How a solar storm almost turned the Cold War hot

In 1967, Cold War tensions were running high. Five years earlier, the Cuban Missile Crisis had kept the entire United States on edge for 13 days straight, and in 1965 troops were sent to Vietnam for the first time. Since 1957, one third of the US Air Force’s bomber fleet was on alert (pdf) at any given time, ready to fire up their engines and take off in 15 minutes or less. It was in this tense, paranoid atmosphere that one of the largest solar storms of the 20th century erupted and nearly triggered an unprovoked attack on Soviet Russia.

In 1967, Cold War tensions were running high. Five years earlier, the Cuban Missile Crisis had kept the entire United States on edge for 13 days straight, and in 1965 troops were sent to Vietnam for the first time. Since 1957, one third of the US Air Force’s bomber fleet was on alert (pdf) at any given time, ready to fire up their engines and take off in 15 minutes or less. It was in this tense, paranoid atmosphere that one of the largest solar storms of the 20th century erupted and nearly triggered an unprovoked attack on Soviet Russia.

A new paper, published Tuesday (Aug. 9) in the journal Space Weather, details the effects of that solar storm and the confusion it caused among Air Force commanders.

When the Soviet Union launched Sputnik in 1957, kicking off the space race, the US Air Force decided to expand its Air Weather Service. Instead of just forecasting terrestrial weather for the military, they also started attempting to predict solar and geophysical events that could affect space missions, like solar flares and disturbances in the Earth’s magnetic field caused by the sun. Soon, a system was developed that allowed the weather service to report its findings and concerns to commanders at the North American Air Defense, more commonly known as NORAD, which coordinated defense efforts between the US and Canada.

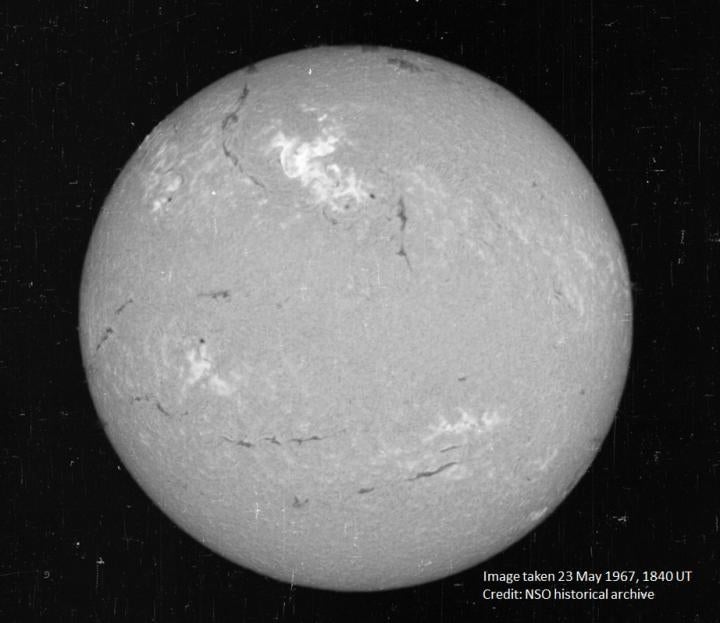

This system was critically important on May 23, 1967. On the surface of the sun, a storm erupted over a sun spot, producing a burst of white light on the sun’s surface that could be seen with the naked eye all the way down on Earth. X-rays and extreme ultraviolet light hit Earth’s ionosphere, an upper layer of the atmosphere, affecting how radio waves were transmitted. Bursts of radio waves were emitted and the aurora borealis, an electric storm in the upper atmosphere caused by solar winds, was seen as far south as New Mexico.

All those radio waves emitted by the solar storm reached Earth at midday in North America. Everywhere that sunlight touched, radio waves bombarded the planet, including key radar sensors in Alaska, Greenland, and England that were part of the Ballistic Missile Early Warning System (pdf), a network strung together to act as a warning system, alerting of incoming missiles from Russia before they reached their targets.

To US military commanders, the radar readings looked suspiciously like someone was jamming their signals with strategic radio interference. And if the Russians were behind the radio interference, it would be an act of war, worthy of calling the Air Force fleet into action. With radio communication limited, calling back aircraft would have been nearly impossible.

Fortunately, reason and caution prevailed. The space weather forecasters were able to convince higher-ups that the sun was the source of the interference, preventing a maneuver Russia surely would have seen as a provocation.

This wasn’t the first time this had happened, actually. Back in the early days of radar during World War II, British radar operators noticed (paywall) strong radio interference all over England. But the culprit turned out to be solar radiation in that case, too: eventually, they figured out that the interference only happened during the day and always came from the direction of the sun.