If millennials truly want to start a political revolution, they’ll need to vote

For the first time, the number of millennials eligible to vote (69.2 million) in the presidential election will be nearly equal to the number of Baby Boomers (69.7 million), according to a Pew Research Center analysis of US Census Bureau data.

For the first time, the number of millennials eligible to vote (69.2 million) in the presidential election will be nearly equal to the number of Baby Boomers (69.7 million), according to a Pew Research Center analysis of US Census Bureau data.

Yet, despite media predictions that the millennial vote will rise this election year, some experts are more skeptical. As evidence, they point to years of historical data showing younger Americans vote at much lower rates than older Americans, and are generally less engaged in the political process. Although millennials and Baby Boomers make up equal proportions of the US voting-age population (about 31%), Baby Boomers are much more likely to actually go to the polls on election day.

That’s the thing about democracy—social media outrage only goes so far. And while some politicians—notably Bernie Sanders—were able to garner enthusiastic and pointedly youthful crowds during the primary, appearances can be deceiving. Historically, young voters in the United States have been equally remiss about exercising their right to vote. Since 1964, young voters ages 18 to 24 have consistently voted at lower rates than all other age groups, according to a 2014 US Census Bureau report, “Young-Adult Voting: An Analysis of Presidential Elections, 1964-2012.” Meanwhile, older voters have consistently voted at much higher rates. In fact, since 1986, Americans 65 years or older have voted at higher rates than any other age group, according to a 2015 Census Bureau report, “Who Votes? Congressional Elections and the American Electorate: 1978-2014.”

These voting patterns have been consistent regardless of whether it is midterm or a presidential election, says Thom File, a sociologist at the Census Bureau and author of both reports.

Indeed, any talk of massive voter shifts is pure conjecture, says Zoltan L. Hajnal, professor of political science at University of California, San Diego. Even US president Obama, who was a highly popular candidate going into his first election in 2008, experienced only a slight increase in youthful support. Across the board in 2008, voters age 18 to 24 were still the least likely to go to the polls.

“I have not seen anybody providing numbers showing an extraordinary number of young voters,” Hajnal says. Most of the reporting is anecdotal, he says, based on discussions with individual millennial voters.

Part of this disconnect may have to do with our transition into a digital-first reality. With the popularity of Twitter, Snapchat, Instagram, and Facebook, making one’s opinion heard is easier than ever. For millennials, casting a ballot is only one of many ways millennials feel comfortable expressing their views.

In fact, despite voter registration programs aimed specifically at millennials, America’s youngest voters have actually become less engagement over time, as 18- to 24-year-olds’ voting rates dropped from 50.9% in 1964 to 38% in 2012, according to a 2014 Census report.

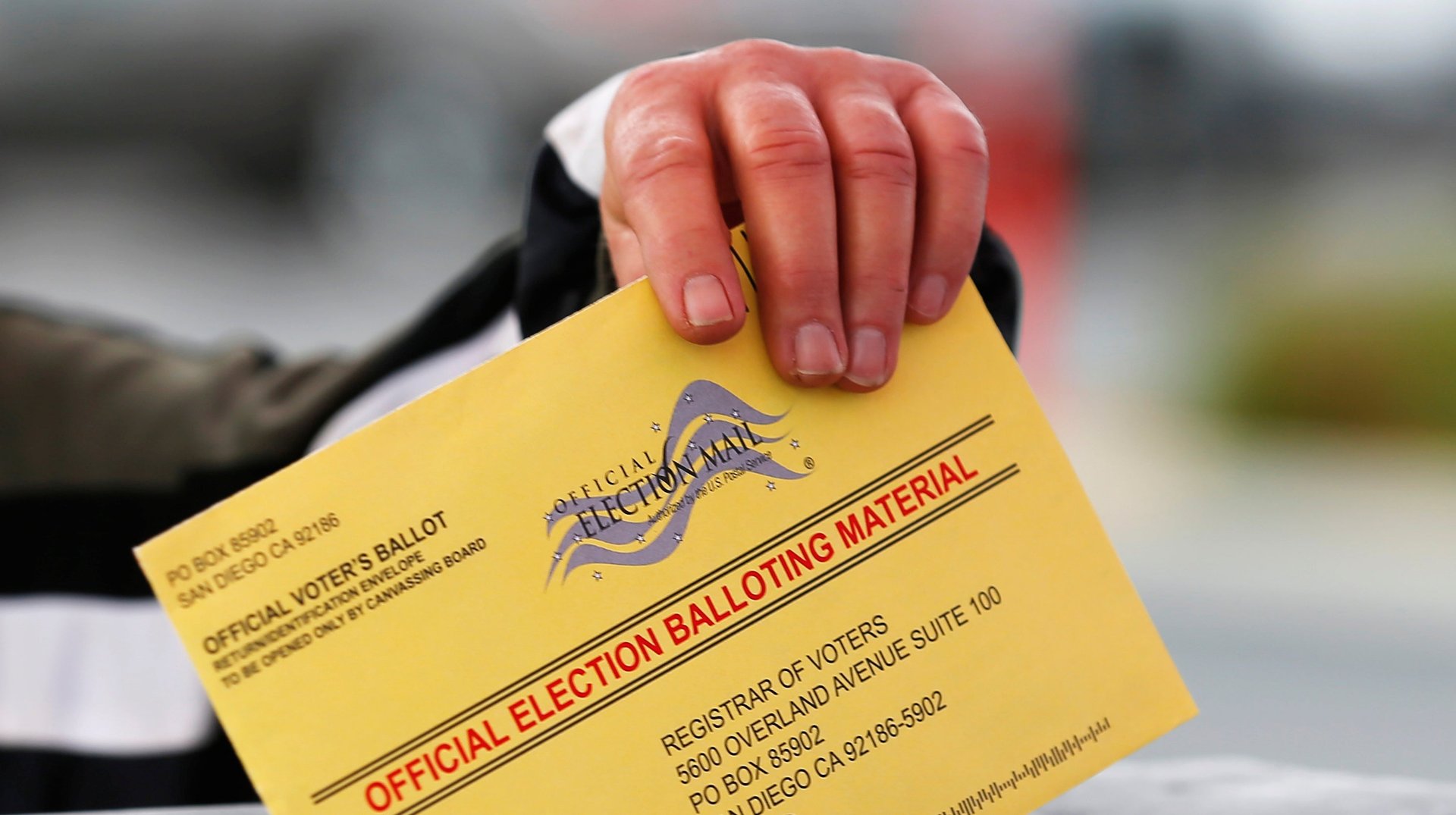

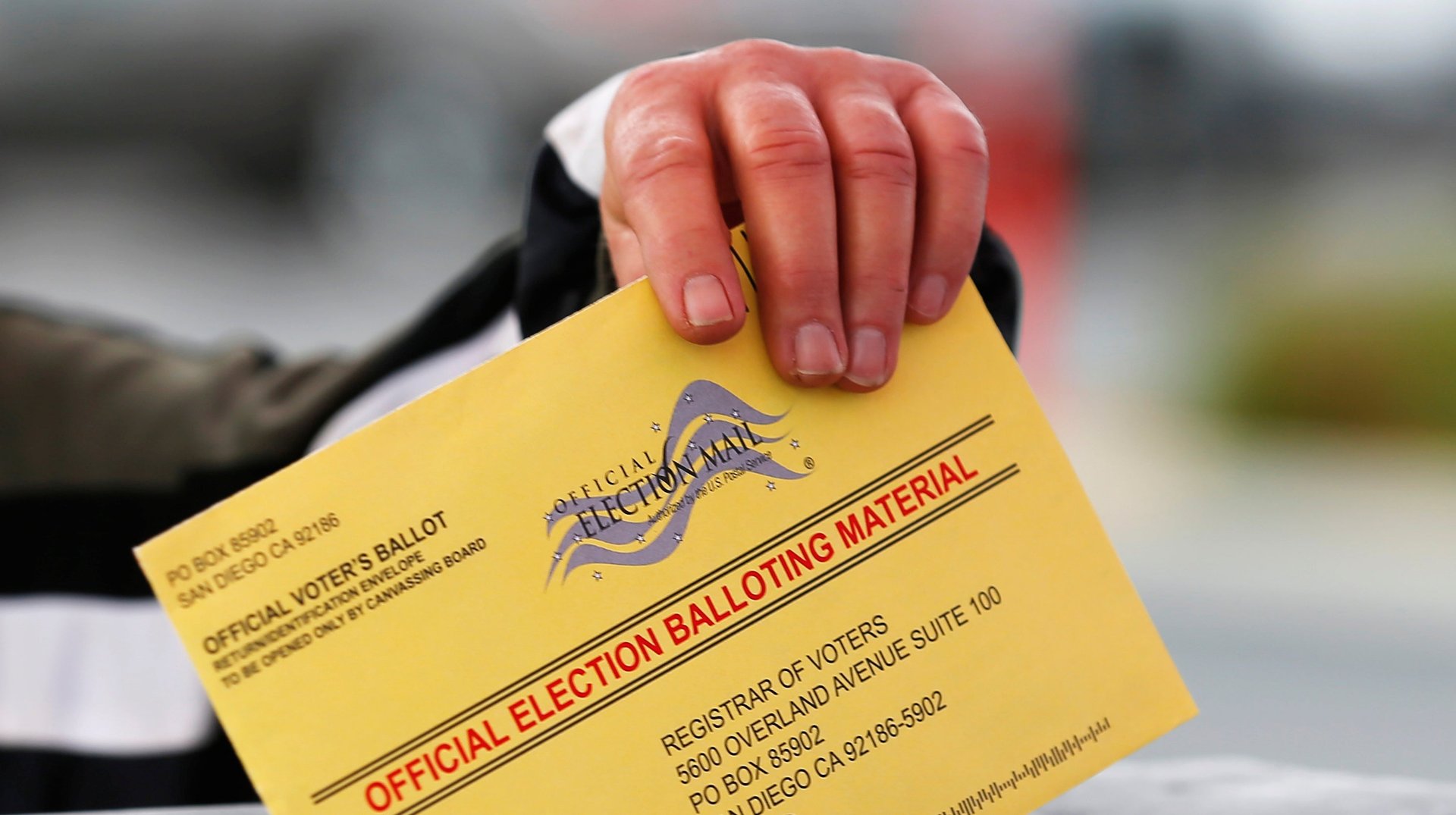

The problem is forcing some voting advocates to get creative. Matt Singer, founder of National Voter Registration Day, has been working to publicize a national holiday devoted to registering new voters, celebrated on the fourth Tuesday in September since 2012. While you won’t get the day off from work, the White House and the National Association of Secretaries of State both recognize National Voter Registration Day as an official holiday.

“We’re on track for record millennial engagement this fall,” says Singer, himself a millennial.

Social and geographical mobility is another reason young people may end up missing elections, according to political science professor Hajnal. If a voter moves to a new county or state, they need to re-register to vote. Even if they move within their existing county, they still need to complete a new voter registration form to update their address. Just starting out professionally, younger voters are more likely to move between communities.

Not surprisingly, the 2015 Census Bureau report finds that voting rates are highest among those with advanced degrees (62%), those who had lived in their current home for 5 years or longer (57.2%) and those living in households making over $150,000 in family income (56.6%).

At the same time, issues such as property tax reform, entitlement programs, and health-care benefits can lend a sense of urgency to elections for older voters thinking about the immediate future.

Preferred news sources may also influence political engagement, especially at the local level. People who read the news are more likely to participate in the political process, according to Danny Hayes, associate professor of political science at George Washington University.

We don’t totally understand whether political engagement drives interest in the news or if interest in news drives political engagement. However, the fact that millennials are more likely to get their political news from social media and national news sites like BuzzFeed or Huffington Post means they’re also less likely to feel engaged in the minutiae of their counties and municipalities.

Millennials aren’t digging deep, says Skylar Werde, strategic venture director at BridgeWorks, a generational consulting company. They are looking for the top 10 things they need to know and moving on. “None of these news sites are talking about how to be engaged in the local community,” he says, “so they are going to miss that piece of the conversation.”

And as voters who lived through the Al Gore/George W. Bush debacle remember, every little bit of engagement helps.