Mark Carney won’t be able to save Britain from itself

When Mark Carney arrives at the Bank of England in June he will do so with a heavy weight of expectation on his shoulders.

When Mark Carney arrives at the Bank of England in June he will do so with a heavy weight of expectation on his shoulders.

The new mandate he will inherit shifts the bank’s focus from its 2% inflation target to an inflation forecast target with forward guidance of policy decisions. In theory, at least this should both enhance the communication of monetary policy to the public and allows the bank’s Monetary Policy Committee scope to accept under- or over-shoots in inflation relative to target in the short term.

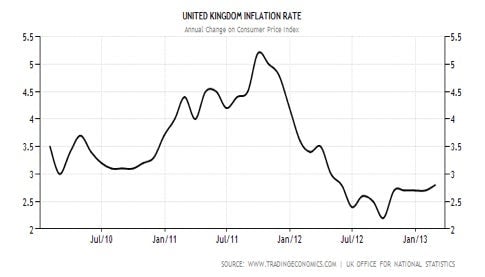

For many, however, this was simply an acknowledgement of the Monetary Policy Committee’s decision to leave its base interest rate at 0.5% since March 2009 despite persistent above-target inflation:

Even those who had been advocating for a change in mandate were disappointed as the Chancellor stopped short of a nominal GDP level target, which would have loosed Carney’s hands even further.

It is nevertheless clear that Osborne is looking for the bank to remain accommodative in an effort to offset his fiscal consolidation program. Although he was vague in the detail, government spending cuts after the next election implied, though not announced, in the Budget are a cause for concern.

As the Institute for Fiscal Studies wrote in its report on the Budget:

The implication is that the real effect of public spending cuts pencilled in for the next parliament will be even more severe than expected hitherto. Add to that the fact that we are promised more capital spending, more spending on social care, and a more generous childcare subsidy, within an overall spending envelope that has not been expanded and the outlook for all other unprotected spending looks grim indeed.

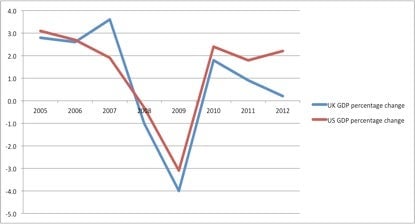

So the key question is how effective has monetary policy been at offsetting government efforts to reduce the fiscal deficit. Here it is helpful to look at the UK’s recent economic performance versus the US:

What is clear from the chart is that the trajectories of the two countries were relatively similar both going into the crisis and in the sharp bounce-back that started in March 2009. However, from 2010 onwards there is a clear divergence with UK growth slowing sharply.

There are multiple explanations for this. The first is that fiscal consolidation efforts have hit growth both directly by reducing demand and indirectly through discouraging private sector investment as they see their available market contract.

A second line taken is that the treasury and the bank have made weakening the pound an implicit policy as it should, at least in theory, have prompted an increase in exports and improved Britain’s trade balance. Yet if this was the hope it has been cruelly dashed by a combination of external shocks, such as the eurozone crisis, and the relative weakness of the UK manufacturing sector.

Chris Giles, economics editor of the Financial Times, is one of the proponents of the latter view. He argues:

[By] far the most important cause of stagnation was the terrible export performance. Had foreign sales last year performed as the OBR forecast in late 2011, nominal gross domestic product would have been £13.6bn higher by the fourth quarter and the annual growth rate would have been 4.9 per cent not 1.3 per cent.

Relying on an export boom to lead the country out of a crisis while loose monetary policy smoothed the transition was always a gamble. The fact that it has not materialized should in itself worry the Chancellor, but all the more concerning is that he is still looking to monetary policy to paper over the cracks despite the fact that it appears to have only had a limited impact in offsetting the weakness in output so far.

With a financial system in the process of deleveraging, household real incomes falling and an apparent dearth of investment opportunities in the UK the transmission mechanisms of central bank policy into the real economy are limited.

As such we can perhaps look at another way that monetary policy can feed into output—government investment.

Unfortunately there are no signs yet that Britain’s Chancellor is moving in this direction. Without a policy shift when Carney takes over from Mervyn King he will be inheriting a heavy burden indeed.