SoftBank’s $32 billion bid for ARM proves Masayoshi Son is back in the driver’s seat

Japanese telecom and tech giant SoftBank Group will announce today (July 18) a $32 billion takeover of British microchip designer ARM Holdings, according to numerous media reports.

Japanese telecom and tech giant SoftBank Group will announce today (July 18) a $32 billion takeover of British microchip designer ARM Holdings, according to numerous media reports.

The deal for ARM, dubbed the “most precious jewel” in Britain’s technology industry, suggests that SoftBank CEO and founder Masayoshi Son is back in charge of his company, and running its prized investment unit again, after a public fallout with named successor Nikesh Arora.

SoftBank generates most of its profit from its telecom business in Japan. But it’s best known globally for making bold investments in other companies.

Under Son, these bets have been sporadic and quite risky. Son’s $20 million investment in Alibaba in 2000 was, at the time, an exceptionally large bet that e-commerce could thrive in China. He turned out to be right, and earned $87 billion back on it. But his $20 billion bet on Sprint has yet to spark a turnaround for the troubled US telco.

In 2014, Son hired Nikesh Arora as the company’s president and COO, and his potential successor. The former Google executive ramped up the timing of SoftBank’s investments, and tilted his focus towards India. Arora invested over $2 billion in dozens of Indian startups throughout his tenure.

Unlike Son’s bets, these plays were more akin to a traditional Silicon Valley investor picking one player in a crowded sector—a food delivery startup here, a hotel-booking startup there. This ruffled feathers within SoftBank, and ultimately prompted Arora’s departure in June.

A $32 billion bet on ARM is more Son’s style.

While few consumers may have heard of ARM, smartphones probably wouldn’t exist without it. The Cambridge-based company designs microchips and then licenses out the designs to companies like Apple, Samsung, and Qualcomm, which then modify them and place them into computing devices. ARM’s sales have surged amidst the global smartphone boom—last year more than 15 billion chips shipped containing the company’s designs.

Since SoftBank is a telecom, investment, and holding company, it’s not clear how it can help ARM make money beyond providing cash. Ben Evans, an investor at Andreessen Horowitz who follows the industry closely, says it “feels more like investing logic than industrial logic.”

But both companies want to get rich off the next wave of post-smartphone hardware devices—even though it’s not clear what those devices might be. ARM has invested in improving infrastructure for the so-called “internet of things,” a term used to describe how ordinary appliances (refrigerators, watches, toasters) will connect to the internet and communicate with other devices. More internet-enabled hardware means more sales for ARM.

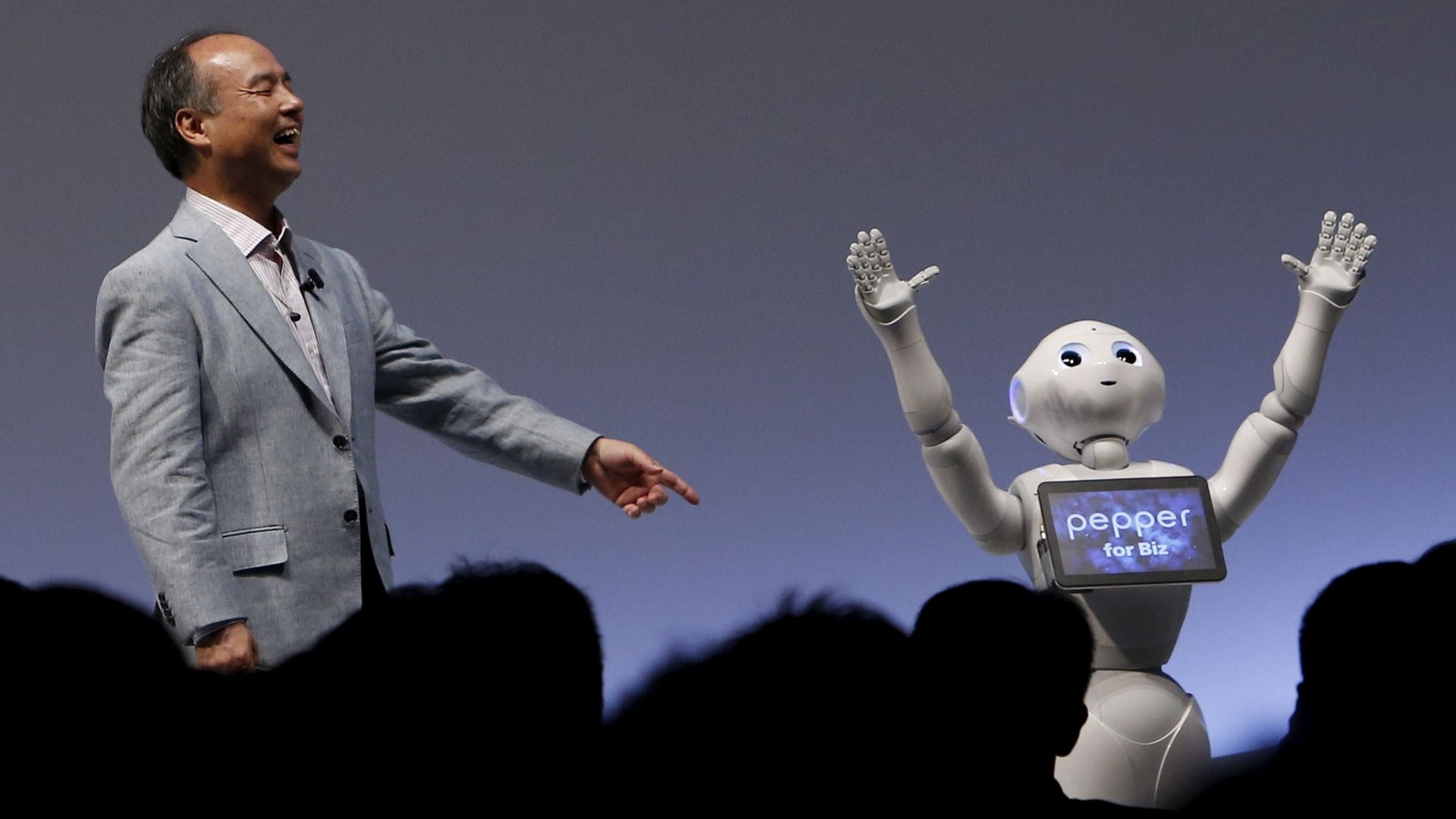

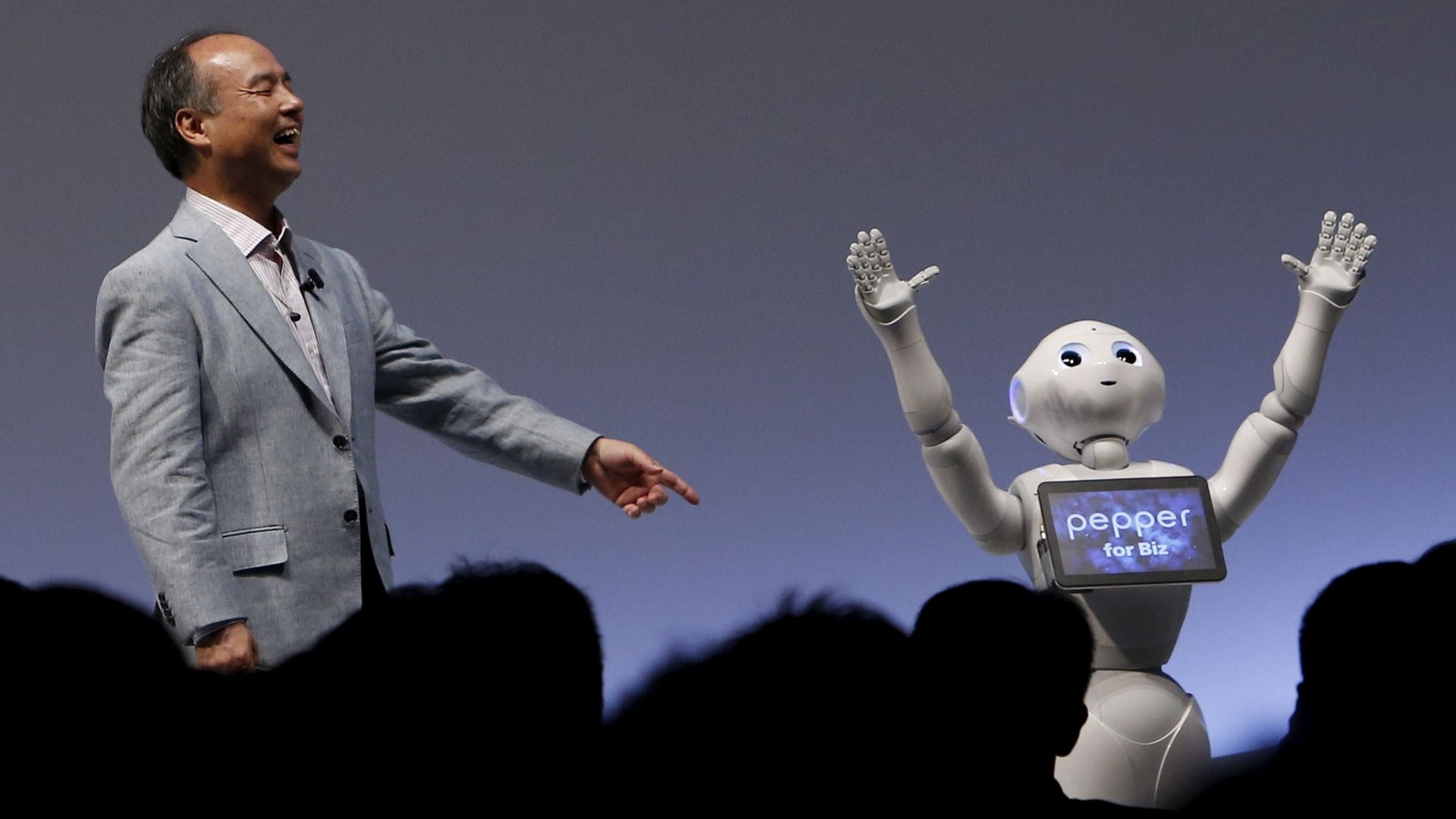

Son is a believer in the internet of things too. “Each individual, on average, will have more than 1,000 devices that are connected to the internet by 2040,” he said at a company conference in 2014. He has also aggressively promoted Pepper, a humanoid cutesy robot that might eventually—if you believe Son’s claims—welcome guests in retail shops and restaurants worldwide.

Instead of, as Arora did, making relatively small bets on internet companies with largely-proven business models—ride-hailing, e-commerce—Son is investing in a sector that has not yet blossomed, but could potentially be huge. If he succeeds, he’ll once again be hailed as a genius investor. If he doesn’t, his strategy may be remembered as no better than the man he booted out.