Inside the Global Times, China’s hawkish, belligerent state tabloid

Beijing

Beijing

Hong Kong’s best film of 2015 is a “virus of the mind.” Taiwan’s push for independence means war with China is inevitable. The international tribunal ruling on the South China Sea is a US-backed trap to discredit China. Australia is nothing but a “paper cat.” Donald Trump and Brexit prove Western democracy is dangerous.

China’s most belligerent tabloid, the Global Times, is certainly a one-of-a-kind publication. The Chinese- and English-language news outlet is published by the ruling Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) paramount mouthpiece, the People’s Daily, but it goes much further than China’s typically stodgy state news. The Global Times is best known for its hawkish, insulting editorials—aggressive attacks that get it noticed, and quoted, by foreign media around the world as the “voice” of Beijing, even as the party’s official statements are more circumspect.

That’s not exactly a mistake, the paper’s longtime editor says.

The Global Times often reflects what party officials are actually thinking, but can’t come out and say, editor-in-chief Hu Xijin explained during a long interview with Quartz in his drab Beijing office in the People’s Daily compound. As a former army officer and current party member, Hu said, he often hangs out with officials from the foreign ministry and the security department, and they share the same sentiments and values that his paper publishes. “They can’t speak willfully, but I can,” he said.

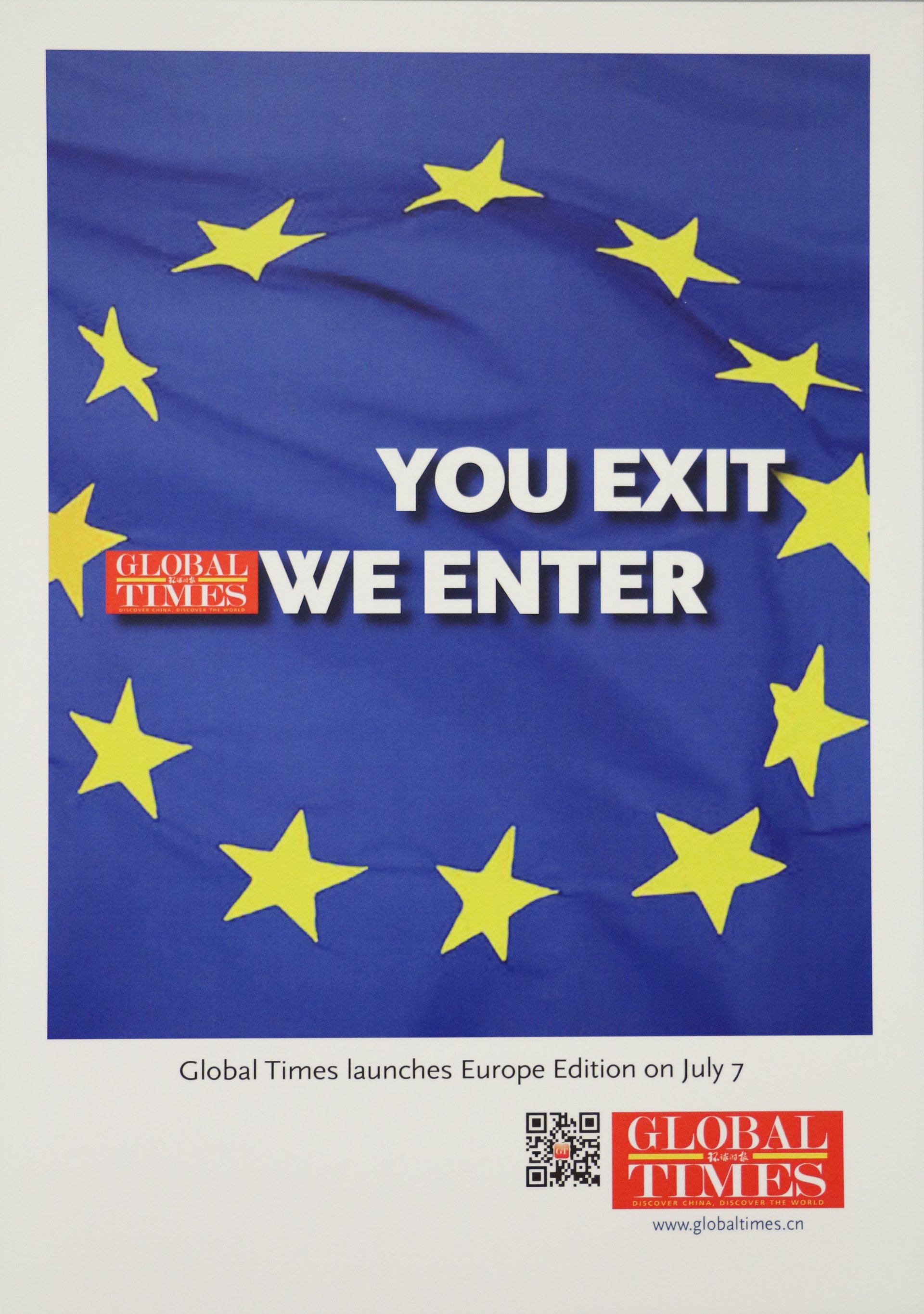

After starting in China, the Global Times has been expanding its footprint, bringing its unvarnished opinions around the globe. It rolled out a US edition in 2013, and a South Africa one in 2014. On July 7, the Global Times launched its Europe edition in a typically in-your-face manner—by mocking Britain’s Brexit, and Europe’s fears of China’s growing influence:

There are plenty of people who condemn the saber-rattling tone, both inside and outside China. But the Global Times’ importance as one tool to understand the growing nationalism in Beijing is undeniable, experts say. “Even if you don’t like it, you’ll probably have to read what it says,” said Zhan Jiang, a journalism professor at Beijing Foreign Studies University.

The evolution of the Global Times

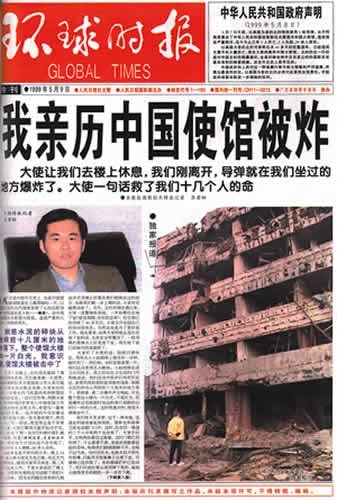

Founded in 1993 as a weekly magazine, the Global Times only became popular in China after it began selling Chinese pride rather than tidbits about political celebrities. In 1999, the Global Times reported from the front line the US bombing of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade, Yugoslavia. The US declared the incident an accident, but the Chinese public was outraged by the deaths of three citizens.

A special Global Times edition about the bombing sold 780,000 copies, almost double that of regular editions at the time, according to the Chinese magazine Phoenix Weekly (link in Chinese). The front-page story (link in Chinese) was an ambassador’s account of how he survived the bombing, which he called a “slaughtering” of Chinese people. “On May 9, the national flag at the Chinese embassy in Yugoslavia is still waving in the ruins,” the article ended. “Under the blue sky and against the backdrop of fire and smoke, the five-star red flag is very eye-catching.”

In 2001, after it covered the attacks on the World Trade Center in Manhattan, the Global Times’ daily circulation in China hit two million. In April 2009, it started an English-language paper and website, part of Beijing’s larger push to compete with foreign media and counteract what authorities believe is “biased” China coverage. Today the Chinese-language daily paper has a circulation of more than one million, and its English-language counterpart about 100,000. The Chinese-language website attracts 15 million visitors a day, Hu said.

The news outlet’s 700 staff work from the People’s Daily compound, a closely guarded development in Chaoyang, one of Beijing’s busiest districts. The Chinese-language newspaper’s operations are housed in 10-year-old low-rise offices. On the second floor, a digital screen welcomes visitors with the slogan: “Report on the diversified world, interpret complex China.” On the third floor a banner warns the editorial staff, “We must strive to open up but at the same time remain steady,” a nod to the self-censorship necessary for all state papers.

The operations of the English-language newspaper is a few blocks away, in a bright, spacious office that takes up an entire floor of the People’s Daily building. Chinese staff and a number of “foreign experts” share an open newsroom, overseen by jumbo versions of the paper’s iconic pages: the CCP’s 90th anniversary in 2011; the selection of Xi Jinping as the new party boss in 2012; an artistic full-page advert supporting Beijing’s South China Sea claim with the caption, “Our waters flow to our heart.”

While the Global Times reports on everything from politics to culture to sports, it is the editorial pages, shaped mostly by Hu, that attract global attention.

From Tiananmen protester to party faithful

Hu, 56, doesn’t write all the editorials himself, but he dictates his opinions to an editor who pulls things together, sometimes under the byline Shan Renping. The result is often blood-thirsty, and draws indignation from far corners of the globe.

On July 30, for example, the Global Times mocked Australia by calling it a “paper cat,” a play on Mao Zedong’s description of his Western opponents as “paper tigers.” Australia’s “inglorious history” is founded on “tears of the aboriginals” it said, responding to Australia’s support for a recent tribunal ruling that denied China’s South China Sea claims. “If Australia steps into the South China Sea waters,” it threatened, “it will be an ideal target for China to warn and strike.” Australian policy wonks were apoplectic. The Sun, an equally belligerent and prone-to-exaggeration tabloid in Britain, called it China’s “call to war.”

For Hu, it’s been a long journey from the idealistic young student he was in 1989, when he was a pro-democracy protester in Tiananmen Square, where a military crackdown ultimately killed hundreds or maybe thousands of protesters. Online discussions about the demonstrations are still censored in China today, and Chinese people refer to the crackdown simply by its date, June 4.

During the protests, Hu was at Tiananmen Square every day. He said he was “passionate” and “radical” at that time. But as a military man, he was also cautious to not be caught on camera (filming protestors is a common practice in China, so they can be tracked down later). He left the square before the crackdown, he said, adding “I don’t want to talk about the details.”

A Russian-language master’s student, he went right into journalism at the People’s Daily, covering the Bosnian War from Yugoslavia in the 1990s, and the Iraq War from the Persian Gulf in 2003. After nearly two decades with the parent paper, Hu was promoted to deputy editor-in-chief of the Global Times in 1996 and took over in 2005. Life in war zones changed him after his student days, he said. After witnessing the collapse of the Soviet Union and breakup of Yugoslavia after communism fell, Hu began to be concerned that China might also “lose control all of a sudden.”

“I saw the changes in the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia. Then I saw China’s development. It changed my mind,” he said. “I realized we were idealists in the past,” Hu said of the protests. “But the reality is different from our ideals.”

Selling patriotism or conspiracy?

The Global Times’ popularity in China has risen as Beijing has adopted a more outward-looking, aggressive foreign policy.

Loyal readers in China are mostly male, college-educated and with white-collar jobs, the paper says. They appear to appreciate the confident, China-first, mostly pro-government stance. Cheng Ming, 20, a finance student from Henan University of Economics and Law in central China, says the Global Times is one of the few Chinese news outlets that has “correct” values. “It always speaks the truth, refutes rumors, and slaps the face of public opinion leaders [who question the government],” he told Quartz. He pointed to a post last month (link in Chinese) refuting the rumors and accusations of government misconduct during the flooding in central China.

Critics inside China, though, say the news outlet is overly simplistic and potentially dangerous.

In one high-profile dressing down in April, Wu Jianmin, a former Chinese ambassador to France, called Hu ignorant of global affairs (paywall), and his columns extreme.

The tabloid creates sensation by selling “patriotic conspiracy theories,” argues senior journalist Chen Jibing. In the Global Times, “any critical remarks about China’s situation are full of vicious intentions of subversion,” Chen wrote in a column (link in Chinese) online. Instead of debating using facts, Hu always questions critics’ motives to “deliberately lead the discussion into a wrong direction,” Chen wrote. “The more popular the Global Times is, the more distorted Chinese people’s understanding of the society and the world is.”

It is also a defender of Xi Jinping’s crackdown on human rights activists in China, particularly when they’re foreign. Hu mocked the New York Times (link in Chinese) after it ran an interview with Peter Dahlin (paywall), a Swedish activist who was arrested and deported for running a human rights organization in China. ”Some Western media portray Dahlin as a positive figure,” he wrote. “They seem to think as long as a person causes troubles in China’s politics, or promotes Western values, whatever moves he takes are justified.”

Because China blocks the New York Times and numerous other foreign publications, many Global Times readers only know about Dahlin’s case from state media reports. (Dahlin worked with local lawyers to provide legal training and assistance for human rights advocates, and denied any wrongdoing after he was deported from China.) But readers embraced Hu’s theory of sinister foreign forces, and went even further in online comments under the editorials. “He should have been shot dead right after the arrest,” one wrote.

Hu realizes his anti-Western messages are sometimes overdone. “The West struggles with China’s ideology. Such a struggle has developed into a habit, a conditioned reflex,” he said. “They challenge us, and we criticize them. Both sides will inevitably make some inappropriate remarks.”

Patriot or Frisbee fetcher?

While a loyal group of readers may admire Hu, some of China’s internet users refer to him as a 叼飞盘的, or “Frisbee grabber,” an insult that basically means he’s a trainable dog that always fetches the Frisbees thrown by its master. Hu’s master, in this analogy, is the CCP.

In China the divided opinions about Hu and the Global Times reflects the broader divide between chest-thumping patriots and those who are more critical of Beijing. Because of this divide, the paper’s coverage sometimes becomes the subject of intense discussion.

One particularly controversial Global Times trope is Hu’s often-repeated theory of “complex China,” which essentially says China is too big not to make some mistakes. It is a lame excuse he trots out to explain away any Communist Party misconduct, Chinese critics say.

After railway minister Liu Zhijun stepped down for corruption in 2012, Hu wrote that (link in Chinese) “corruption cannot be ‘cured’ in any country—the key is to control it to an extent that is acceptable by the people.” Thousands of Chinese internet users weighed in on the post, many of whom believed he was whitewashing corruption.

Hu said he and his paper are serving Chinese citizens’ interests by “defending the state interests.”

“I believe the Communist Party’s fundamental interests are consistent with ordinary people’s interests,” he said. They have to be, he added, or the party can’t survive.

Still, he’s sometimes critical of the government as well. It should punch some holes in the Great Firewall (link in Chinese), he wrote on one Weibo post on his own account, and tear it down entirely in the future. In another post, he said China should have more free speech—censors deleted that one, he noted.

Hu said he will always defend free speech, even when he is the one being criticized. “So many people swear at me—and I take those remarks,” he said. “I hope the government could also take some.”

A final taboo

On the 20th anniversary of the 1989 Tiananmen Square incident, the Global Times’ English edition published a front-page story about the protests, breaching China’s official media silence on the bloody crackdown.

“It’s still a sensitive topic. Scholars, officials and businessmen declined interviews with the Global Times on the subject. And searches for ‘June 4 incident’ on the Chinese versions of Google, Baidu and Yahoo were blocked,” the article said. It is time to look at the bigger picture, a military expert told the paper.

Now “June 4” is no longer a sensitive topic on the Global Times, and Hu regularly comments on the incident when its anniversary comes. In May he wrote about (link in Chinese) the upcoming release of the last remaining jailed Tiananmen Square protester, but no other Chinese news outlet did. ”Life is very cruel sometimes—once you make a wrong bet against the history, your life is light as a feather,” Hu commented, describing the jailed protester as a long-forgotten nobody.

The Communist regime is opening up since he became the editor-in-chief 11 years ago, Hu said, and that’s why the Global Times has been making breakthroughs on sensitive issues. “We must adhere to press freedom and the party’s leadership at the same time,” he said.

Clearly, someone in Beijing thinks he’s doing that successfully.