Parasites can change zebrafish behavior, and that could be a problem for medical researchers

For years, researchers have studied the behavior and genetics of the zebrafish in order to develop insight into human anxiety, depression, drug addition and other behavior disorders. But one scientist says that all those little animals might not have been acting of their own accord.

For years, researchers have studied the behavior and genetics of the zebrafish in order to develop insight into human anxiety, depression, drug addition and other behavior disorders. But one scientist says that all those little animals might not have been acting of their own accord.

Sean Spagnoli of Oregon State University recently published new research that suggests that in many cases, zebrafish are in part controlled by a parasite that can change the way the fish acts. If proven, it would mean having to rethink much of what we thought we learned about ourselves from the zebrafish.

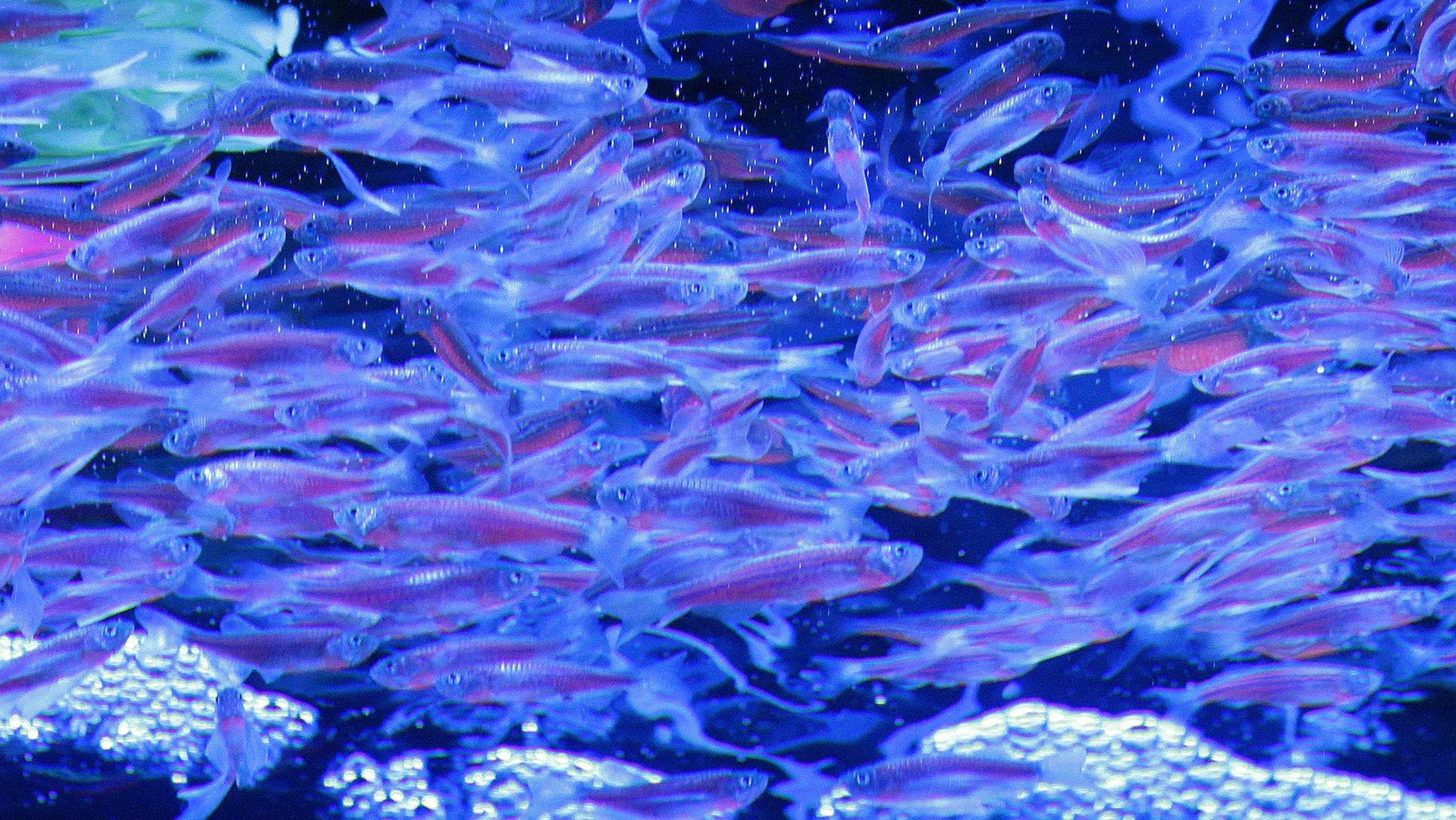

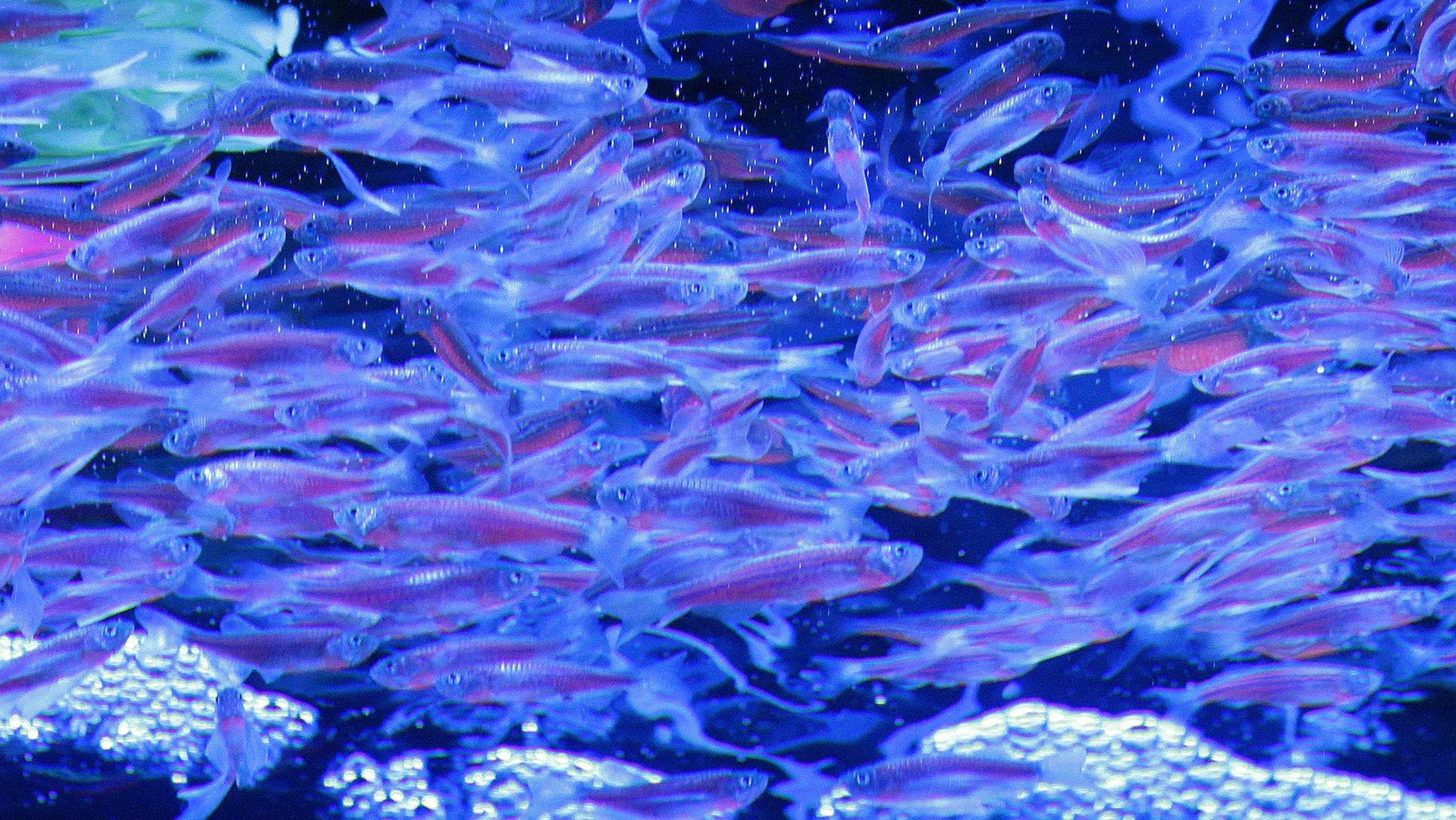

The zebrafish is a tiny freshwater-dwelling species, no more than a few inches in length. It’s a popular pet, but even more beloved by scientists who over the last 20 years have adopted the fish as one of the most popular experimental organisms for science. They’re easy to keep, grow quickly and tend to come in big batches—mothers can lay as many as 200 eggs a week.

Though it may seem weird that scientists are using fish as a means to understand people, as much as 70% of human genes are related to zebrafish genes. In addition, like humans, the zebrafish is a highly social animal, preferring to swim together in shoals. And their brains and behaviors seem as vulnerable to things like stress as us, with stressed fish seen lying at the bottom of the tank in a way researchers say resembles human mood disorders like depression. Since the 2000s, scientists have been studying the fish as models of autism, schizophrenia, and to see how they react to recreational drugs like ecstasy, for instance.

They use several methods, among them looking at how closely the fish swim together in shoals, and the startle response—how they react to a sudden surprise. For example, the more stressed the fish are, the closer they generally swim together. They’ve also been seen to stray behind the shoal when drunk on alcohol.

Spagnoli’s study, published in the Journal of Fish Diseases, argues that these behaviors also change when zebrafish are infected by a parasite called Pseudoloma neurophilia that attaches to the central nervous system and whose spores are both difficult to detect and stubbornly resistant to the standard measures used to keep fish clean. Spagnoli’s team found that infected zebrafish swam closer together and also took longer to get used to the distraction of persistent tapping on the side of the tank. Given how researchers take these as signs of all kinds of things, from reaction to drugs to anxiety, it’s worrying if, even just sometimes, they were actually just being controlled by a bug.

There’s no telling yet how much this may have affected previous studies, and it’s unclear how widespread the problem is. Spagnoli told told Nature that between 7-10% of a laboratory’s fish may be infected. In 2015, nearly half of the 28 laboratories that sent their fish (pdf) to the Zebrafish International Resource Center in Oregon—which supplies zebrafish for scientific use and diagnoses those with disease—had cases of P. neurophilia.

Other scientists are skeptical. They cite weaknesses in the study’s methods—comparing screenshots rather than automated computer tracking to work out the distances between fish, for instance. Jason Rihel, a biologist at University College London says the paper contains very basic statistical errors that make it hard to tell if what Spagnoli found was real or not. “I wouldn’t exactly be surprised if parasites have an effect on behavior,” he told Quartz, “It is just that this paper does not show it, and so there is no story here.”

Will Norton, who works with zebrafish at the University of Leicester, concurs. “This is an interesting study,” he told Quartz. “However I don’t think it raises a serious concern for other behavioral experiments in zebrafish.”

Other researchers told Nature that the infection is known and that some labs have already implemented improved screening for the parasite. But Spagnoli, who is investigating other infections that may have similar effects, says it still raises a huge red flag on what has become an important tool for behavior science.