Researchers have uncovered an ancient Mexican text that had been hidden for 500 years

Researchers have just revealed an invaluable manuscript that Mesoamerican scribes covered up some 500 years ago—and it’s right under another rare document depicting ancient life in Mexico.

Researchers have just revealed an invaluable manuscript that Mesoamerican scribes covered up some 500 years ago—and it’s right under another rare document depicting ancient life in Mexico.

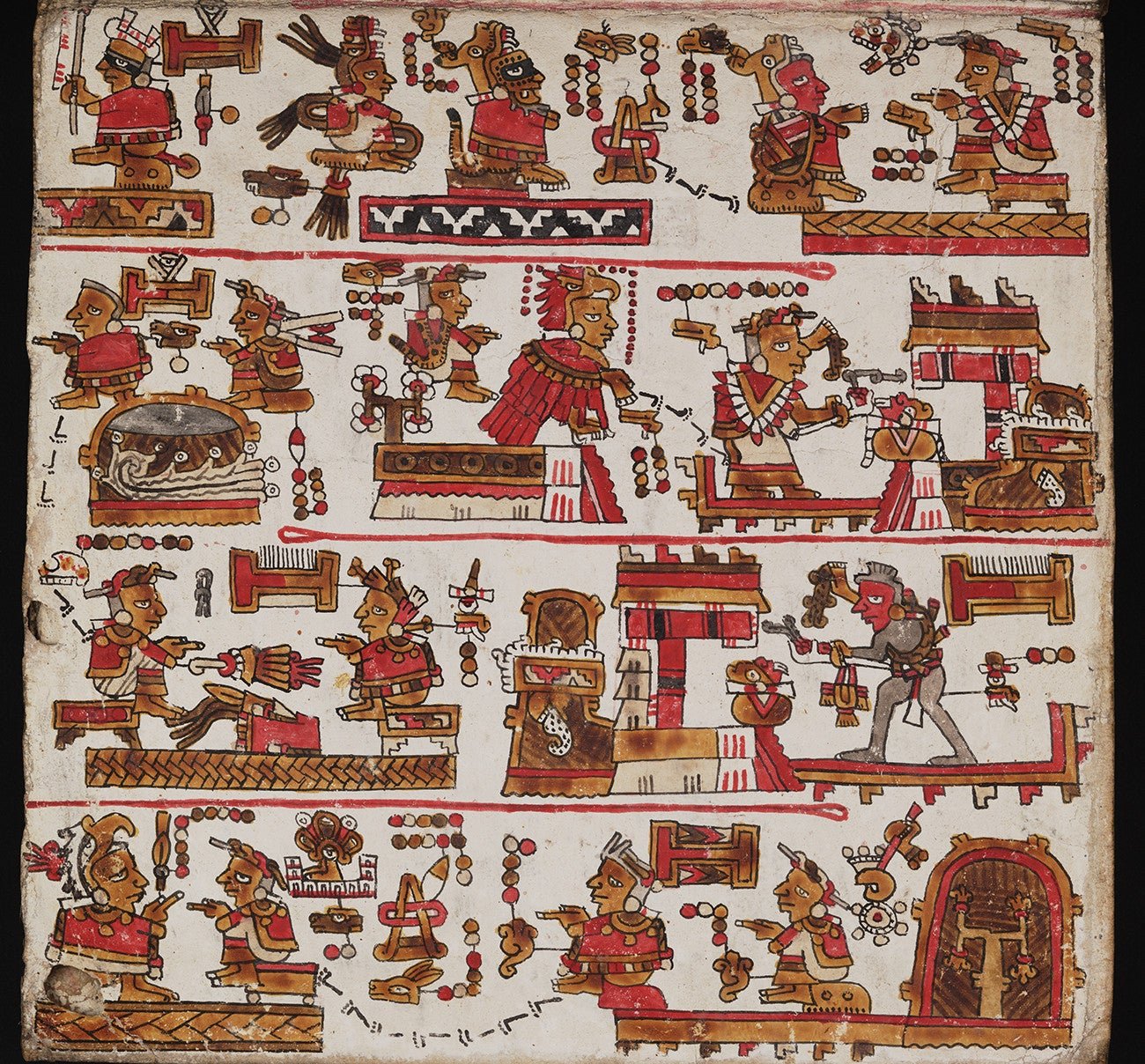

The newly discovered text appears to contain new knowledge about the Mixtecs, one of the major Mesoamerican cultures, according to a study in the Journal of Archeological Sciences: Reports, released earlier this month. It’s a rare find, considering there are fewer than 20 codices known to have survived the 16th century Spanish conquest and colonization of what is now Mexico and Central America. Of those, five are from the Mixtec area, today’s Oaxaca state.

The Mixtec manuscript was hidden on the backside of the 1560 codex Añute, a 20-page book drawn on a leather strip that folds like a concertina. (The codex Añute is also known as codex Selden, after a previous owner.)

For decades, archeologists suspected other pictograms were there, concealed under the layer of gesso that Mixtecs used as a writing surface. But they didn’t know how to uncover the images without damaging the artifact, so they left them hidden. In the 1950s, a team actually scraped the back surface of the codex, but turned up very little.

Now researchers from Leiden and Delft Universities in the Netherlands and Oxford’s Bodleian Libraries, where the codex is stored, have reconstructed whole pages of the document without making a single scratch.

They used hyperspectral imaging, a technique once used by scientists to study the color of stars. When applied to old and frayed documents, this type of scanning collects the reflection of light pixel by pixel in 900 different wavelengths in the electromagnetic spectrum, way more than the naked eye can perceive.

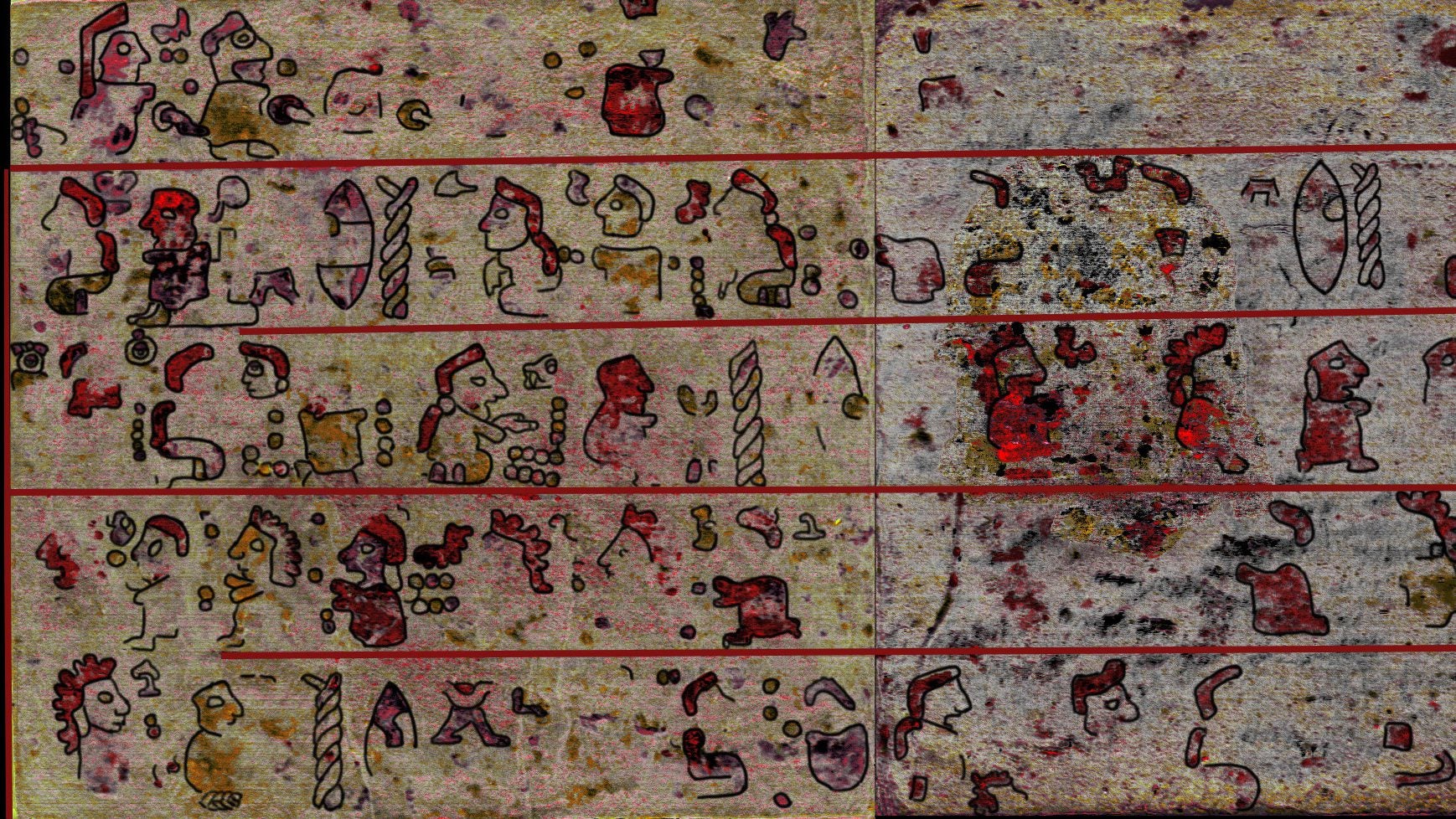

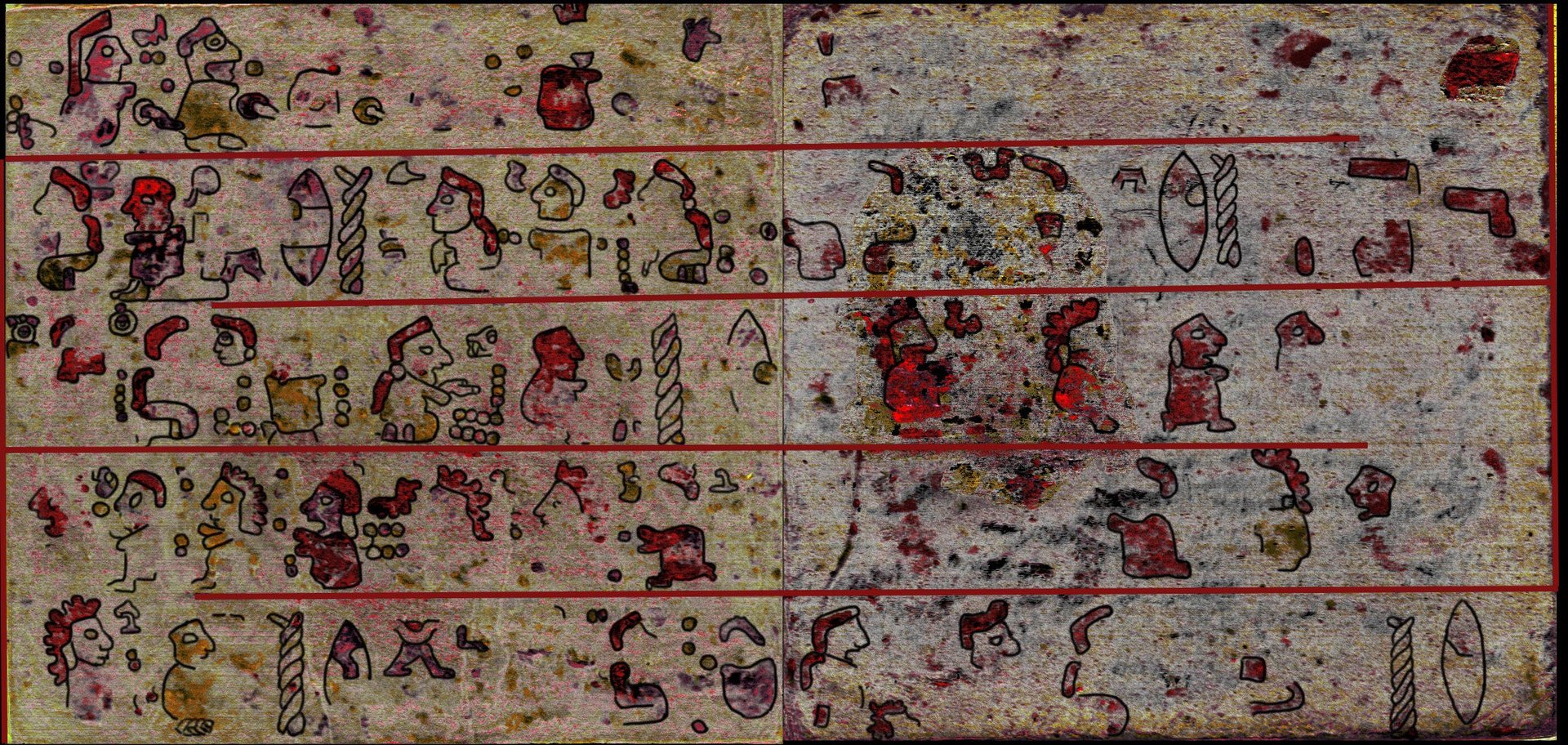

After processing the scanned data with special software, the research team was able to turn this:

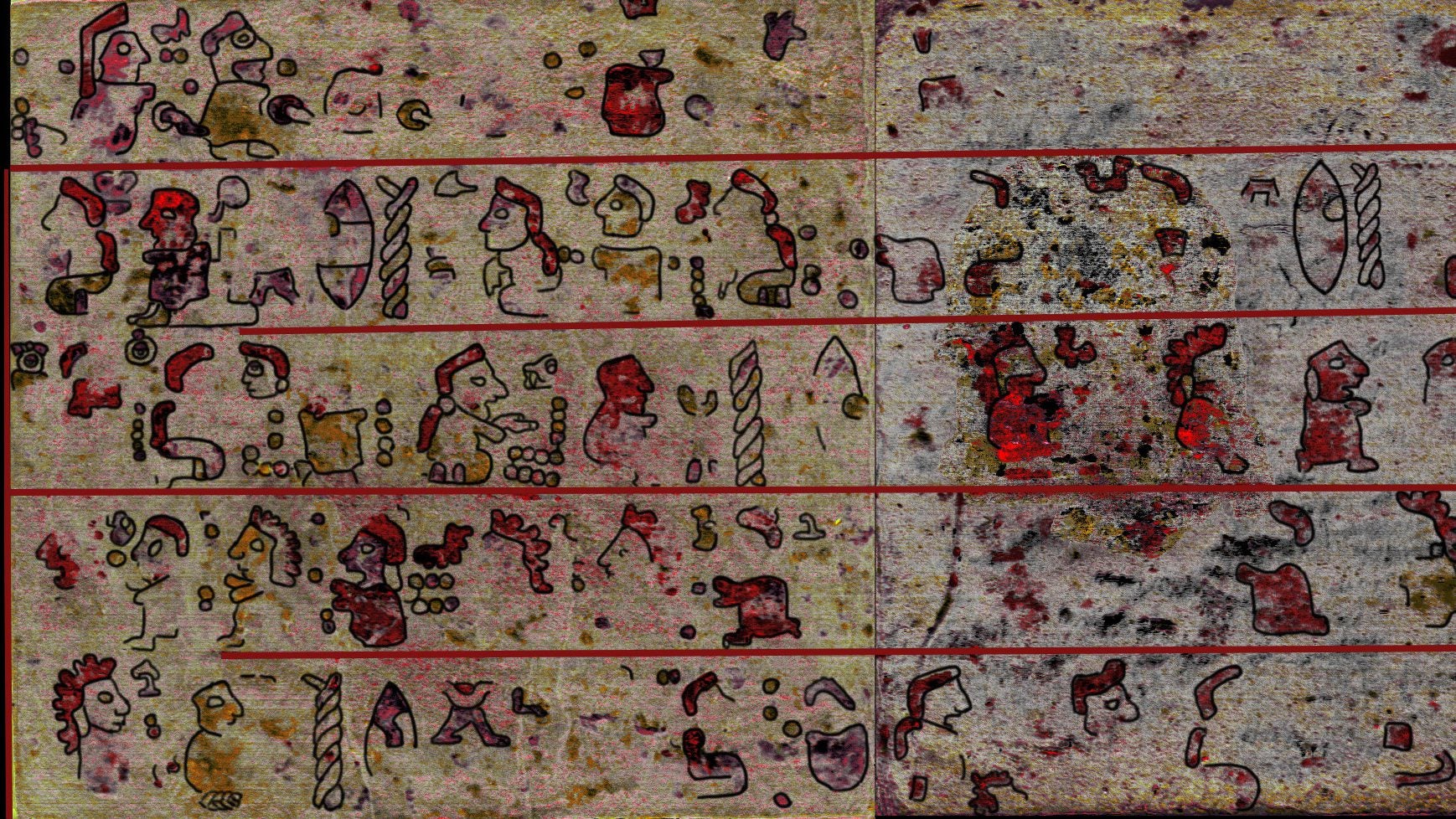

Into this:

Mixtec codices track the genealogy and deeds of historical figures and can be linked to existing archeological sites. The recovered images appear to contain a bounty of new information, including the names of several of the people depicted in them.

One of them, represented repeatedly as a twisted cord and a flint knife, was likely a prominent individual, say researchers. Two others, in the top left corner, were brothers, attached by red umbilical cords in the codex depiction. There are also female characters, shown sitting on their knees.

It will take years of research to figure out what the scene represents, but it is known that women played an important role in pre-colonial Mixtec society, taking part in government along with men, says Ludo Snijders, one of the paper’s authors. What is certain is that the newly discovered document is different in style and content from all the other Mixtec codices, and thus promises to shed new light on that culture.

“This information allows us to really get down to the actions of individuals, which can be very difficult to recover archaeologically,” says Snijders.