For ExxonMobil, having oil is one thing, but pumping it is another

Here is a puzzle: ExxonMobil has sufficient proven oil and gas on its books to produce at current levels for 16 years. It has 55 years of supply in its total resource base, which is those proven reserves plus deposits to which it hasn’t yet committed the development dollars required before legally calling them “proven.”

Here is a puzzle: ExxonMobil has sufficient proven oil and gas on its books to produce at current levels for 16 years. It has 55 years of supply in its total resource base, which is those proven reserves plus deposits to which it hasn’t yet committed the development dollars required before legally calling them “proven.”

In short, ExxonMobil’s oil and gas inventory—the largest of any company on the planet—is bursting.

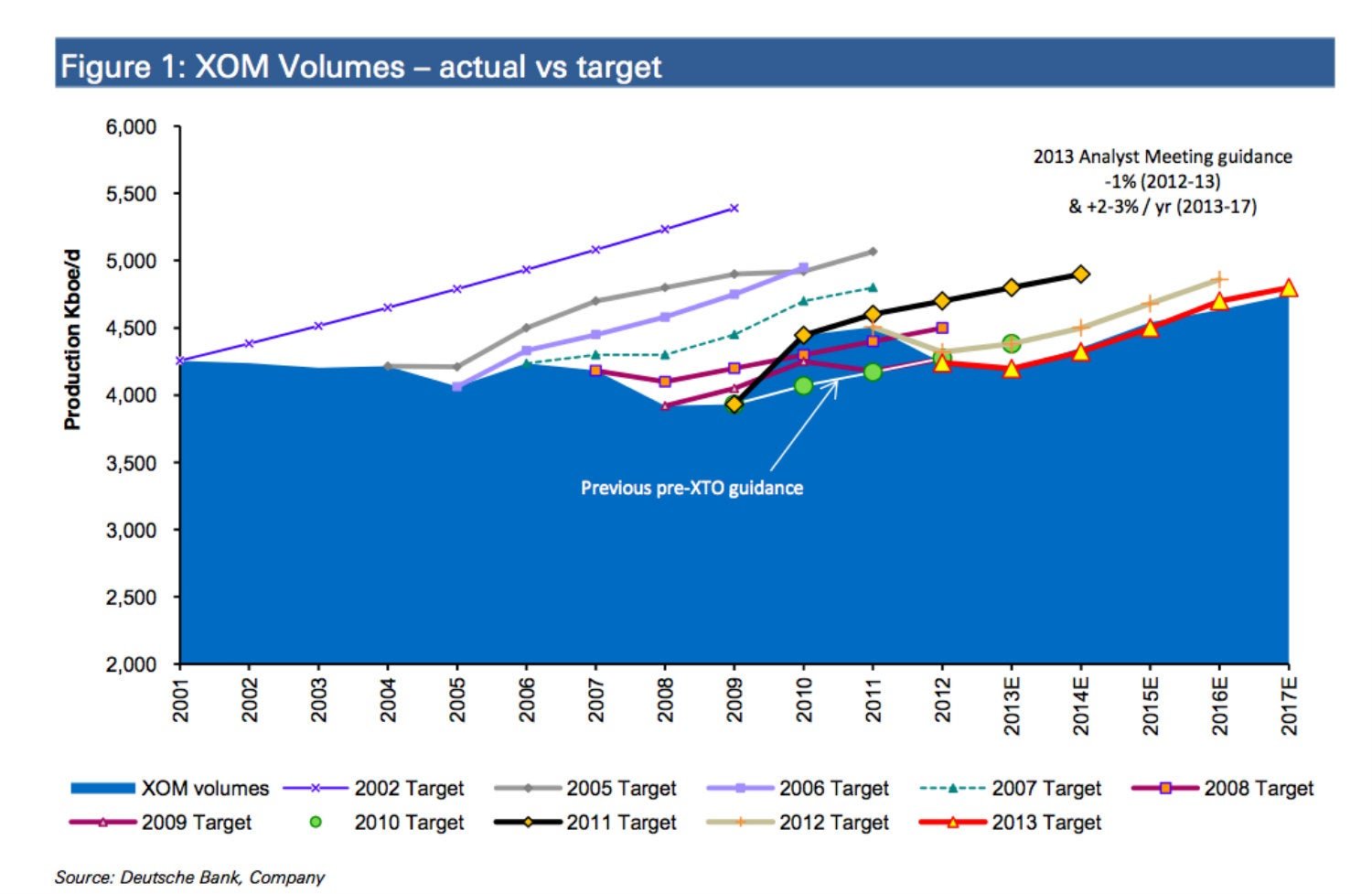

Yet for six years running, the company has fallen short of production guidelines provided to Wall Street analysts. Last year, its oil and gas production fell by 5.9% to an average of 4.2 million barrels of oil equivalent (boe) per day, double the 3% decline that it forecast. For 2011, the company projected a production increase of 3%-4%; instead its production rose by only 1%.

In retrospect, the company’s 2001 guidance sounds breathless. It said that production would rise to well over 5 million boe a day by 2009. Instead, that year it was about the same as in 2001—about 4.3 million boe a day. The chart below, provided by Paul Sankey at Deutsche Bank, shows how it revises its projections every year, and most of the time, falls short. (That bump after 2009 comes from its purchase of XTO, America’s largest natural gas producer.)

The main difficulty you usually face as a Big Oil company is maintaining or increasing your reserves base when, as ExxonMobil does, you pump 1.5 billion barrels of oil a year. But we are talking about a different challenge—capitalizing on the reserves already in your possession. With such a backlog of inventory, why can’t Exxon just turn on the tap?

I asked ExxonMobil, and got back this boilerplate: “Actual production in any specific year can vary above or below what is reflected in our outlook due to variables such as price, quotas, divestments, weather, regulatory changes, geopolitics and unplanned downtime in our operations as well as unplanned downtime in those properties that are operated by others.”

Wall Street analysts, however, say ExxonMobil’s problem is time and cost. That is, Exxon’s current reserves are not equivalent to those that it exploited two and three decades ago, but are deeper, more dangerous and far more expensive to produce. “Like your good looks, [the reserves] are there. It’s just a question of exploiting them. [But it’s] not that easy,” Sankey told me.

Oppenheimer’s Fadel Gheit estimated that, once ExxonMobil acquires reserves, it can now take as long as two decades to actually develop them. “It takes more spending and a longer time,” he told me. (The Financial Times has a good piece (paywall) on the problem of runaway costs.)

One conclusion is that when oil companies say they are achieving “full reserve replacement”—i.e., finding more new oil in a given year than they pumped, which is taken as a sign of their sustainability—it doesn’t mean quite the same as it used to. ExxonMobil, for instance, has announced 19 consecutive years of full reserve replacement, but if it is a substantial challenge to exploit those reserves, then they’re not contributing as much to the company’s financial value.

That is not news to ExxonMobil. So the question nags—if you’ve missed the target once, missed it twice, and know that it will be hard to meet the next one, why keep setting possibly embarrassing targets?

I do not have an answer to that. It could be something as simple as the share price—Exxon may not wish to walk back its production estimates to a more realistic projection of more or less 4 million barrels a day.

Stay tuned, though. This year, Exxon says its production will fall by 1%, and then rise by 2%-3% from next year through 2017. Let’s see if it’s becoming more realistic.