Chinese online shoppers spent $190 billion in 2012. Here’s a look at how—and what—they bought

The headline number from the Chinese government report on e-commerce is the sales: 1.26 trillion yuan ($190 billion). However, the annual report (pdf, in Chinese), which is researched and published by the absurdly named Chinese Internet Network Information Center—and claims the not-quite-right acronym of CNNIC—is rich in detail about how e-commerce habits are developing in China—and who’s benefiting from them. Here are some underlying trends worth noting:

The headline number from the Chinese government report on e-commerce is the sales: 1.26 trillion yuan ($190 billion). However, the annual report (pdf, in Chinese), which is researched and published by the absurdly named Chinese Internet Network Information Center—and claims the not-quite-right acronym of CNNIC—is rich in detail about how e-commerce habits are developing in China—and who’s benefiting from them. Here are some underlying trends worth noting:

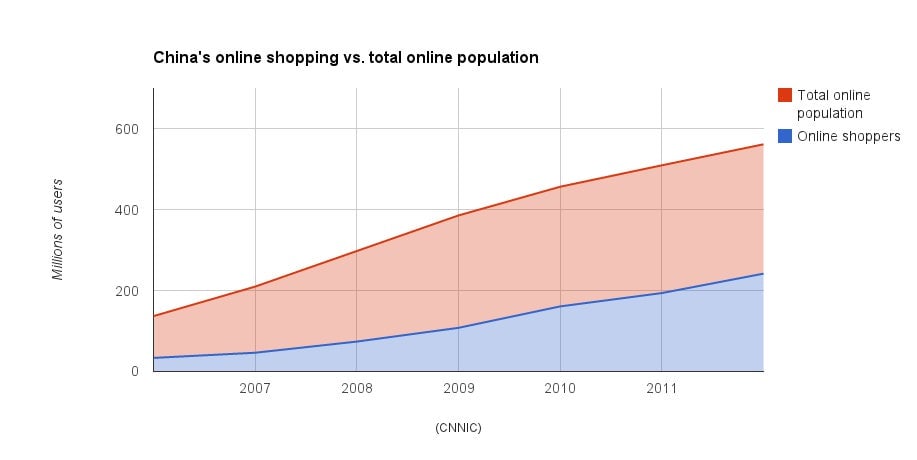

In China last year, 242 million people—that’s more than the population of Indonesia—bought goods online. That’s up from 194 million in 2011 (pdf, Chinese)—when it was the equivalent of Brazil—and, in 2010, the 161 million (pdf, Chinese) that put it somewhere between Nigeria and Bangladesh. And though the rate of online shopping take-up has picked up a little in the last year, there’s clearly still a lot of room to grow (see above chart).

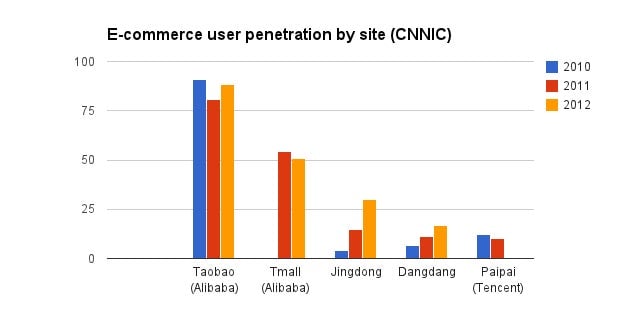

Alibaba continues to dominate Chinese e-commerce. Some 212 million people shopped via Taobao, its consumer-to-consumer site (an analog of eBay), in 2012, while 155 million used Tmall, the business-to-consumer site (more like Amazon). However, the user penetration of both sites—the percentage of online shoppers who have used them in the past year—is coming down a bit. And Tmall’s competitors—notably Jingdong and Dangdang—were closer on its heels in 2012. Here’s a look at that trend over the last three years:

Mobile shopping is gaining ground, with 13.2% of online shoppers using their phones to buy stuff last year. That’s up from 12.1% of them in 2011. Of those, more than 53% used an app for a given online store, as opposed to its website, compared with 42% in 2011. (The significance of this figure is that people who download the app are more likely to be regular shoppers.)

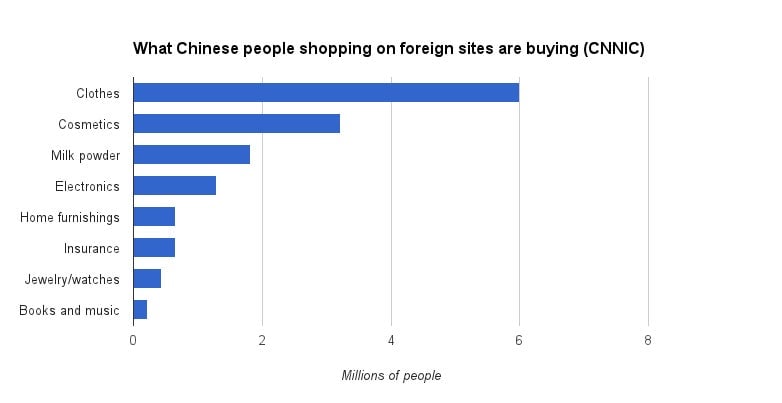

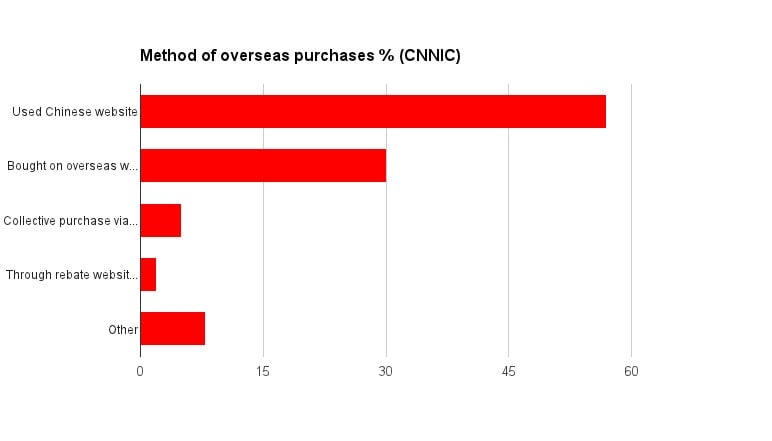

Nearly 12 million Chinese bought overseas goods online in the second half of 2012. This is the first year CNNIC tracked this, so one can’t assess how new the trend is. Still, the figure is notable. For one thing, shopping on foreign sites is a headache, as it usually requires overseas credit cards that are not widely available in China. It’s not surprising, therefore, that most people who bought overseas goods did so via domestic sites:

In the last six months of 2012, Chinese shoppers purchasing goods overseas made an average of four purchases totalling 1,698 yuan ($275). Remarkably, nearly 40% of those shopping overseas did so because it was cheaper than buying domestically, suggesting the extreme markup on foreign goods sold in China won’t be sustainable forever. Around 34% said it was because the brand they wanted wasn’t available in China, and another 30% cited product quality guarantees. Clothes and cosmetics were both big sellers. Also remarkable is that that nearly 2 million enterprising Chinese online shoppers skirted a limit on bringing milk powder from Hong Kong to the mainland (where it is in high demand) by sourcing it online. They’re probably a big portion of the “quality guarantee” contingent.