Google, Microsoft, and other corporate giants are quietly showing a movie about teen internet addiction

About halfway through the documentary Screenagers, one kid lays out the rules of a game he plays with his friends whenever they’re at restaurant: Everyone puts their phone in a pile in the middle of the table during the meal. Whoever pick theirs up first has to get the check.

About halfway through the documentary Screenagers, one kid lays out the rules of a game he plays with his friends whenever they’re at restaurant: Everyone puts their phone in a pile in the middle of the table during the meal. Whoever pick theirs up first has to get the check.

Good one, right? Here’s a kid who has started to figure out how to tame the roaring interruption monster we call the internet.

Most everyone else in the film

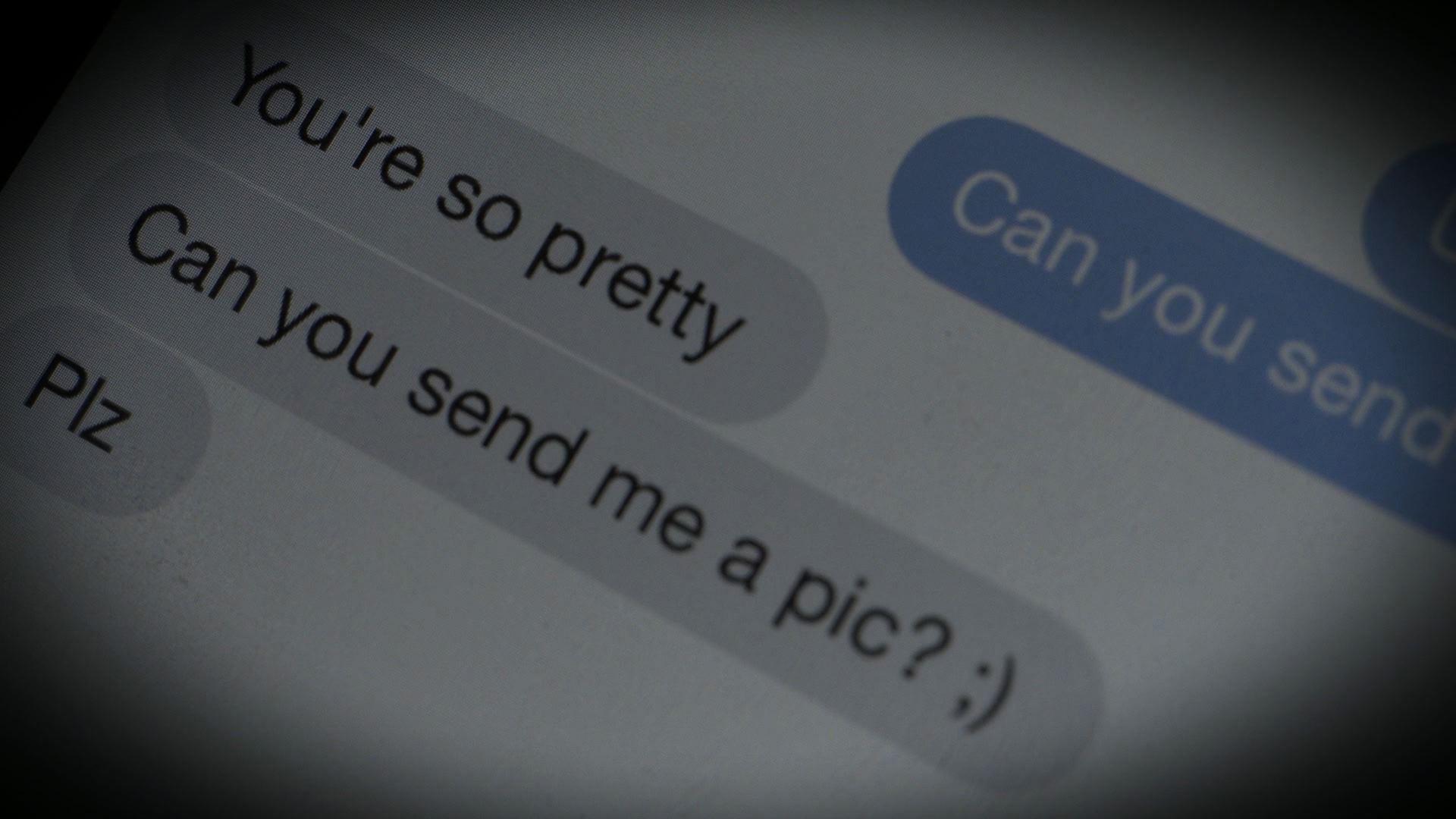

Screen use and abuse and how it disrupts childhood and family life are at the center of the independent documentary, Screenagers, Growing up in the Digital Age, playing in community centers and film festivals around America. It is the creation of Delaney Ruston, a parent, filmmaker and primary care doctor and follows her on a quest to educate herself about how being constantly wired affects the kids she treats and her own children.

The movie has developed a passionate fan base with parents and school administrators, but it’s also being shared like a hot stock tip inside companies at the behest of people who work with technology. So far, at the urging of company technologists, Screenagers has played at nearly two dozen US businesses ranging from Google, Microsoft and Adobe, to Starbucks and Monsanto, to Pixar and Disney’s animation studio.

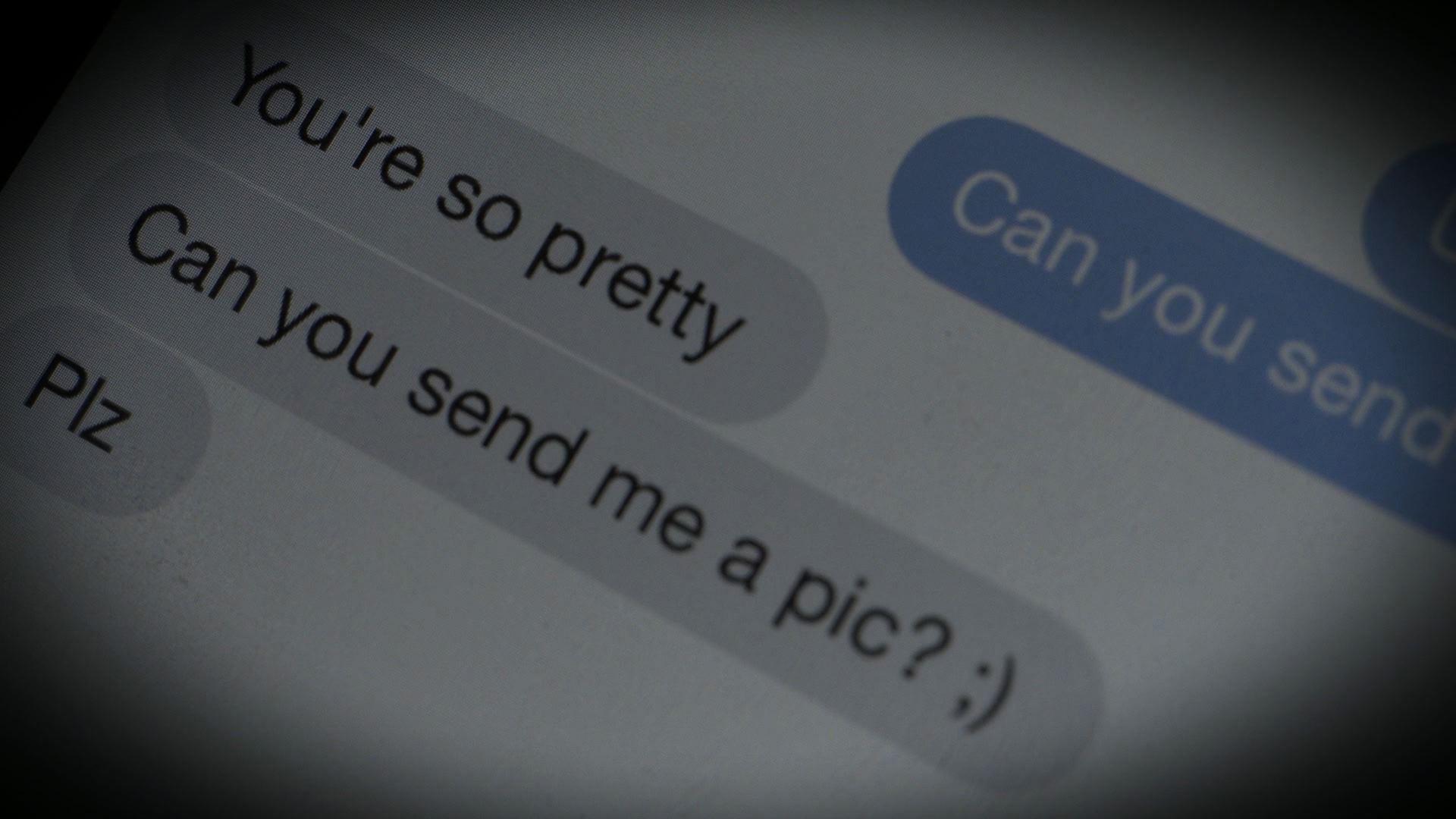

The films takes us inside the eye-rolling, door-slamming world that Delaney navigates with her teenage daughter as they dance around control of a new iPhone. They debate limits, write and sign contracts, only to have to trash them and rewrite them later. We also watch the harrowing stories of other families. One bright college student ends up in a treatment facility for internet addiction after he throws away his life for online gaming. A young girl seeking acceptance from her peers is pressured into sharing sexy pictures on social media and finds herself slut-shamed instead.

Peppered throughout the film are insights from experts about the impact of devices on our health, and statistics laying out the landscape. While the numbers are depressing–we spend on average of 6 ½ hours a day looking at screens, teenage boys spend on average 11.3 hours a week playing video games–the movie also offers guidance and positive steps parents and teens can to take refocus attention. Screenager’s website has a deep well of resources: where to find help, anti-bullying campaigns, parental control apps and how to find or set up a screening. The self-help aspect of the site is in part what is driving the rise of community around the movie.

Kevin Clark, father of two teenagers and head of systems at Lucasfilm, organized a showing for his co-workers and their kids at the company’s wood-paneled state-of-the-art auditorium, a space usually reserved for academy screenings. He says he’s seen parents in the affluent area of Marin county California discover the pitfalls of giving their kids wide open access to the web. Clark even set up limits on a home router for one desperate mom whose son’s pornography habit was out of control.

After the screening, Clark facilitated a conversation with the audience, making sure the kids had a chance to speak. He said that people were feeling as if they were battling their own battles but “When you get a chance to talk about it together you realize there are others struggling with the same issues.”

Jeff Brzycki, the CIO of the software company Autodesk, arranged showings for his colleagues after seeing the movie at his son’s middle school. Brzycki says that while he understands as a culture that we’re just beginning to work out our relationships with technology, he thinks our attention has been hijacked. On a recent family vacation to Mexico he was stunned to watch a boy float down a lazy river in an inner tube face down in his phone, missing the scenery entirely.

Brzycki is worried that “this is being hardwired into our kids.” He says companies need to be responsible about what they’re putting on the glass in front of customers especially because of “the incredible power a user interface has over the brains of the people on the other size of the device.”

Parent Lorraine Rizzuto, a troop leader and web manager at Girl Scouts of America shared the movie with colleagues and also created a Screenagers patch, which her troop of girls can earn by completing a digital citizenship program. She felt it was important to help her colleagues and created the patch so she could also be “moving at the speed of the girls.”

As the films plays in school auditoriums and company conference rooms around the US it’s clearly touching a nerve with parents. Reaching screenagers themselves however, may be a bigger challenge. After a showing in a middle school in Brooklyn, New York, recently, Imani, a rising freshman was asked her take-away: “Honestly, I may or may not have fallen asleep in the middle of it.”