Central banks are printing money as though the global economy is in freefall

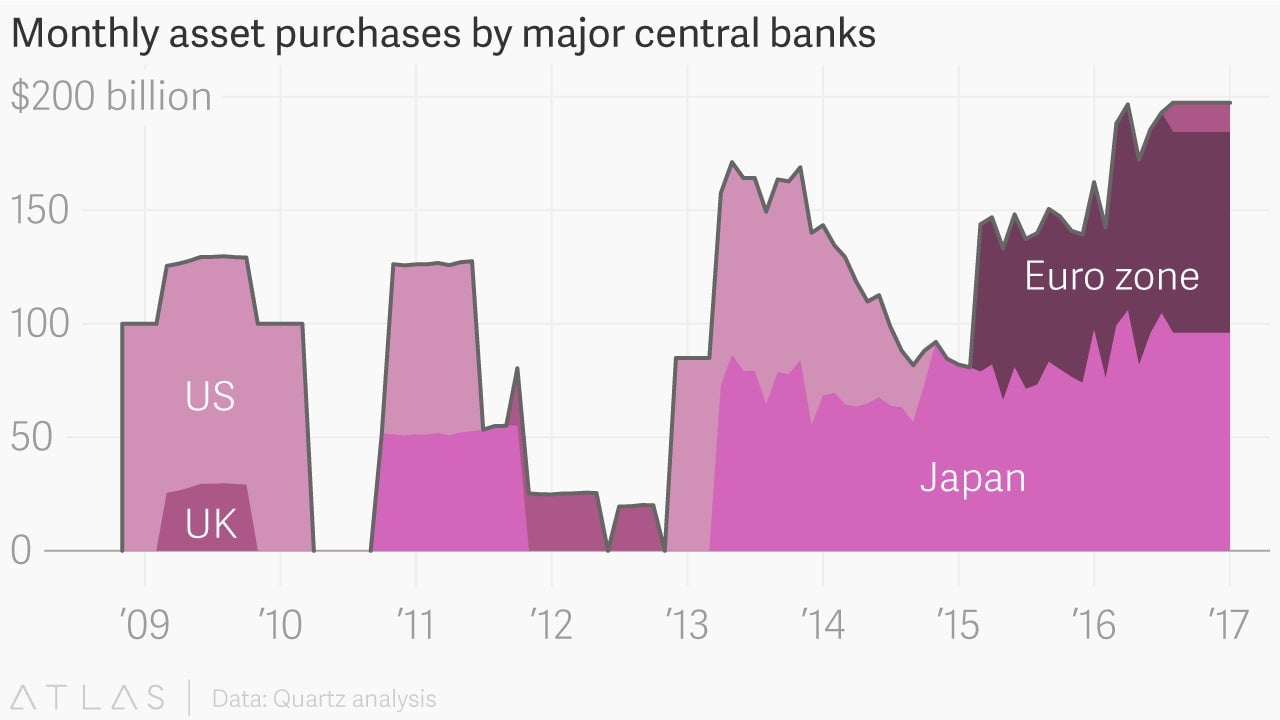

Central banks around the world are now spending $200 billion a month on emergency economic stimulus measures, pumping this money into their economies by buying bonds. The current pace of purchases is higher than ever before, even during the depths of the financial crisis in 2009.

Central banks around the world are now spending $200 billion a month on emergency economic stimulus measures, pumping this money into their economies by buying bonds. The current pace of purchases is higher than ever before, even during the depths of the financial crisis in 2009.

And yet, despite the extraordinary support of so-called quantitative easing (QE), the global economy is not in great shape. What was supposed to bolster economies temporarily during times of crisis has become a routine tool for policymakers, who long ago cut interest rates to zero (or below) but haven’t seen the pick-up in activity they would have hoped.

Alberto Gallo, a fund manager at Algebris Investments, says we are in a state of “QE infinity” with persistently low growth, low interest rates, and central bank policies that don’t fix things.

“They won’t ever say they’re out of ammunition, but central bankers are starting to look like naked emperors,” Gallo wrote in an article for the World Economic Forum.

The criticism central banks face for enacting these policies—that many argue increases inequality—is getting more heated. Meanwhile, governments are accused of not doing their part, leaving central bankers do all the heavy lifting.

The Bank of Japan and the European Central Bank are the biggest contributors to the current bond-buying spree, at about 10 trillion yen ($96 billion) and €80 billion ($88 billion) a month, respectively. The Bank of England said last week that it was getting back in the QE game, fearing the economic consequences of the Brexit vote. It will add £60 billion ($78 billion) to its stock of government bonds over the next six months, and is also buying £10 billion of corporate debt for good measure.

Over and over again, central bankers say that their stimulus measures only buy governments time to enact more durable reforms. But we shouldn’t expect a burst of fiscal stimulus from elected officials anytime soon, JPMorgan analysts warn in a recent research note. In fact, fiscal policy will act as a drag on growth into next year, they say. This was also the case between 2010 and 2015, when government policies to tighten spending dampened global GDP, working against the monetary stimulus provided by central banks revving their printing presses.

Jörg Krämer, chief economist at Commerzbank, says that the ECB’s bond-buying program has allowed governments to gloss over the root causes (pdf) of the region’s financial malaise, artificially boosting asset prices across the euro zone. Specifically, QE has pushed down yields on government bonds so nations can borrow for less than ever before, removing any sense of urgency about restructuring and reforms.

After years of QE, central banks already own much of their nations’ debt, a problem in itself. This week, just two days into the Bank of England’s latest round of bond buying, it ran into trouble after not getting enough offers from holders to sell the securities it was looking to purchase. This raises questions about the effectiveness of these policies, if central banks can no longer convince the market to give up their holdings even when offered above-market prices.