IBM is gearing up to become the world’s largest and most sophisticated design company

In this series, Perfect Company, we are examining pockets of excellence in the corporate world. No single company is perfect, but together they show what the corporate ideal could look like.

In this series, Perfect Company, we are examining pockets of excellence in the corporate world. No single company is perfect, but together they show what the corporate ideal could look like.

The platonic ideal

“Design is not style. It’s not about giving shape to the shell and not giving a damn about the guts. Good design is a renaissance attitude that combines technology, cognitive science, human need, and beauty to produce something that the world didn’t know it was missing.”—Paola Antonelli, senior curator of the Museum of Modern Art

The practice

In 2012, IBM, the 105-year old information technology company, set out a bold vision: To flood its ranks with hundreds of designers and train its entire workforce—some 377,000 employees worldwide—to think, work, feel like designers. Like it did 60 years ago, IBM is looking to bolster its bottom line through a design-minded culture, but this time at a more ambitious scale involving the entire company.

The ethos of IBM’s design renaissance is radically different from its storied Corporate Design program that it maintained for 20 years. In 1956, IBM founder and president Thomas J. Watson looked to the “imaginative use of design” to boost sales with the now famous call-to-arms “good design is good business.” But today, instead of hiring big name geniuses like Eliot Noyes, Eero Saarinen, Paul Rand, and Charles and Ray Eames as it famously did in the 1960s, IBM is aggressively hiring new graduates and mid-career designers with an aptitude for collaboration. “The challenges are just too great for one designer,” explains Phil Gilbert, general manager of design for IBM software, of their new team-based design philosophy.

But of all professions working at IBM—scientists, engineers, business professionals—why make designers the ideal?

“Designers bring this intuitive sense for what it [the assignment] means. They understand the power of delivering a great experience and how to treat a user as if they were guests in their own home,” says Gilbert, who’s also the company’s designated chief design evangelist.

Gilbert explains that the design program allows the $143 billion company to be more strategic and shift away from the engineering-driven “features-first” ethos towards a more “user first” mentality. “It allows us to solve real problems for real people instead of building a few features here and there,” he says.

In a recent project, an airline approached IBM to improve its kiosks to speed up passenger gate check-ins. While the engineers started by improving the kiosk’s software, designers went straight to gate agents to ask why the check-in kiosks weren’t used more effectively. Designers found out that female gate agents struggled to keep kiosks charged because their constricting uniforms prevented them from reaching electrical plugs behind the machines. By finding the root of the problem, IBM delivered a mobile app that significantly eased the boarding process and reduced airline costs.

Gilbert explains that training staff to think like a designer helps them tune in to “emotional connections” and develop a keen interest in clients’ struggles, pressures, and insecurities. “That doesn’t come naturally to other disciplines, but it comes naturally to designers—it’s the way designers approach a problem.” Design, Gilbert explains, has become a kind of overlay to IBM’s business and engineering practices. “If you don’t have all three [departments] you won’t have a good outcome reliably, at least not at scale.”

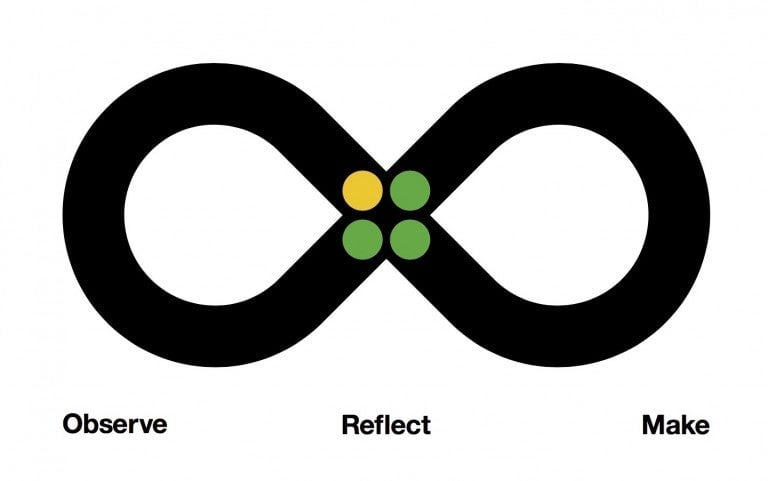

In IBM’s design bootcamps, empathy—the ability to understand another’s feelings—has been a mantra for groups trying to better connect with colleagues and clients. They learn about rapid prototyping, team dynamics, problem solving, and how to tap into their customers’ and colleagues’ feelings and concerns to come up with better tech solutions.

“Design is everyone’s job. Not everyone is a designer, but everybody has to have the user as their north star,” writes Gilbert in the company blog. By the end of 2016, 100,000 IBM staffers will have gone through some sort of design training.

In three years, IBM has also more than tripled its design staff, with 1,300 formally trained designers working in 31 studios from Boston to Böblingen, Germany. It acquired four digital and branding agencies, and built the largest studio network in the world. IBM is quickly assembling a kind of Noah’s Ark of designers working on product, graphics, interface, branding, and even an in-house typographer.

Among this new tribe of creative people at IBM are design researchers—formally trained ethnographers with MFA degrees to probe how their solutions are working in the real world. Working in project teams, they conduct interviews and collect data to better understand the nuances of an assignment. Gilbert says having researchers with ”open minds and open hearts” allows developers to validate their ideas and better anticipate the needs of their clients. ”The design researcher has been the most disruptive of the design disciplines we’ve brought in—and by far the most transformative,” he says.

With $100 million earmarked for the initiative, IBM is aggressively pushing the design enculturation campaign in all its internal systems, from hiring, to training, employee review processes, to the layout of office spaces and even the way office supplies are ordered. “When we started the program it wasn’t easy to get Post-It’s,” says Gilbert, of the requisite office supply and symbol of design thinking powwows. ”Today, they’re in our system—just push a button and you can get Post-Its. That’s a profound change.”

The takeaways

To stretch its investment, IBM is intentionally filling two-thirds of its design ranks with new graduates. Gilbert says this strategy helps invigorate established processes. “We’re building this [design] program for the long term and we wanted people with very fresh perspectives on the world, on the profession, on what a design culture should be,” he explains.

The focus on design thinking has instilled a more collaborative, group meeting-based culture that may not be immediately embraced by all employees. “It’s not just radical collaboration but radical transparency,” explains Gilbert. “It’s a sharing of intentions, motivations, and information.” He says that IBM had to revamp its internal systems to introduce collaboration and brainstorming platforms like GitHub, Slack, and MURAL.

Introducing design researchers—specialists with science and humanities backgrounds—has brought the most profound change to the company’s operations. Gilbert explains that some IBM engineering and business teams are startled to encounter designers who speak in terms of sociological data rather than pretty prototypes. ”Design used to be form and color, but understanding a user … in that sense it could appear to be threatening,” he says. “It’s hard and messy, but you get much richer outcomes.”

IBM’s aggressive and zealous design-minded approach can help promote a more nuanced definition of design’s purview. Just by the scale of its presence in 170 countries, IBM can re-contextualize roles and careers for the design profession around the world. Expanding design’s influence beyond finessing shapes, beautifying screen interfaces, and tidying up presentations, IBM’s trained employees can demonstrate how design thinking can improve and humanize solutions for the world’s most urgent matters, from detecting cancer and fighting the Zika virus to providing drone operators with real-time weather data.