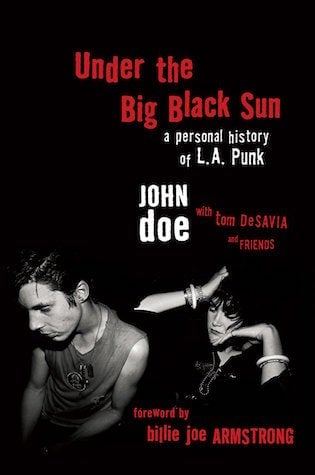

When your childhood hero becomes your collaborator—Tom DeSavia on co-writing a book on LA punk with X’s John Doe

“It took almost two decades, but he finally caved,” Tom DeSavia says of his unlikely collaborator, Los Angeles punk rocker John Doe, on the pair’s book, Under The Big Black Sun. “I felt like the story of the LA punk scene wasn’t being given its due, as opposed to the London and New York scenes, so I think the idea was there for a long time. But convincing John to actually tell the story was the key.”

“It took almost two decades, but he finally caved,” Tom DeSavia says of his unlikely collaborator, Los Angeles punk rocker John Doe, on the pair’s book, Under The Big Black Sun. “I felt like the story of the LA punk scene wasn’t being given its due, as opposed to the London and New York scenes, so I think the idea was there for a long time. But convincing John to actually tell the story was the key.”

For any author, the release of their first book is a monumental experience. But for DeSavia, it was a dream come true: A chance to tell the story of his much beloved (and under-appreciated) Los Angeles punk scene in collaboration with its godfather, Doe, of the seminal band X. The book includes contributions from a veritable who’s-who of punk virtuosos from the late 1970s and early 1980s, including Black Flag’s Henry Rollins, Jane Weidlen and Charlotte Caffey of the Go-Go’s, and former Minuteman Mike Watt, as well as an introduction from Green Day’s Billie Joe Armstrong about LA punk’s lasting impact. But it is the intertwining narrative between Doe and DeSavia that holds the book together and gives it heart and soul.

“There wouldn’t be a book without Tom,” Doe says of DeSavia. “We first met when he was working for X’s record label and was involved in putting together a box set of ours. We hit it off immediately, and after the project was finished, we became pals. But he was always asking me to tell him stories from the early days of the band, and I think in a way that was the beginnings of the book.”

DeSavia grew up a typical suburban Southern Californian kid in the 1970s, listening to pop radio and his family’s country records. He first saw X at 15.

“I had a flat top and my argyle sweater and was going to my first punk show,” DeSavia recalls. “I was thinking, ‘I’ll get a nice seat, eat some popcorn, and watch this band.’ I walked in there, and I was terrified. But I left feeling exhilarated, like I’d been in a speeding car that was going downhill for an hour towards oblivion. It went from fear to exhilaration. It was loud and dirty. And scary! I thought to myself, ‘I got out of there alive! I’ll never do that again!'”

But DeSavia was hooked. His record collection grew in leaps and bounds, full of albums from the burgeoning Los Angeles punk scene. X was always at the top of the pile.

DeSavia ended up working in the record industry. A pet project he insisted on marshaling was an X box set, which put him in contact with all the members of the band, including Doe. Once he’d connected with Doe professionally, their personal relationship developed, and DeSavia found himself at dinner or drinks, unable to keep the original fanboy inside him at bay.

“What I found, as our relationship developed,” DeSavia says, “is that there was the story everyone told—the legend, so to speak—but then there was the real story.

“I’d always prod John to tell me the real story behind the story—it was always crazier and funnier and greater then I ever could have imagined. And every time I’d tell him, ‘You’ve got to write a book someday.’ But he’d always shrug it off. Until, one day, he didn’t.”

“That was the key that opened the door,” Doe says of DeSavia’s idea to use the same collaborative approach that had marked the LA punk scene.

“I’d always told short stories that people—like my sweetheart and Tom—would encourage me to write down, and I think I was pretty good at telling them with all the little details that make stories compelling, but I just couldn’t fathom writing a whole book. But once we hit on the idea of a collaborative approach, with a lot of voices, even if they were contrary, or especially if they were contrary, then I saw the way forward.”

Doe’s essay on leaving the East Coast behind and heading for the sun-filled lifestyle he imagined was key. With a voice akin to that of Bob Dylan in Chronicles, or the best Charles Bukowski travelogues, it takes the reader immediately to the time and place.

“Most of my chapters were interstitial pieces, or at least that’s how I approached them, so as soon as I got the first sentence, it was onward,” Doe admits.

“I didn’t wring my hands about it. It was like writing a song or lyric: Whatever popped into my head would be the way forward. But I did think that telling the story of going West was the most important element to my story.”

“Honestly, I think it just clicked with him one day,” says DeSavia.

“I’m sure he was aware of the revisionist history that was going on. And once the concept of getting more voices than just his in there began to develop, he seemed to get kind of excited about it.”

So was he intimidated about working with his childhood hero?

“Nope,” DeSavia says flatly.

“By the point that we started working on the book, I felt really comfortable working with him. And that was a draw of this thing. I don’t think I could have even considered it if it felt like an unnatural collaboration in any way. But it sure was intimidating working with all these other folks from the scene that I only knew as a fan. In fact, I’m sure in the beginning, when John was emailing everyone asking if they’d contribute, they were like, ‘Who is this other guy?’ I would have. But everyone was great, really gracious. The sense of camaraderie that really marked the LA punk scene was still there and really spectacular.”

DeSavia says the writing was “pretty effortless,” and though the pair faced the daunting task of actually writing the book and making deadlines once a deal was in place, he insists the project came together naturally.

“It turns out—not surprisingly, really—that the story I wanted to know and the story John wanted to tell were really in line,” DeSavia says.

“The whole thing of us putting this together was walking blind into the publishing world. More than once we said to each other, ‘Okay, we know how to make records, but how do we do this?’ Plus, it hadn’t been done before, and we needed to not let it fall to revisionist history to tell this story, because that’s what was happening.”

Still, DeSavia did have to occasionally pinch himself.

“The 15 year old in me was definitely very present during this project, not just with John, but all the collaborators,” DeSavia confesses.

“There were some moments when I had to stop, take it all in, and—at the risk of sounding corny—feel really thankful and lucky. This era was so important to the development of everything I thought about art and music, and I still can’t believe we got a chance to document it in a way that people seem to be enjoying so much.”

Reviews and press about the book has been overwhelmingly positive, and sales have been brisk — it’s been an LA Times bestseller for the past six weeks. There’s also an amazing audiobook version that features all of the contributors reading their passages. So why was it so important to DeSavia to tell this story?

“The thing I hate most about the current American Idol culture of this country is the idea that music is a contest you win, where one person wins and everyone goes home,” DeSavia explains.

“The punk scene was the first thing that introduced me to going to a show where the bands would be telling you to go see other bands, being supportive of each other. That’s how I built my record collection. But that was really special to me, too.

“Also, lyrically the music spoke to us a lot when we were angry and frustrated, be it politically or with your life or not liking Journey, or any of those things that an adolescent goes through, be it poverty or not wanting to be wealthy, whatever. In that scene we all had something to rebel against, and this music spoke to it. And now, looking back, what gets me is that the message in the songs is timeless. They’re folk songs. And I think we’re at a time, not to get too political, when we need it again. We need to rebel against politics and the radio, and we need a soundtrack to it. I think this music is important for people to hear. We need it. So if the book reminds them that it’s out there and they rediscover it, or if it exposes a kid—or anyone—who didn’t know about the LA punk scene to it, and they discover the music and pick up a guitar, that would be great. Punk rock, at this point, is a philosophy. So I think this music coming back is absolutely crucial. The book shows it was absolutely about rebellion, and that it had a soundtrack. That was the part I loved about it: Teenage angst, frustration, and anger. So to carry that message with John was real important to me and a real honor.”

As we wrap up, DeSavia stops to make one last point; one that’s clearly significant to him in reflecting on his collaboration, but that also is important to that wide-eyed 15-year-old who discovered X in a dirty Los Angeles club all those years ago.

“One thing that didn’t strike me until we were finished,” he says, with a bit of amazement in his voice, “is that we didn’t come close to having one disagreement during the whole process.”