25 years ago, a failed coup in Moscow killed a superpower. Now it’s back

Who is the biggest wild card in the extraordinary US presidential election? Is it the renegade Republican nominee, Donald Trump? His bombastic new campaign chief?

Who is the biggest wild card in the extraordinary US presidential election? Is it the renegade Republican nominee, Donald Trump? His bombastic new campaign chief?

Or is it, as some believe, Russian president Vladimir Putin?

In recent weeks, Putin has reinforced his image in the West as a menacing force, with renewed military advances near home and in the Middle East, and a plot to corrupt the Olympics. But it is fresh allegations of hacking the American security edifice, after similar reports of intrusions into Democratic Party computers, that have ignited worry that Putin may pose a threat to the US election.

All in all, it is a clearer picture than ever that Russia is back, marking the end of a long, painful chapter in Russian history that began 25 years ago today.

On Aug. 19, 1991, a group of Soviet generals launched a coup against leader Mikhail Gorbachev. Arguably more than any other single event, the rapid disintegration of their effort marked the final death blow to Moscow’s capacity and will to muster hard power. Four months later, the Soviet Union collapsed.

If Putin is in fact interfering with the US election, he is merely reviving the Russian side of a great power rivalry that, before the coup, featured countless episodes of similarly high-stakes, cloak-and-dagger hijinks.

“We are now simply seeing what it looks like when a major power acts in furtherance of what it understands to be its interests, irrespective of US interests,” says Matthew Rojansky, director of the Kennan Institute in Washington, DC.

Back to the future

During the Cold War, American and Soviet intelligence agencies went after each other robustly at home and abroad. The Soviets managed to steal the US blueprint for the nuclear bomb. Robert Hanssen, an FBI agent, spied for the Soviets for 22 years before being caught in what was called “possibly the worst intelligence disaster in US history.”

For decades, the US and the Soviet Union conducted proxy wars around the world, among them in Angola, El Salvador, Korea and Vietnam. The US dominated the strategic Middle East, especially after Egypt switched superpower patrons in 1972, but the Soviets were in the region, too, with a base in Syria.

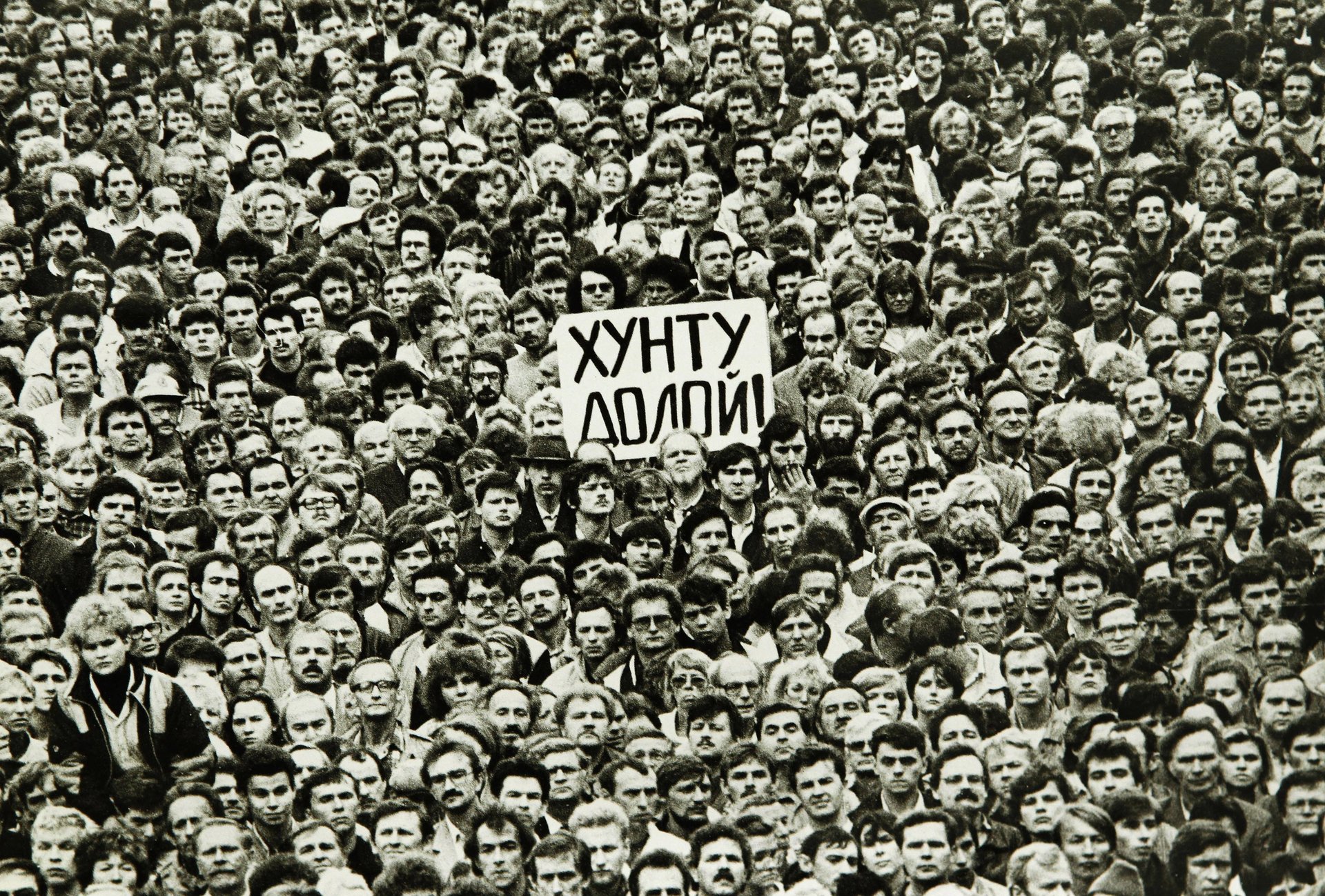

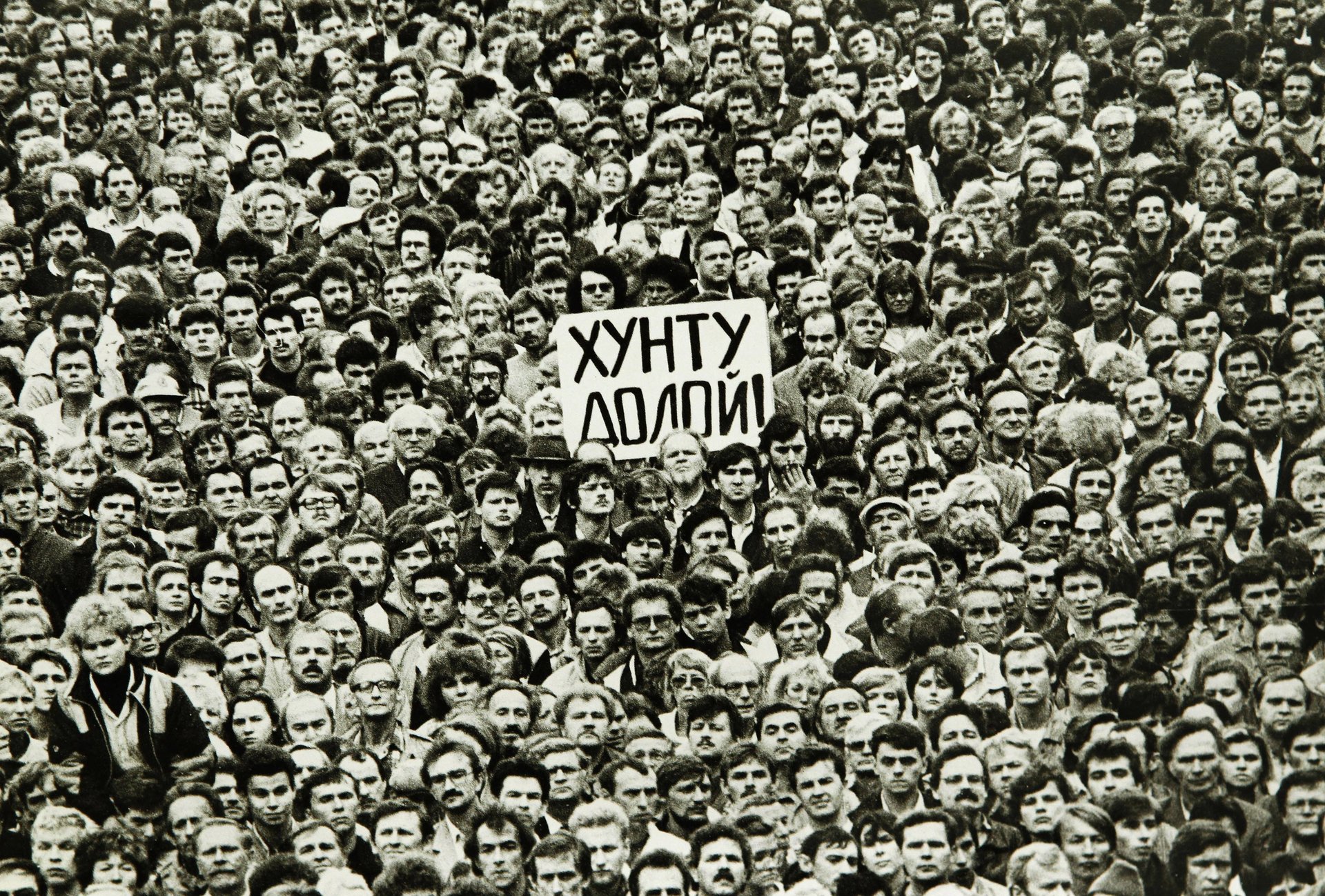

The end was already in sight before the August 1991 putsch, but the episode added finality to the Soviet disintegration. It is only vaguely remembered now, but at the time it was the biggest news in the world, a shocking moment when the small group of generals detained Gorbachev, sent tanks into Moscow’s streets, and said they were putting a stop to perestroika, as Gorbachev called his reformist policy. When the Soviet vanguard did not fall into step with the putschists, and Muscovites bravely went into the streets to resist (see photo above, in St. Petersburg), the clock visibly and undeniably started counting down on the last days of the Soviet Union.

Putin’s recent series of foreign adventures is reminiscent of the prior era. Over the past few days, Russia jets have taken off from Iranian soil on bombing runs into Syria, the first time in seven decades that Tehran has permitted a foreign military to use its territory. There are also reports that Russia has amassed tens of thousands of troops and built new military installations along the Ukrainian border, suggesting the potential for a resurgence of fighting on the margins of the European Union.

But the thing that has made Putin seem a particular threat in the US has been Russia’s cyber-hacking network, which is allegedly behind an offer to sell America’s most powerful tools of espionage, after it already broke into Democratic Party email servers. Moscow’s alleged penetration of the National Security Agency—which boasts that it’s the best hacking organization in the world—has escalated American worry that not only could Russian cyber intrusion upset the 2016 US elections, but the US espionage apparatus itself.

We are witnessing the establishment of a “new normal,” says Rojansky. “This is what it looks like when we have major power rivals who don’t share our geopolitical agenda or our worldview.”