“I’m talking about the greatest tool ever”: The story behind the first Mac, and the social web Steve Jobs predicted years before it existed

Steve Jobs came to Newsweek in early 1984 wearing a sharp suit and a tiny bow tie. He was 28 years old. He met with top editors, we Wallendas—a self-important reference to the aerial circus act—and our owner, Kay Graham, up from Washington for her weekly visit. For two hours Steve showed off the first Macintosh computer, flirting with Kay and teaching us how to manipulate the mouse and switch disks to launch applications and save work. I remember someone asking, “Why call it a mouse?”

Steve Jobs came to Newsweek in early 1984 wearing a sharp suit and a tiny bow tie. He was 28 years old. He met with top editors, we Wallendas—a self-important reference to the aerial circus act—and our owner, Kay Graham, up from Washington for her weekly visit. For two hours Steve showed off the first Macintosh computer, flirting with Kay and teaching us how to manipulate the mouse and switch disks to launch applications and save work. I remember someone asking, “Why call it a mouse?”

Not long after, I had dinner with Jobs and Washington Post writer Tom Zito at Tiro a Segno, a private club in the West Village that had a shooting gallery in the basement. Zito’s father was the club president, and Tom showed us around. The rifles in the basement were very old, the targets elegant. There were murals of Capri in the handsome dining room and the maître d’ looked like the dapper Argentine actor Fernando Lamas. Zito and I had dates, but Steve came alone.

When we sat down, Zito ordered a round of Negronis. It was a long way from Steve’s hometown of Cupertino, and he was circumspect, but Zito put him at ease with leading questions that let him show off without seeming arrogant. Dinner became an interview as Zito drew Steve out, and everyone’s enthusiasm mounted for his many ideas. He didn’t seem to notice, but I could see that the women found him attractive, even though he was at least 10 years younger than they were. In fact, they were very interested. Maybe they would even buy one of his intriguing new computers. That, he noticed.

“What are they called?” one of the women asked. “Macintosh,” Steve said.

“Like the apple?”

Steve said his dream was that every person in the world would have his or her own Apple computer.

“That’s going to be all about marketing,” Zito said.

“I know,” Steve said. “But I’m talking about the greatest tool ever.” He went on about how people were going to shop on his computers, and keep their own libraries, and even send messages to each other.

“What a great appliance,” I said. He was just so serious. “Yes, but don’t call it that,” he said. “Bad marketing.”

We all nodded and Steve said he had to stay focused and pay attention to everything, marketing of course, and all the other details beyond the engineering, even the typography. The design had to have soul. If you got it right, a personal computer could be not only the best tool ever but fun, “like a bicycle for your mind”—he had come up with this after reading a Scientific American article on locomotion efficiency and was beginning to use it with reporters.

“That’s good marketing,” Zito said.

I told Steve that maybe Newsweek could do a special issue about everything he was talking about—how computers were going to change the way we lived. It couldn’t be just about him and his Macintosh, but he would be a big part of it.

“Okay,” he said, but then explained that he didn’t have much confidence in journalists getting his story right. I said I could understand that.

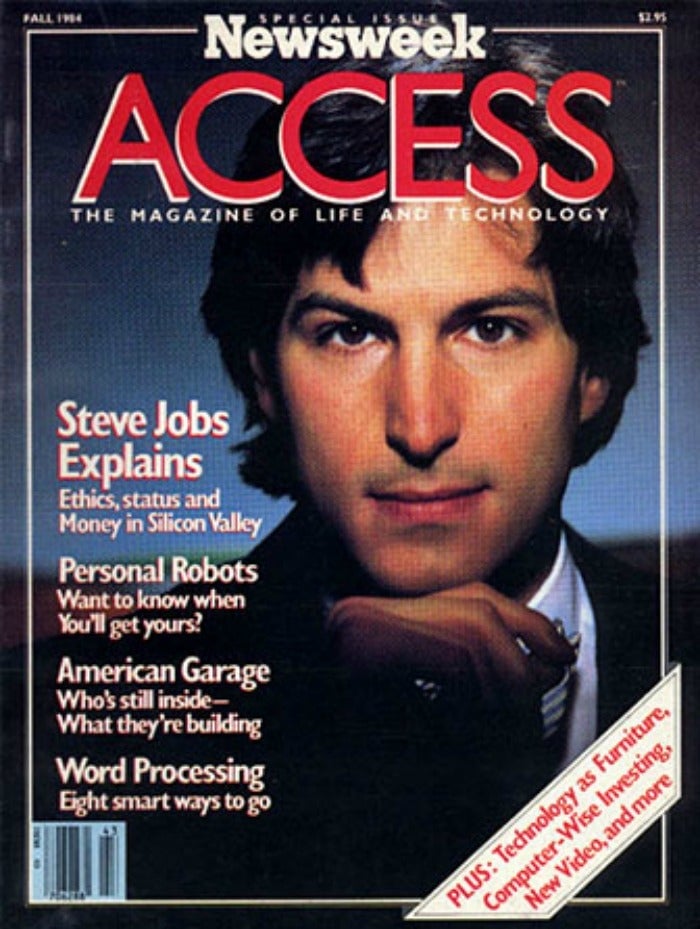

Newsweek Access: The Magazine of Life and Technology came out of that dinner as a one-shot that I hoped would turn into a quarterly. I put Steve on the cover in a tiny blue-and-white bow tie. Zito did the interview:

Zito: Is the computer business as ruthless as it appears to be?

Jobs: No, not at this point. To me, the situation is like a river. When the river is moving swiftly there isn’t a lot of moss and algae in it, but when it slows down it becomes stagnant; a lot of stuff grows in the river and it gets very murky. I view the cutthroat political nature of things very much like that. And right now our business is moving very swiftly. The water’s pretty clear and there’s not a lot of ruthlessness. There’s a lot of room for innovation.

Zito: Do you consider yourself the new astronaut, the new American hero?

Jobs: No, no, no. I’m just a guy who probably should have been a semi-talented poet on the Left Bank. I got sort of sidetracked here. The space guys, the astronauts, were techies to start with. John Glenn didn’t read Rimbaud, you know; but you talk to some of the people in the computer business now, and they’re very well grounded in the philosophical traditions of the last 100 years and the sociological traditions of the ’60s. There’s something going on [in Silicon Valley], there’s something that’s changing the world, and this is the epicenter.

Zito: Do you think it’s unfair that people out here in Silicon Valley are generally labeled nerds?

Jobs: Of course. I think it’s an antiquated notion. There were people in the ’60s who were like that and even in the early ’70s, but now they are not that way. Now they’re the people who would have been poets had they lived in the ’60s. And they’re looking at computers as their medium of expression rather than language, rather than being a mathematician and using mathematics, rather than, you know, writing social theories.

Zito: What do people do for fun out here? I’ve noticed that an awful lot of those who work for you either play music or are extremely interested in it.

Jobs: Oh yes. And most of them are also left-handed, whatever that means. Almost all of the really great technical people in computers that I’ve known are left-handed. Isn’t that odd?

Zito: Are you left-handed?

Jobs: I’m ambidextrous.

The reaction to Access was mixed. It was a handsome publication, but what was it about? Wasn’t it really kind of a cross between Popular Mechanics and Esquire? And how relevant was that? But Steve liked it—especially the cover shot, which made him look princely and brooding, even with that little bow tie.

*****

When Steve Jobs came to Time Inc. in February 2010, wearing New Balance sneakers, jeans, and a black mock turtleneck, I thought about his visit to Newsweek 26 years earlier in that little bow tie. He had arrived at Newsweek with one assistant to help him carry two of the Macintosh computers he was presenting then. There were at least eight people with him for his Time Inc. visit, and iPads were passed out to the top editors from Time, Fortune, People, and the other magazines, all of us seated at a long conference table. Coffee and tea were offered by waiters in white uniforms. Steve sat at the head of the table and spoke elliptically about innovation, quality journalism, and various business models while we played with his new machines.

I had never touched an iPad, although I had been working on an app to run on one for four months. The assignment had been to create the first tablet magazine, and Sports Illustrated had done that with jury-rigged touch-screen technology pieced together from Hewlett-Packard. Finally, to show that we were ready for the coming iPad, we had made a video simulation of what SI would be like on the tablet. It was primitive, with “zombie hands” to explain the touch navigation, and I had done the narration, but the video had gone viral—we loved saying that—with more than a million views and everyone in magazine publishing had seen it.

I turned on the new iPad and went to YouTube to see if the video would play. It did: “Hello, I’m Terry McDonell, the editor of Sports Illustrated, and here’s your new issue . . .”

I turned it off quickly, but the editor of Fortune, Andy Serwer, asked Jobs if he had seen the video. He had. What did he think? I’m sure Serwer was pushing for an acknowledgment that as a company, we were in the hunt—to use a popular catchphrase at the time. I’m also sure that most of the other editors in the room were tired of hearing about SI’s spurt of digital development and wouldn’t have minded Jobs knocking it down a little. I certainly didn’t know Steve Jobs, but I figured I still had to be on his radar and something very good could come out of SI’s iPad edition. I was hopeful.

“I think it’s stupid,” Steve said. “Really stupid.”

“Why?” I asked, jumping in, maybe too fast.

“It’s just a video,” Steve said. “It’s not real.”

“You gave us no choice,” I said. “And our app will work great on your appliance.” I still loved the word appliance.

“You made this?” he asked, I think realizing we had met before.

Before I could answer, Serwer asked Steve about getting access to Apple’s creative process. That was a good one if you knew their history—going back to a March 2008 Fortune piece titled “The Trouble with Steve Jobs,” which reported his eccentric cancer diet and raised questions about his involvement in the backdating of Apple stock options. Jobs had asked Serwer to kill it, and had then gone over his head to Time Inc. editor-in-chief John Huey, but Huey held the line and the piece had run.

I was expecting something far harsher than what Steve had said about SI’s iPad app, but he didn’t answer at first. I think Time managing editor Rick Stengel said something about how better access would make for more interesting journalism, and he’d like to be first in line.

“That will never happen,” Steve said finally, looking at Serwer, “after what you did.” He was talking about that Fortune story two years earlier, but instead of showing anger he was swallowing hard and his eyes were tearing.

“You kicked me when I was down,” Steve said. I think that’s when everyone in the room realized how sick he was.

Serwer said he was sorry, that he was just doing his job, that it wasn’t personal. But you could see it was very personal for Steve, who nodded, took a breath and moved on haltingly to his ideas about how publishers like Time Inc. had to be careful about “overpricing what you’re selling.”

Overpricing what you’re selling? Suddenly he was negotiating, even though none of the editors in the room had the authority to do anything beyond have an opinion. So . . . Apple would be taking its customary one-third and holding on to the credit card data. Apple might be willing to give us some of that data back—“customers’ names and stuff ”—but not the credit card info, which he said was protected by Apple’s privacy policy. We were fucked.

The meeting ended with the iPads being collected and Steve pushing away from the table while saying, “I’m interested in magazines.”

I hung back as the other editors filed past to say good-bye. When they were gone, I reminded Steve where we had met and about Newsweek Access. He said he remembered, and that Tom Zito had sent him a photo from the SI 2007 Swimsuit Issue of Marisa Miller on her back on a white beach, naked except for an iPod. Was I responsible for that? I was. I had sent it to Zito to send to him, and I knew what he had e-mailed back to Zito—who had forwarded the e-mail to me.

“Really,” Steve said, and waited.

“ ‘Does she want a job at Apple?’ ” I said, quoting his e-mail.

“A joke,” Steve said.

“I know.”

“Like this meeting,” he said.

An hour after Steve left, his top developer-relations guy called to say that “Steve and the team” really thought there was a lot of cool stuff in the SI demo, and they’d love to work with us to create a version of SI for the iPad release, which was then only 60 days away.

SI was ready to go; but the first Time Inc. digital magazine—the first digital magazine, period—to run on the iPad was to be Time. Steve “wasn’t into sports,” as it was explained to me a week later, and Time had always been one of his favorite magazines. Time had agreed to put him on the cover after he made some calls himself—and it became clear that Apple’s approval was required not only to run an application on the iPad but also just to get into the Apple App Store. The leverage was embarrassingly obvious. Stengel thanked SI in his “Editor’s Letter” when the issue launched.

Excerpted from the book THE ACCIDENTAL LIFE by Terry McDonell, copyright 2016 by Terry McDonell. Published by arrangement with Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.