Why the US’s pivot to Asia is about more than just China

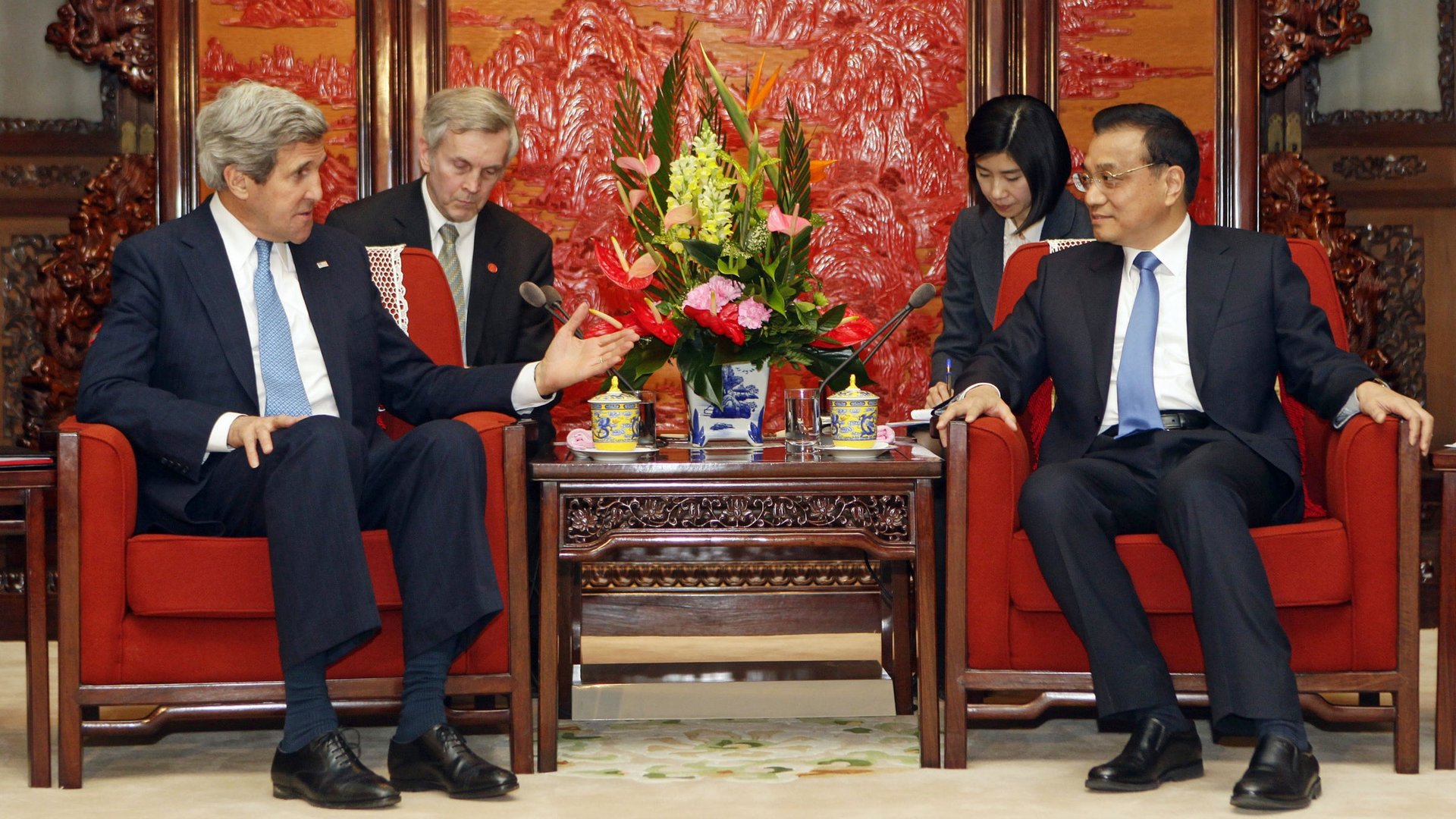

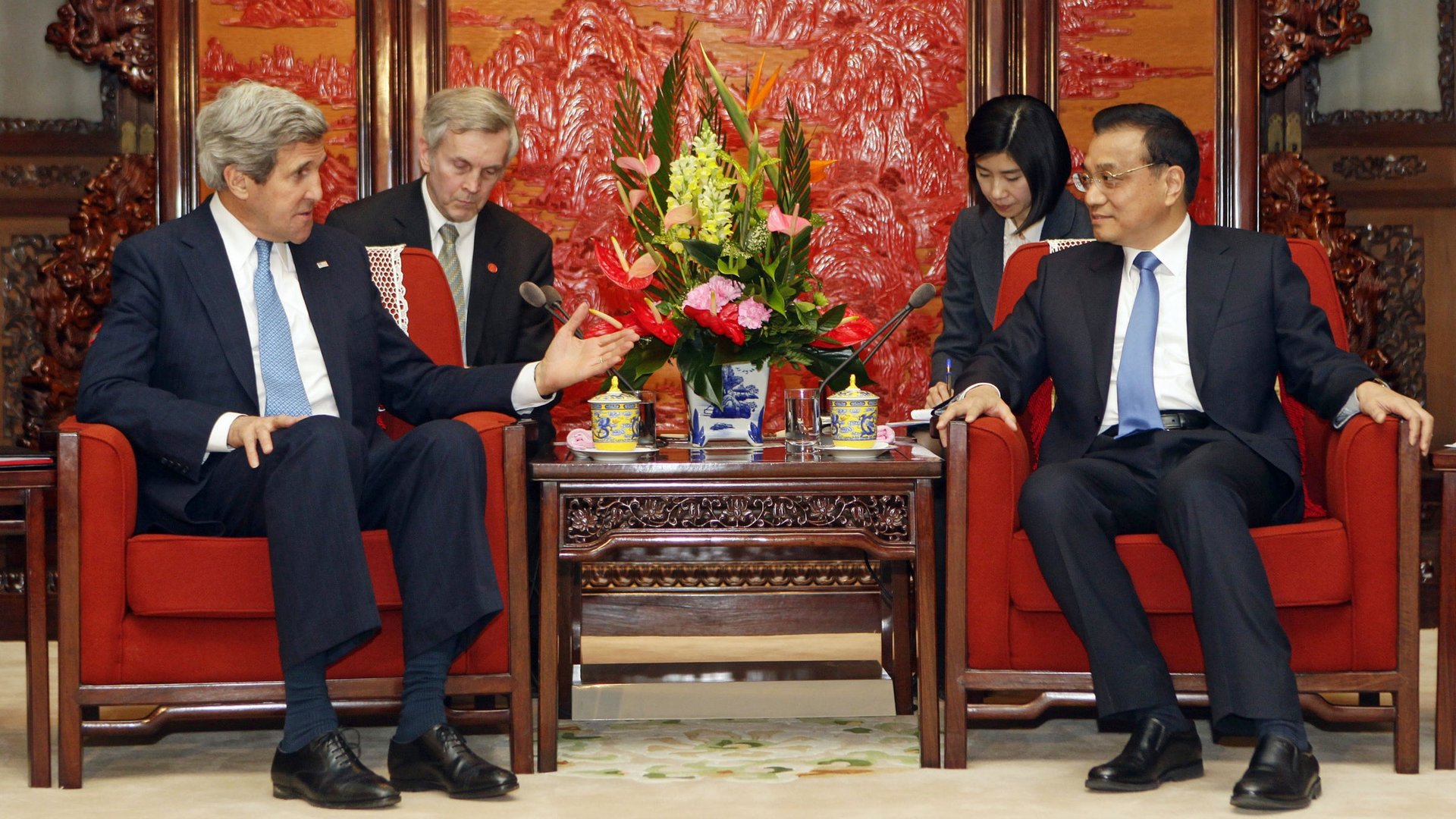

More than ten weeks after his confirmation as the new United States Secretary of State, John Kerry finally went to Asia. The former Massachusetts senator stopped in South Korea, Japan, and China over the busy weekend, the first time an American Secretary of State visited all three nations in the same trip. Kerry’s visit also coincided with the escalating crisis on the Korean Peninsula, a subject of increasing concern for Washington.

More than ten weeks after his confirmation as the new United States Secretary of State, John Kerry finally went to Asia. The former Massachusetts senator stopped in South Korea, Japan, and China over the busy weekend, the first time an American Secretary of State visited all three nations in the same trip. Kerry’s visit also coincided with the escalating crisis on the Korean Peninsula, a subject of increasing concern for Washington.

But zooming out a bit, Kerry’s visit also provides a fresh opportunity to examine the “Pivot to Asia”, one of the Obama Administration’s central foreign policy initiatives. Simply put, the pivot is meant to be a strategic “re-balancing” of U.S. interests from Europe and the Middle East toward East Asia. But what does that really mean, in practice? To further explore the “Pivot to Asia”, here’s a handy Q&A:

Why did the Obama Administration launch this pivot? And what does it entail, in practice?

Closer relations between the Washington and Asia aren’t new — trade between the continent and the United States, and between the U.S. and China in particular, has exploded in the past two decades, so in a way the “Pivot to Asia” is just placing a name on a trend that has been going on for years.

But there’s more to it than that. First, the Obama Administration wanted to signal that the Bush-era obsessions with the Middle East, democratization, and terrorism was over. The September 11th attacks and the subsequent occupations of Iraq and Afghanistan diverted Washington’s attention from an East Asia that had become, in the words of the Council on Foreign Relations’ Elizabeth Economy, an “economic center of gravity”. So, in short, the pivot made sense both in terms of domestic politics and international affairs — which is probably why it happened.

And what does it entail exactly?

So far, not much. The United States shifted 2,500 Marines to a base in northern Australia, a move that raised eyebrows in China, but otherwise Washington has taken very few concrete steps to match the pivot.

One issue that is worth watching, though, is the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). This is a free trade agreement that links a number of Asia-Pacific countries (including Japan, South Korea, Chile, and the United States) and represents one of Washington’s most ambitious trade proposals in years. On Friday, the U.S. and Japan concluded preparatory negotiations for the latter’s entry into the accord, signaling even closer economic engagement with Washington’s strongest traditional ally in the region.

In general, expect the United States to seek closer ties — both militarily and economically — in the years ahead with countries dotting the Pacific Rim. This is a win-win: For Washington, improving relations with established markets like Tokyo and Seoul and emerging ones like Jakarta and Manila presents tremendous opportunity, while for these countries the American presence acts as a check against growing Chinese power.

So this is about China, then, isn’t it?

Yes and no. Without question, China’s rise is The Big Story in East Asia, and Beijing has been throwing its weight around the neighborhood more in the past handful of years, from clashing with Japan over the Senkaku/Diaoyutai Islands to laying an expansive claim elsewhere in disputed maritime territory. The United States is the only country with enough muscle to check China’s rise, and many of the smaller countries in East Asia have sought reassurance from Washington that it remains invested in the region. It isn’t a coincidence, as Economy notes, that The Philippines allowed the U.S. to resume hostingmilitary forces at the Subic Bay base for the first time in almost 20 years.

But it’s important to remember that Asia is a very large place, and that American interests there go beyond the desire to manage China’s rise. Asia serves as the backdrop to many of the world’s most pressing issues, from nuclear proliferation to climate change, and remains indispensable to the functioning of the world economy. So while the rise of China is the single biggest causal explanation for the pivot, it’s far from the only one.

Is Secretary Kerry on board? And if not, is the pivot reversible?

During his confirmation hearings in January, Kerry famously expressed ambivalence about the pivot to Asia, leading some to speculate that he might wish to “unpivot” back to Europe and the Middle East. Though the Chinese would surely love it if Washington retreated from the region, this is unlikely: Kerry ultimately doesn’t call the shots in American foreign policy — Obama does. And Obama, according to Justin Logan of the Cato Institute, is a firm believer in the pivot: he even prefers the term to the more neutral “re-balancing” introduced as a softer touch by his administration.

But, as Logan cautions, second-term U.S. presidents have long been tempted by solving problems in the Middle East, particularly the Israel-Palestine crisis. And with the Syrian civil war, the Afghanistan pull-out, and a teetering Egypt, there’s certainly enough going on in the region to merit the administration’s attention.

Nevertheless, the “pivot to Asia” isn’t just whimsy — for all the trite sloganeering around the “Asian Century”, the continent will play an increasing role in American foreign policy going forward. So no- the pivot isn’t reversible, even as the rest of the world continues to matter, too.