Police in Michigan are trying to 3D-print a murder victim’s fingerprint to unlock his phone

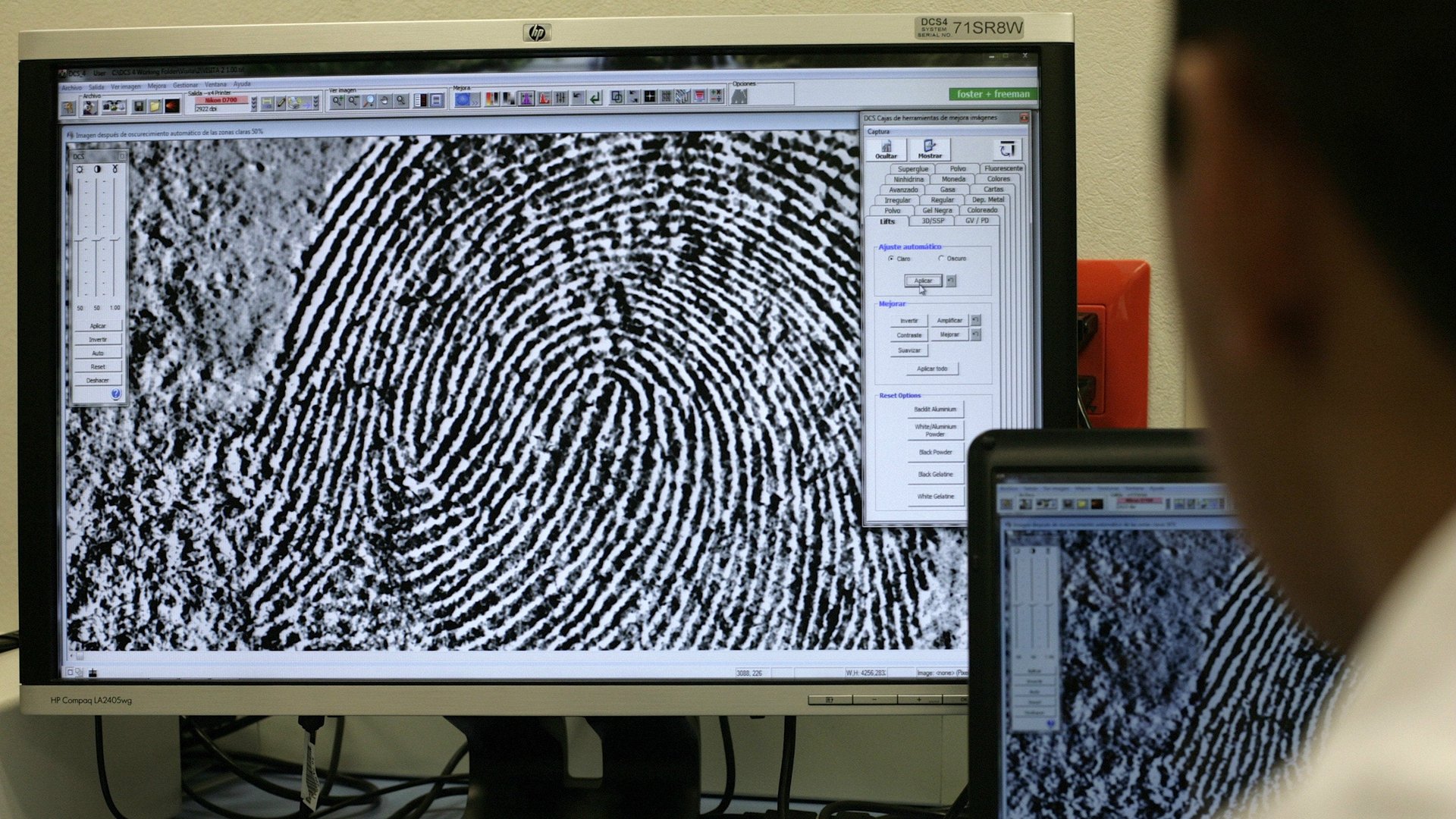

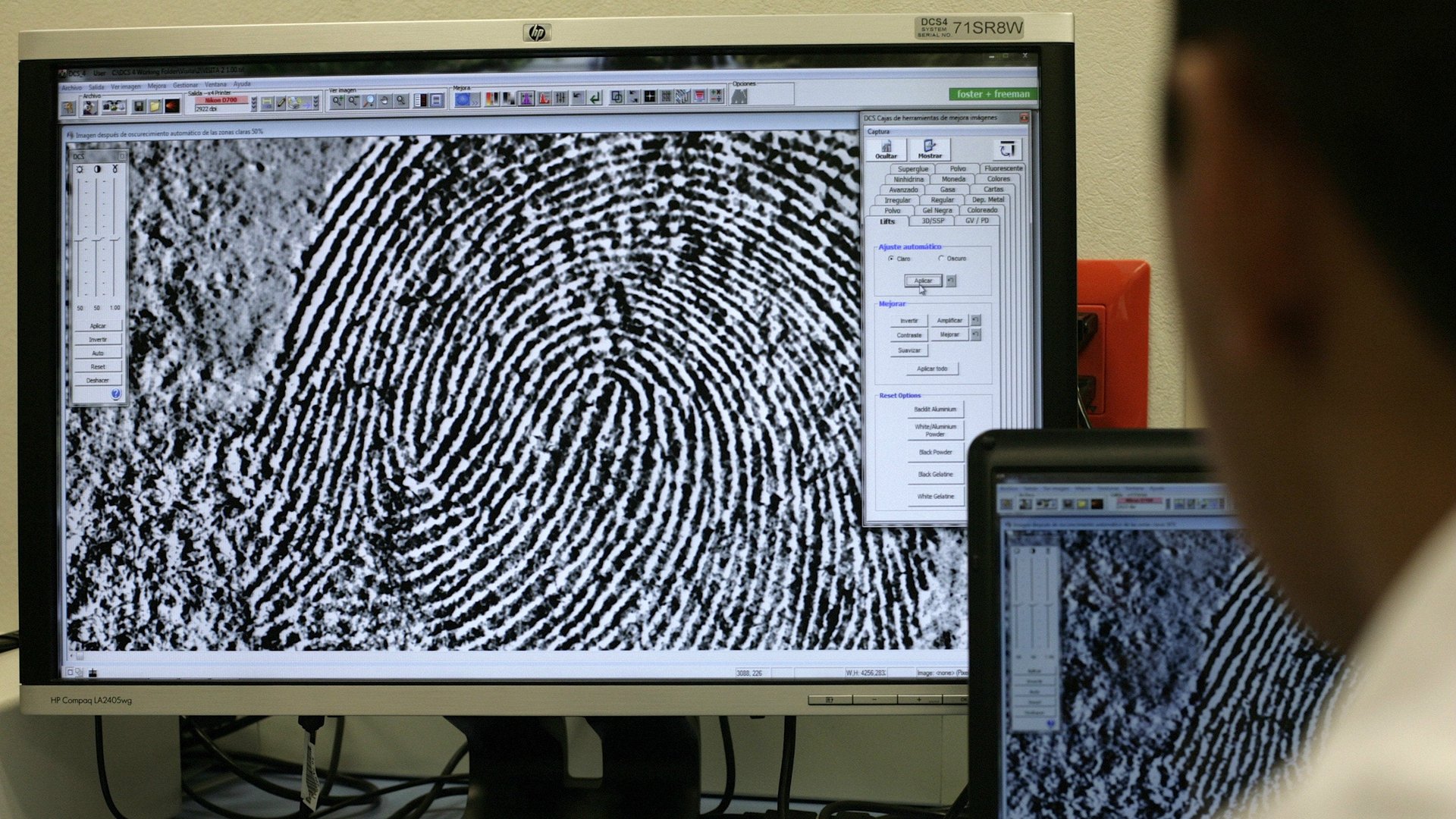

A research lab at Michigan State University, trying to show how easily our devices can be hacked into, has been using printed fingerprints to spoof mobile-phone sensors. Then the police got involved.

A research lab at Michigan State University, trying to show how easily our devices can be hacked into, has been using printed fingerprints to spoof mobile-phone sensors. Then the police got involved.

After becoming aware of their research, the digital forensics and cyber-crime unit at Michigan State University’s police department approached the lab last month for the very opposite purpose: using this technology to try to solve a case.

Working on behalf of another investigating agency, police wanted to access the phone of a homicide victim, and asked the research team to 3D print a replica of the victim’s fingerprints in the hope of unlocking the device—a Samsung Galaxy S6.

Detective Andrew Rathbun told Quartz he was “wracking” his brain trying to think of ways to unlock the device. He said:

I Googled ‘spoof fingerprint’ or something like that and came across [the research (pdf)] as one of the results. I read the research and noticed it was based out of MSU, much to my surprise. I simply emailed those who did the study and set up a meeting.

Sunpreet Arora, a PhD student at MSU’s department of computer science and engineering, told Quartz that the police had scans of the victim’s fingerprints from a previous arrest, which they gave to the research lab. The team turned those flat, 2D prints into a digital 3D model using an algorithm, then printed it off using a 3D printer and a rubber-like material.

This was coated with a thin layer of metallic particles to make it more conductive.

Arora confirmed that the 3D-printed replica fingerprints required more testing before they could be handed back to police to unlock the device—so it’s unclear yet whether the method works. The initial results, he says, “have been promising.”

“The hope is that information leading to the arrest of the perpetrator exists on the phone,” Rathbun said. “That won’t be known until we get into the phone, which we currently have not been able to do yet.”

Rathbun added: ”It’s pretty amazing that this capability is right down the street from my office. Here’s hoping it works!”

This may well be the first case of law enforcement using such technology as part of an ongoing investigation—though it harks back to the questions of privacy and security raised by the dispute between Apple and the FBI earlier this year, in which investigators demanded the company develop software to unlock the iPhone of one of the San Bernardino shooters.

Apple fiercely resisted the request, calling it an “overreach” by the US government. Investigators were eventually able to break into the device without Apple’s help.

Quartz has reached out to Samsung for comment.