A ghost town in Italy is about to come back to life for a hide-and-seek “world championship”

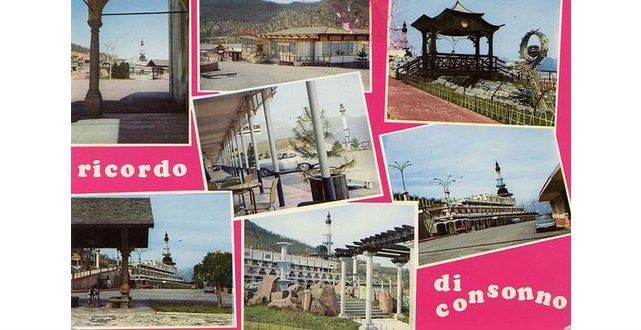

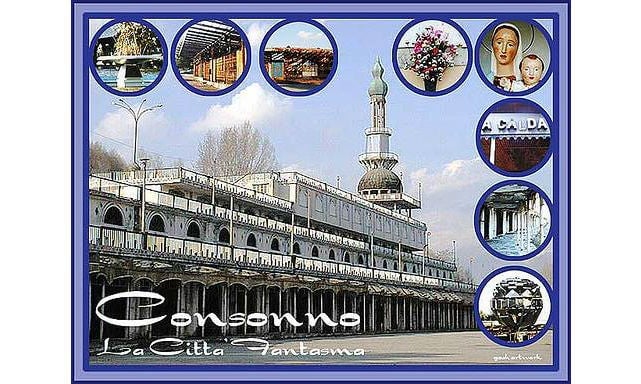

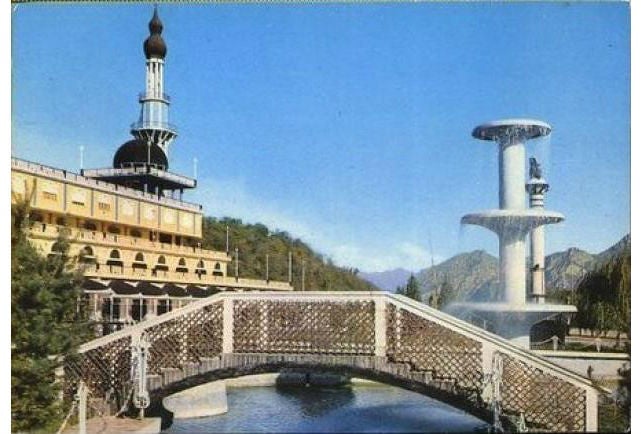

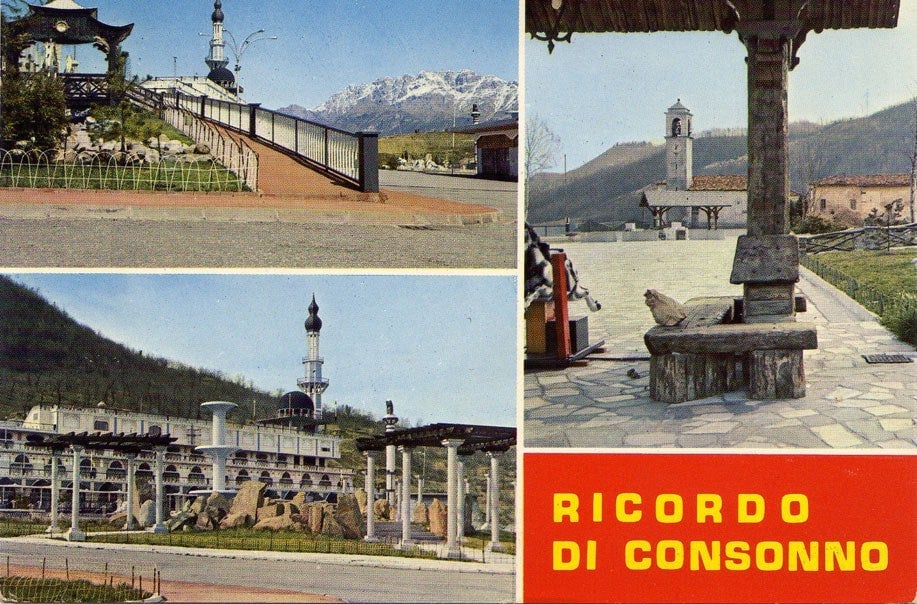

The hilly village of Consonno, set in the foothills of the Alps in Lombardy, northern Italy, was once known as Milan’s “Land of Toys.” It was built in 1968 by Count Mario Bagno, a real estate developer who wanted to create an Italian Las Vegas, after he had convinced the locals to let him demolish the ancient rural town with false promises of development and wealth. For eight years, with its Grand Hotel Plaza, a night club, several buildings of eclectic design (a pagoda, a minaret), a zoo, and even a small sightseeing train, the town was a party destination.

The hilly village of Consonno, set in the foothills of the Alps in Lombardy, northern Italy, was once known as Milan’s “Land of Toys.” It was built in 1968 by Count Mario Bagno, a real estate developer who wanted to create an Italian Las Vegas, after he had convinced the locals to let him demolish the ancient rural town with false promises of development and wealth. For eight years, with its Grand Hotel Plaza, a night club, several buildings of eclectic design (a pagoda, a minaret), a zoo, and even a small sightseeing train, the town was a party destination.

In 1976, a landslide destroyed the road that connected Consonno to the nearest town, blocking access to the village. It was the end. The village decline was rapid and irreversible, and despite Bagno’s attempt to revive his project, Consonno became a ghost town. With its combination of dilapidated buildings and beautiful natural landscape, it is occasionally used as a setting for music videos and movies.

But come Sept. 3 and 4, it will revert to its ludic purpose and host the sixth annual Nascondino World Championship, a hide-and-seek competition drawing hundreds of participants, all of them from Italy.

Giorgio Moratti, a member of the organizing team, says the championship was first held in 2010 in Bergamo, Italy, as an initiative of CTRL Magazine, a local publication, but the scenery of Consonno as well as the abundance of hiding spots in the town’s many abandoned buildings won over the group. “Looking at those fields,” Moratti told Quartz, “we immediately imagined they’d be perfect to play hide and seek! And that was the beginning.”

The first year, 15 teams participated. The following year, 25. Then, the competition’s name, initially just a “Nascondino (hide and seek) championship” was updated to ”world championship,” to make it seem, well, more worldly. “Let’s say it’s more of an ambition than the reality,” said Moratti, “but every year we work to make it larger.”

Participants, who pay and entry fee of €125 per team, are between 18 and 60 years old, and the teams are coed. This year, 64 teams of five members each will be hiding in Consonno. The rules are simple, but strict, and enforced by two referees and a game coordinator. The teams are divided in four groups, and one person per group hides while a “neutral searching team” counts 60 seconds. Participants then have 10 minutes to jump out of their hiding spot and hit a target in the middle of the playing field, without being found or caught by the searching team. The competition continues for two full days, until a winner is declared.

In 2014, the winning team was part of a rugby team from Lumezzane, near Brescia. Michele Zeffino, one of the participants, told Quartz they participated “because we wanted the title of world champions of hide and seek.”

“It was pretty competitive,” Zeffino said, “each team had their tactics, and they were all effective.” He said his team had to improvise, but has learnt some tricks it will employ in the coming contest. He is determined to keep such tricks secret (“obviously we will never disclose them,” he said), though he noted that “the hardest part is to decide when to come out from hiding.”

Hide-and-seek is popular all over the world, and its popularity has driven hopes that it would become an Olympic sport. Yasuo Hazaki, a graduate of Nippon Sport Science University, and professor of media studies at Josai University in Sakado, Japan, had set up a campaign in 2013 to promote it for the 2020 Olympics in Tokyo. Moratti said the championship organizers, after reading about Hazaki’s interest in the game, contacted him, and were able to discuss hide-and-seek with him.

The game Hazaki was promoting was a slightly different traditional Japanese game, more similar to a game of tag, but after hearing more about hide-and-seek and the tournament, he became a fan. “He kept asking questions about our competition, even technical things, and said this game is even more appropriate to be a candidate to the Olympics,” Moratti says, although the Olympic campaign hasn’t been successful.

Every year, Moratti says, the Italian press gets more excited about the championship, and the tournament has drawn some international interest. He hopes some day “to officially become a world championship” and have non-Italian teams compete.