Being killed by stray bullets is a real hazard in Rio, and it’s getting worse

University student Arthur de Barros Marques was riding his motorbike home from class when the fatal bullet found him. Sônia Maria Borges de Freitas, a cautious retiree who avoided back streets, was cut down by a gun blast just around the corner from her home. Five-year-old Ana Beatriz Duarte was felled during an outdoor party. Her family thought she’d simply lost her footing, until emergency room doctors found a 7.62 mm slug in her skull.

University student Arthur de Barros Marques was riding his motorbike home from class when the fatal bullet found him. Sônia Maria Borges de Freitas, a cautious retiree who avoided back streets, was cut down by a gun blast just around the corner from her home. Five-year-old Ana Beatriz Duarte was felled during an outdoor party. Her family thought she’d simply lost her footing, until emergency room doctors found a 7.62 mm slug in her skull.

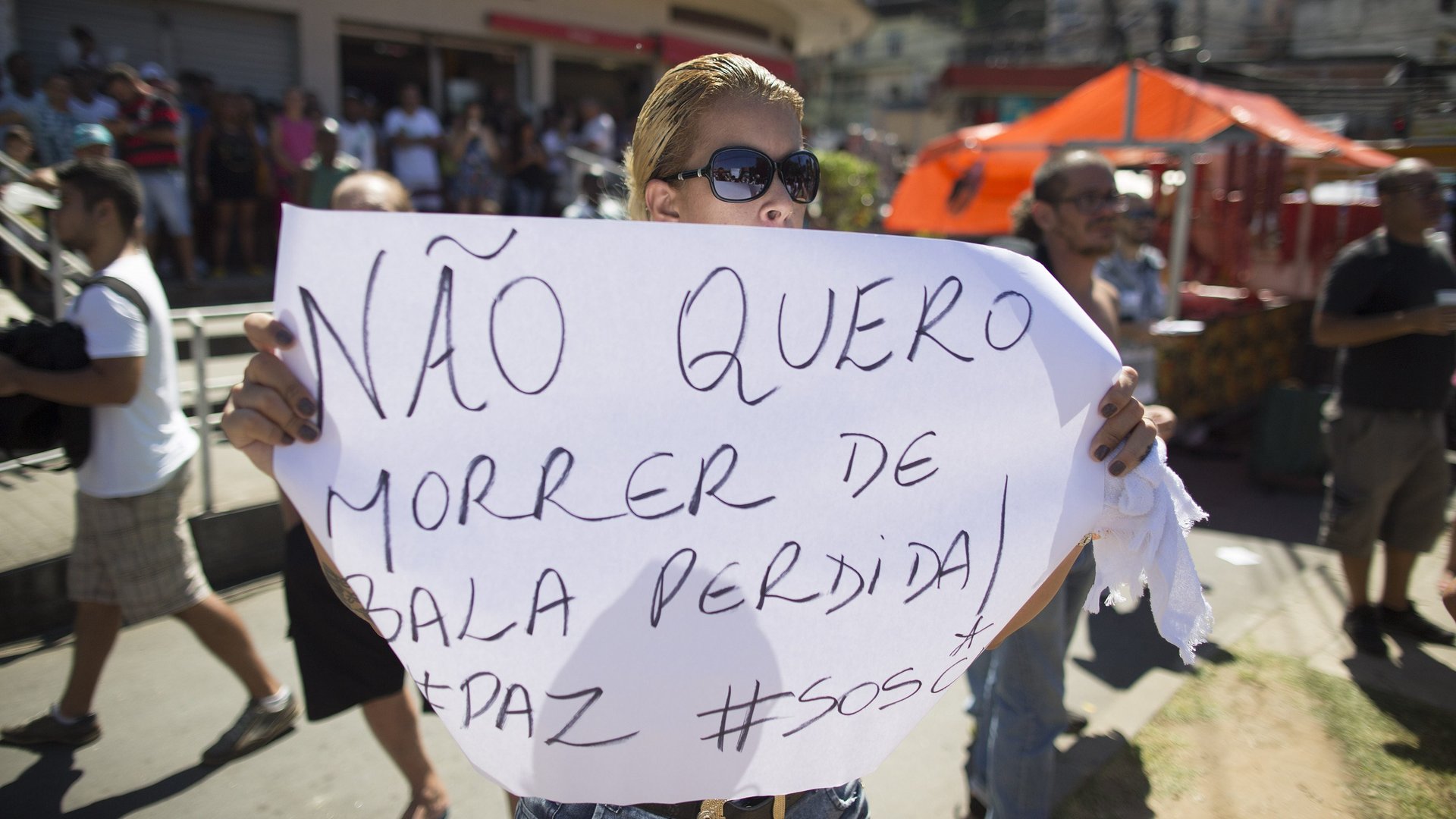

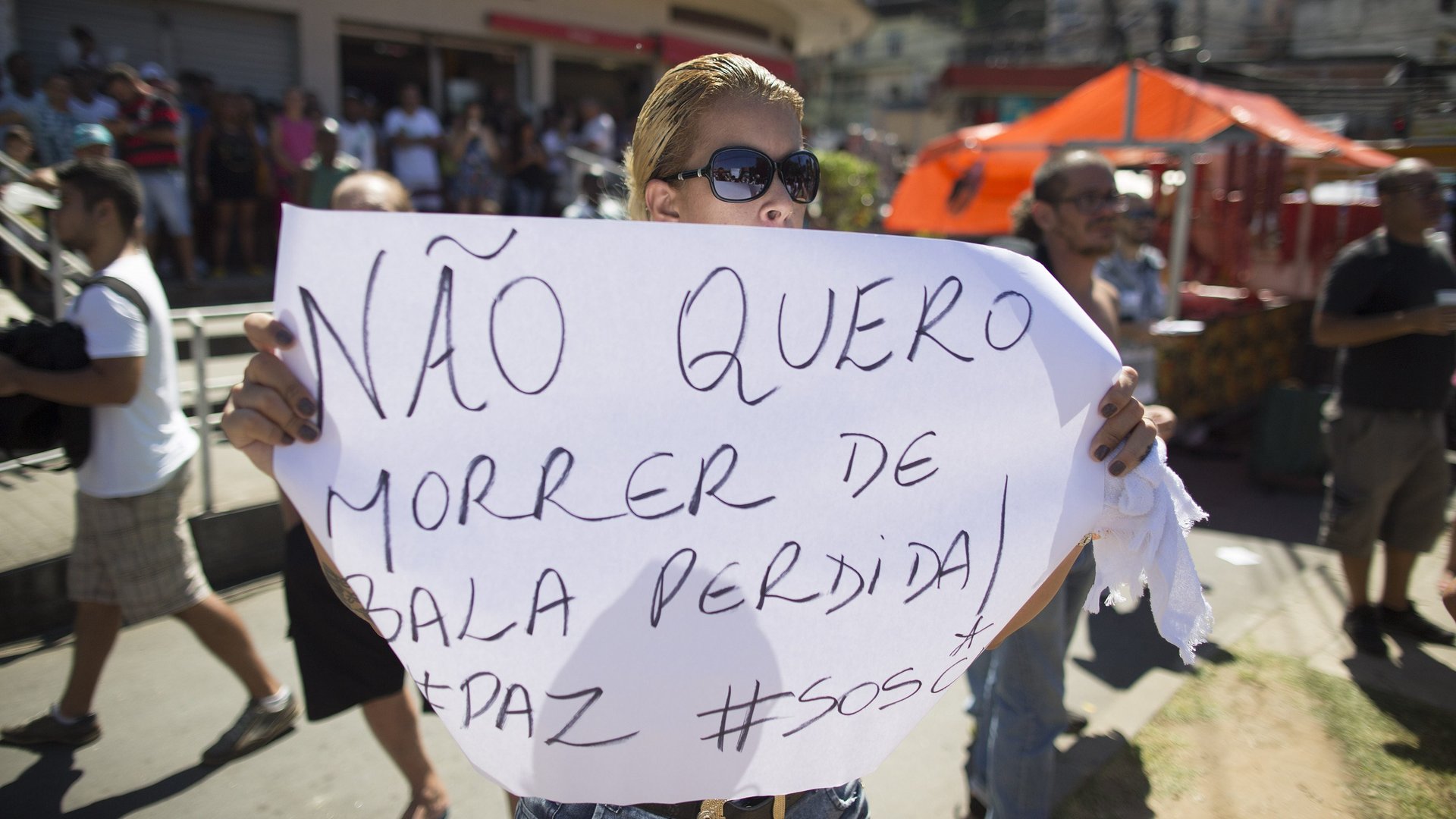

All three were victims of balas perdidas, or stray bullets—the crossfire between police and drug traffickers, or between rival gangs of traffickers, that ends up hitting common citizens. As Rio de Janeiro girds for the Olympics, they’re becoming more prevalent.

The Radio BandNews network had tallied 125 stray bullet victims (Editor’s note: all links in Portuguese), 33 of them fatal, in and around Rio by mid-July of this year, as against 95 the whole of last year. (The state government hasn’t published statistics on stray bullet victims since 2013; a spokeswoman said it’s revising its methodology, after complaints of undercounting.) In one 72-hour period in mid-July, balas perdidas left four dead and three injured. Among the dead was 25-year-old Vanderson Lessa, a paraplegic who was unable to maneuver his wheelchair out of the line of fire when a street party degenerated into fire fight between criminals and police. Lessa had been confined to the chair after getting shot while being held up five years earlier.

Rio had made progress against violent crime in recent years, but there was a 17% increase in homicides and 34% surge in street robberies in the state during the first six months of this year, government statistics show. Called before Rio’s state parliament to explain, José Mariano Beltrame, the state’s public security minister, put the blame on the crisis engulfing its oil-based economy.

Rio’s governor recently declared “a state of public calamity” and law-enforcement officers are suffering the consequences, he said. Some police have gone weeks without pay. There hasn’t been enough money to put gasoline in patrol cars, or printer ink to print arrest warrants. Law-enforcement officials told me they are facing conditions similar to war. More than 60 police have been killed in the line of duty in the state so far this year.

The police’s role in many stray bullet killings has provoked criticism from human-rights activists and even a judge. In a court order to halt night-time police operations in one favela after a stray bullet incident, judge Angélica dos Santos Costa wrote “It’s unacceptable that the police, in the 21st century, can’t find a way to confront crime without exposing the law-abiding citizen [to danger].”

But Beltrame, the public security minister, seemed resigned to stray bullets. “Historically, that’s the way Rio is, unfortunately,” he said.

Historically those at highest risk of being hit by balas perdidas have been Brazilians living in or near Rio’s favelas (shantytowns). But there have been signs this year that random shootings are spreading to other areas. After a recent battle between police and criminals in a comfortable northern suburb, Brazil’s Olympic sailing coach, Torben Grael, came out to find a bullet hole in his garage door. “It was only a scare, but for how much longer?” he told Brazilian reporters. “This never used to happen, but there are shootouts all the time.”

Stray bullet killings have created searing scenes that capture the chaos of a city that has sometimes seemed at the point of unraveling. In June, Carlos Eduardo Nogueira da Silva, 20, got hit by a stray bullet while standing in a doorway drinking coconut water from a shell.

His mother, Sheila Cristina, with her son’s blood streaked across her face, demanded justice on television—but amid the social and economic breakdown of Rio, she had trouble even claiming the corpse. Rio’s main forensic medicine center was shut down because the government lacked funds to ensure minimum standards of hygiene. Da Silva’s family spent four days searching morgues for the body, and had to pass the hat around the neighborhood to pay for the funeral.

The fear of walking into a crossfire permeates the subconscious of many Rio residents. “I only want to know when it will be my turn,” a Rio rapper, Gabriel the Thinker, wrote in a song titled, plainly enough, “Bala Perdida.” “Where will it be? At the circus, on the beach, at the supermarket, at a table in the bar?”

Stories of near misses make a big splash in the media, conferring a fleeting celebrity on their protagonists. Last year, a fashion designer said she was saved by a handbag that swallowed up a round from a .22. Before that, a motorcyclist said a Bible he kept in the storage box had blocked a bala.

Beleaguered Rio residents try to take hope where they can find it. In June, locals became fixated on the condition of a four-legged victim of bala—a mutt named Sheik. Found hobbling around with a bullet wound in his leg, Sheik was taken to a veterinarian by an animal protection group. It was touch-and-go whether the leg would be amputated, and the local media reported every change in his condition.

(Sheik wasn’t the first member of the animal kingdom to become locally famous after taking a random bullet. In 2002 a tortoise was hit in his hind legs by a bala; vets attached wheels to his underside to give him some mobility.)

In the end, Sheik pulled through with his leg intact. It was the sort of happy ending Rio residents haven’t had much of lately.