Can architecture make people trust cops?

In North Lawndale, Chicago, a public basketball court is changing the way people relate to local police. Built just last October, it’s a half court built right next to the West 10th district police station, and it’s designed to get cops to shoot hoops with young men and women they might otherwise never meet.

In North Lawndale, Chicago, a public basketball court is changing the way people relate to local police. Built just last October, it’s a half court built right next to the West 10th district police station, and it’s designed to get cops to shoot hoops with young men and women they might otherwise never meet.

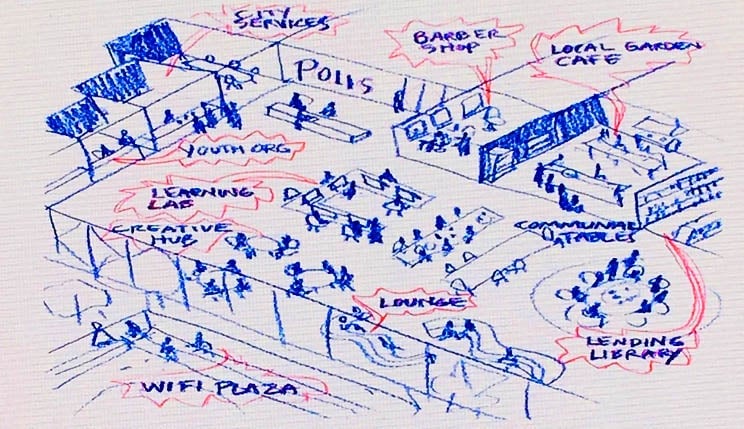

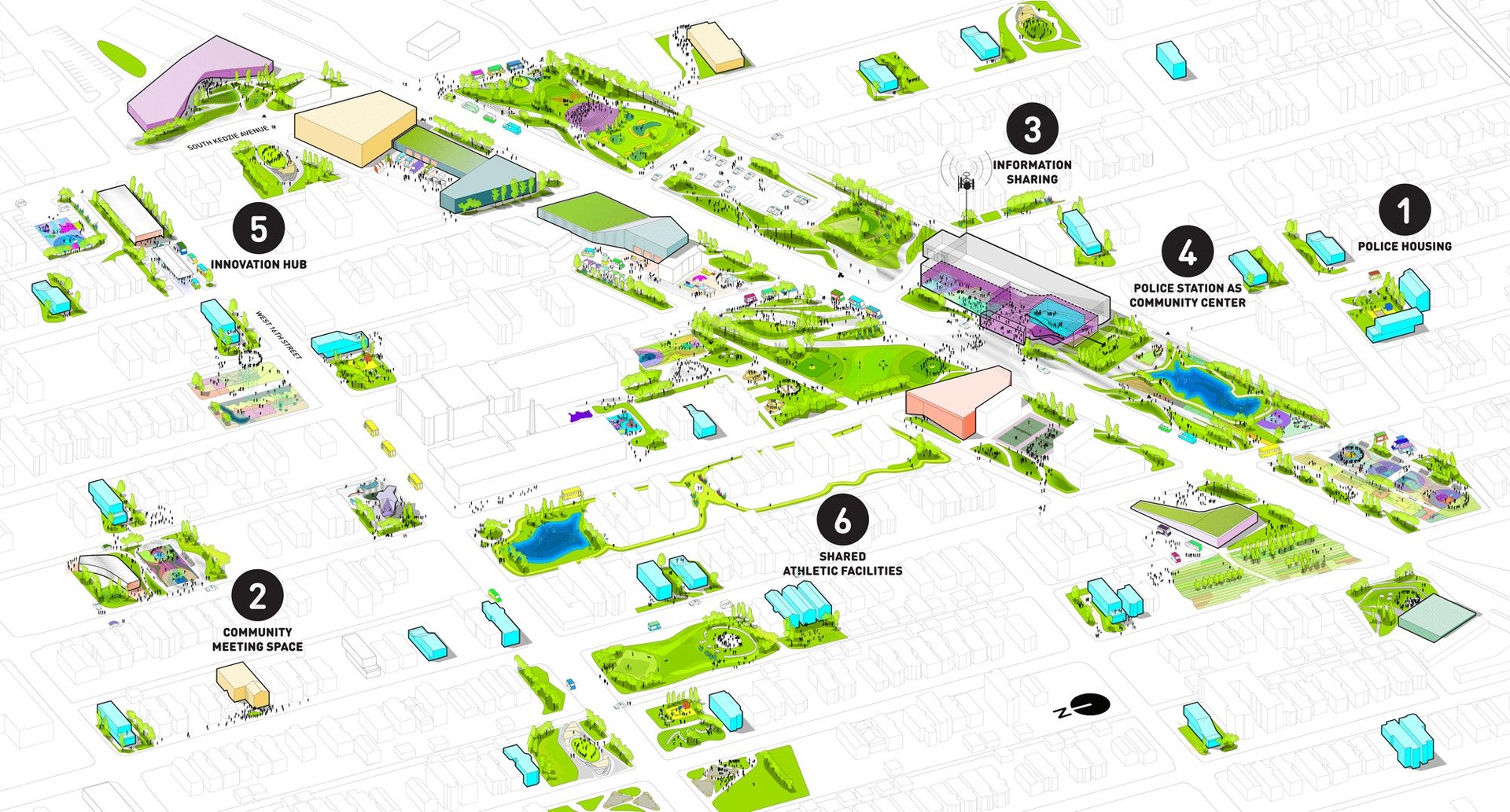

Conceived by MacArthur “genius” and architect Jeanne Gang, the simple project is part of her broader proposal to reimagine isolated, fortress-like police precincts as welcoming community centers. In her vision, better police precincts could house a barber shop, a garden, a gym, and lounges with free wi-fi—all designed to draw community members to hang out in stations and eventually build friendlier and more trusting relationships with the cops sworn to protect them.

The concept for Polis Station as its called, was shaped around a 2015 report on 21st Century Policing by a task force convened by President Barack Obama. Almost 1,000 people were shot by the police in 2015 alone, and 250 have been killed in the first quarter of 2016 according to a Washington Post survey.

The committee’s top recommendation stressed the need to re-establish trust and mutual respect between law enforcement and citizens. “Law enforcement culture should embrace a guardian—rather than a warrior—mindset to build trust and legitimacy both within agencies and with the public,” as stated in the report.

But of the many inter-disciplinary recommendations, Gang noticed that the report’s authors forgot to address spatial aspects that can foster a sense of community. “It made me think, are there ways design can help improve the relationship between community members and police if we look at the architecture?” says Gang at the New York Times Cities for Tomorrow conference last Tuesday (July 19). “Not that it can solve everything but maybe it can be part of the dialogue.”

The name “polis” comes from the Greek ideal city-state governed by a sense of close community ties.

For a radical rethink of friendly police buildings, Gang decided to shake up her own design process. Instead of starting at the drawing board, her studio went to Chicago community members and law enforcement officers for design tips.

“Sometimes designers are afraid to engage communities directly, including me because [I’m thinking] what are they going to say to threaten my aesthetic,” confessed the creator of Chicago’s latest architectural marvel, the Aqua Tower. ”But there were so many great ideas and things that I would not have thought of myself.”

Gang’s plan features creative ideas for repurposing abandoned parking lots and parking garages surrounding a precinct. Polis paints an idyllic mix-use complex with sports facilities, outdoor theaters, cafes, places of worship, markets, a community vegetable garden, meditation zones and public housing for cops and community members.

Some low-budget interventions include providing free wifi or introducing a bench outside buildings. After debuting Polis Project for the Chicago Architecture Biennale last year, Gang plans to actively showcase her ideas in more cities across the US. Her firm has also implemented these community-friendly principles in the design of a new fire station in Brownsville, Brooklyn, one of the poorest and most dangerous neighborhoods of New York City.

Gang says the community meetings helped define a new process for her studio. “When we learn to design, as architects we pin up our drawing and learn how to defend our designs but we don’t actually learn how to engage with communities,” says Gang. “I think it’s a thing that everyone needs to know how do. It’s the future of design.”