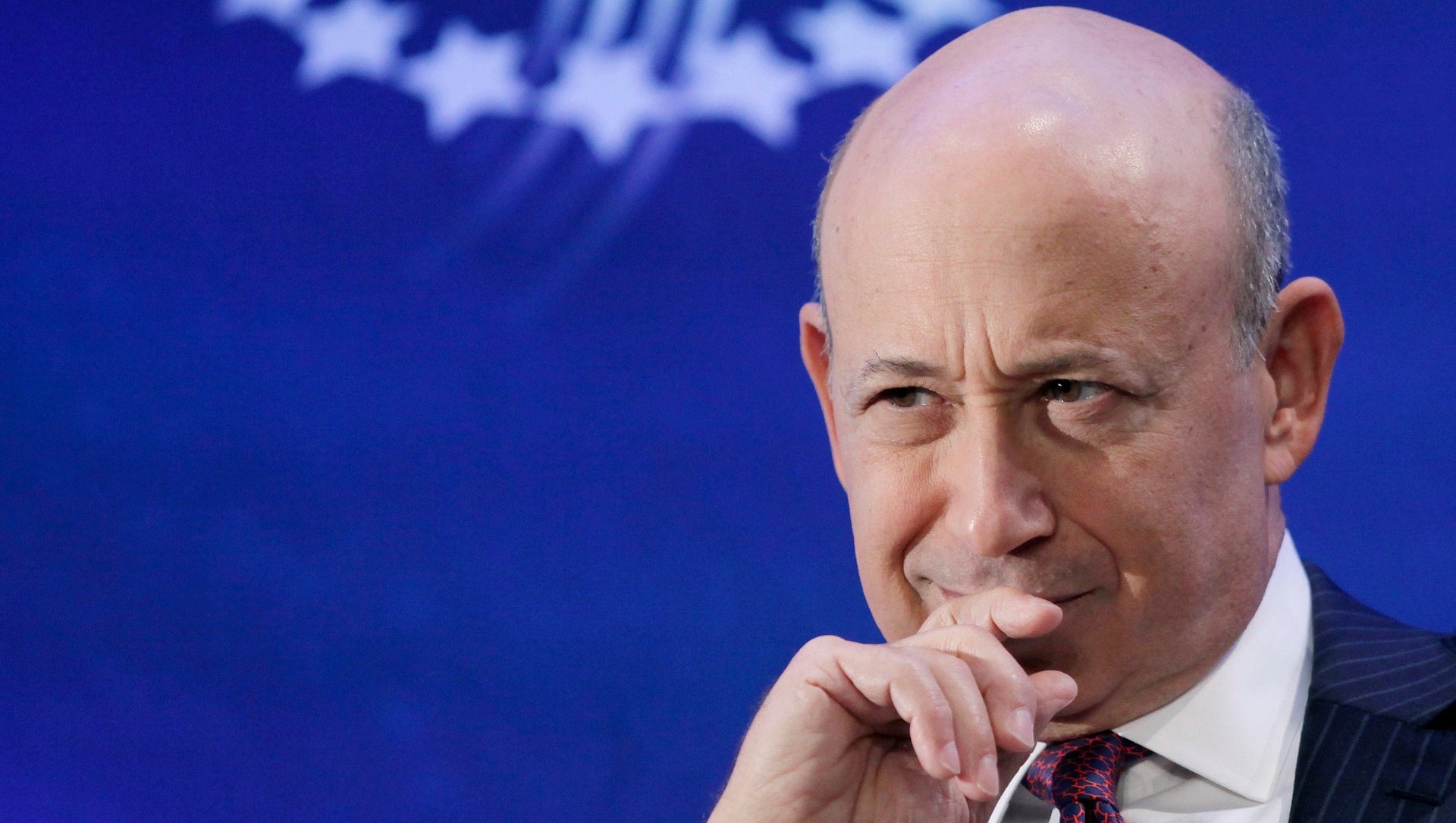

It’s not a victory, but Goldman shareholders chip away at Blankfein’s power

Lloyd Blankfein, the CEO of Goldman Sachs, has just avoided a second attempt to strip him of his other job—chairman of Goldman Sachs. But the Goldman shareholders who pushed to split his role into two did score some smaller victories.

Lloyd Blankfein, the CEO of Goldman Sachs, has just avoided a second attempt to strip him of his other job—chairman of Goldman Sachs. But the Goldman shareholders who pushed to split his role into two did score some smaller victories.

Corporate governance advocates argue that a board chairman should be independent and have no conflicts of interest. There are various banks where the roles are combined. Morgan Stanley’s Jim Gorman wears both CEO and chairman hats, as does JP Morgan’s Jamie Dimon. The dual roles also exist at Dell, Procter & Gamble and other firms. Other companies have a chairman who isn’t independent, like Walmart, where the chairman is the son of Walmart founder Sam Walton.

In Goldman’s case, the CtW Investment Group agreed to withdraw its shareholder proposal to separate the chairman and CEO roles at Goldman. In exchange, the bank agreed to expand the powers of its lead independent director, James Schiro. He will set the board’s agenda and write his own letter to investors. The independent directors will also meet more often. It’s not an outright victory, but it does chip away at Blankfein’s power and enhances independence on the board.

JP Morgan’s Dimon faces a similar fight at his bank, where shareholders have proposed taking away his chairman title. Before the London Whale trading mishap that led to a $6 billion loss, Dimon was seen as untouchable, but not any more. Parties on both sides are lobbying investors before JP Morgan’s annual shareholder meeting next month. If the vote looks like it could be close, JP Morgan may have to make a compromise similar to Goldman’s.

Separating the chairman and CEO roles matters most at troubled companies, who need the oversight. As shareholder pressure grows at those kinds of firms, it will be harder for companies to keep pushing back. They don’t want to risk being seen as unfriendly toward shareholders and lax in corporate governance. An even worse fate would be an embarrassing loss on a shareholder vote. Investors can use those worries to keep ratcheting up little victories toward the bigger goal.