An Indian acid attack survivor is taking her inspiring story to New York Fashion Week

Reshma Qureshi may be scarred for life but she is not going to brood over it.

Reshma Qureshi may be scarred for life but she is not going to brood over it.

In fact, she will soon be travelling abroad for the first time ever, flying to New York City to walk the runway during New York Fashion Week in September.

That’s a big deal for the 19-year-old acid-attack survivor—she has no sight in one eye and her face is almost completely disfigured, covered in scar tissue.

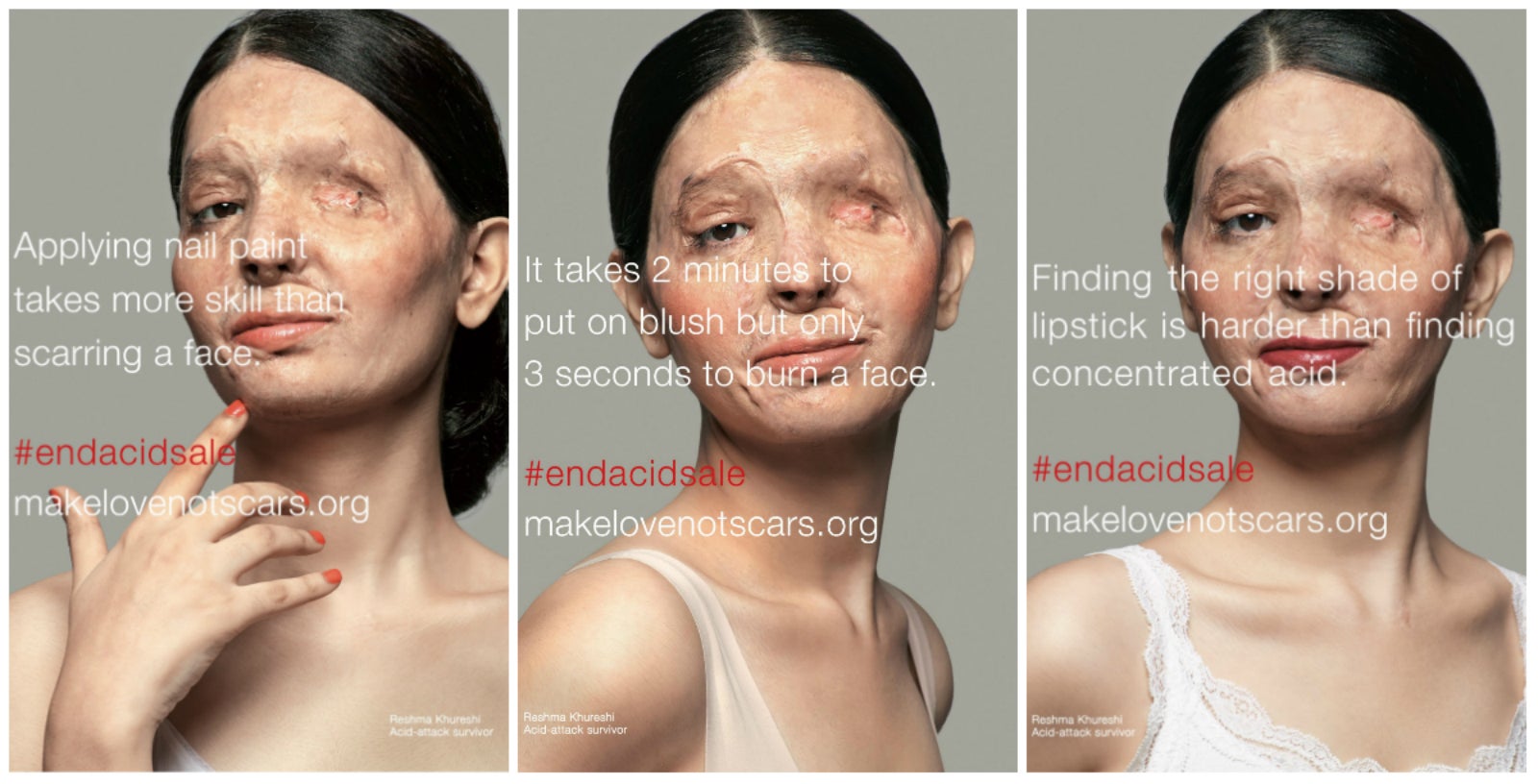

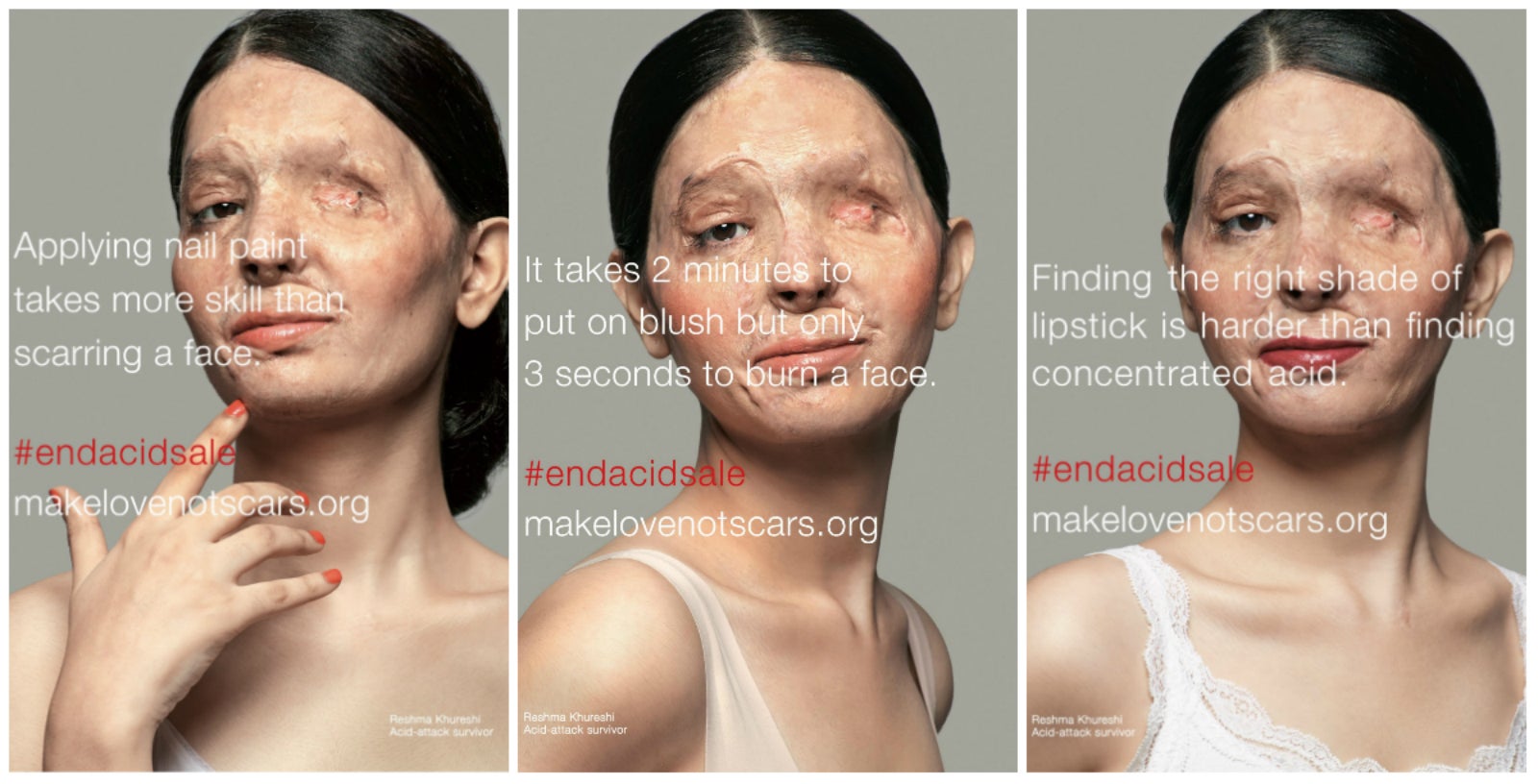

Qureshi is the face of the #EndAcidSale movement of New Delhi-based NGO Make Love Not Scars. She is best-known for her videos that begin with providing makeup tips and go on to shock viewers with information on how acids, sold freely across the country, ruin lives.

A corroded life

In May 2014, Qureshi and her sister Gulshan were visiting Allahabad in the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh when her life was torn apart.

On her way to appear for the Class 10 examination, the two were accosted by Gulshan’s estranged husband and two accomplices. As Qureshi fought to help her sister, the attackers turned on her, pouring acid on her face and leaving her in excruciating pain, disfigured for life.

“We asked people for help but no one helped us,” Qureshi remembers. The hospital she was first taken to gave her the bare minimum of treatment. It wasn’t until she returned to Mumbai that she was able to begin the long process of treatment and surgeries.

In a society where a woman’s worth is still tied to her appearance, the disfigurement, physical pain, and psychological trauma that acid attacks cause give women like Qureshi a lifetime of difficulties.

The mission of Make Love Not Scars is to use videos and vlogs to give them a platform to push back against beauty norms and help reclaim their lives and stories. For, Qureshi is only one among hundreds of Indian women to suffer this horrific crime every year.

In 2014, 309 cases of acid attacks were reported in India and though the data does not break down the number by gender, women are often the worst-affected.

A year earlier, alarmed by the increasing numbers, India’s supreme court ordered state governments to regulate the over-the-counter sale of acids. It stipulated that such sale would require licences and retail stockists would have to keep detailed records of their customers.

However, the open sale of acids continues even now, often for as little as Rs25 for a small bottle.

The new regulations also promised financial aid of at least Rs3 lakh ($4,500) to survivors. Thanks to this assistance, the data for 2014 jumped due to improved reporting of acid-attack cases. But this is of little help as many survivors are yet to receive the compensation.

Qureshi, for instance, had to rely on the NGO to pick up the pieces.

Clearly, much more needs to be done to sensitise the authorities and society to its horrors.

The first step is empowering the victims, making sure the world knows them for more than just their horrific experiences.

Reshma Qureshi, headed for New York, is just the person to call.