Designers have an 8-letter word for the despised hipster aesthetic colonizing the planet

Call it the Brooklyn look.

Call it the Brooklyn look.

The “Brooklyn of (insert any city)” has become the global nomad’s shorthand for any town’s trendiest, most visually eclectic, and often most clearly gentrifying area. Such enclaves include the suburb of Pantin of Paris, Shimokitazawa neighborhood in Tokyo, Florentin in Tel Aviv and Shoreditch in East London. What the Brooklyns of the world have in common is an aesthetic: repurposed décor from mixed sources and a palpable anti-slick, anti-corporate sensibility in favor of nostalgia for the 19th and early 20th centuries.

And if the Brooklyn look hasn’t arrived in your town, it’s coming.

There are 181 “Brooklyns” in the UK alone, according to the National Business Register. There’s a Brooklyn bar in Hong Kong and Brooklyn Steakhouse in Berlin (housed, naturally, in the city’s Dude Hotel). Advertisements for last year’s Brooklyn Mania festival at the department store Le Bon Marché in Paris featured the sub-culture’s platonic ideal man, with the requisite handlebar mustache, tattooed forearms and flashy bandages on his fingers. And beyond the exposed chipboard entrance of the Bedford-Stuyvesant café in Amsterdam, the Netherlands (home of the original Breukelen) a mural of an idyllic brownstowne-lined neighborhood occupies a whole wall.

The unmistakable Brooklyn look has surfaced in food packaging, design blogs, greeting cards, and even in the interiors of co-working spaces around the world.

Before Brooklyn’s bricolage trend took on around 2010, consumers were trained to invest in matching furniture sets, says Vern Yip, an Atlanta-based interior designer who used to appear on the HGTV show Trading Spaces. “At that time, it required a lot of money to plunk down at one time to pull all those things together,” he says.

“Now, buying things in sets is associated with the low end in the design world. Everything has sort of flipped. It’s like having a dining table with four, five different chairs and making it look cool and having mismatched plates.”

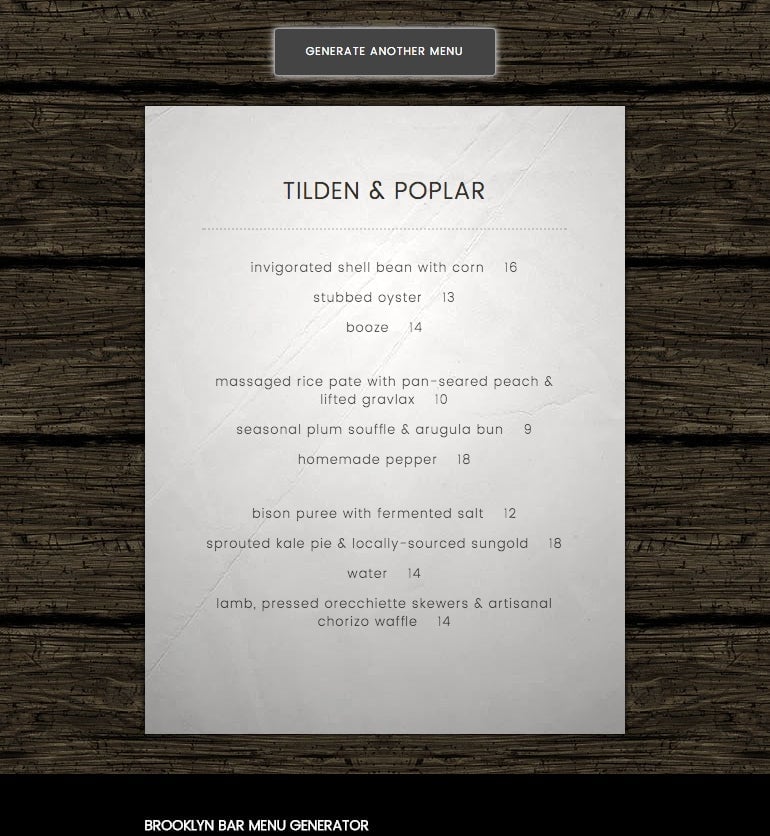

Once a style of independent expression and creative re-use, Brooklyn-the-aesthetic has become a commercial cover for overpriced consumer goods, parodied online by the likes of The Hipster Business Name Generator or the The Brooklyn Menu Generator. And even though most designers now bemoan the look’s clichés, its ability to attract money everywhere it appears fuels its appeal.

Designers hate it

Interior designers cringe at the Brooklyn look. “It always comes to the same formula, [real estate developers want] the warehouse aesthetic,” laments architect Matthias Hollwich. His firm Hollwich Kushner has encountered several developers who have asked for the Brooklyn look in hopes of attracting moneyed hipster tenants.

“Our answer is that we all have to be aware that the hipsters are starting to run out of warehouses and are not interested anymore in that kind of aesthetic because now it’s become mainstream.” he says. “Even Starbucks has absorbed this aesthetic quality.”

“I cringe any time someone applies a look universally—whether it’s the traditional look, the contemporary look, or the hipster look—because it shows a lack of sensitivity and creativity,” says Yip, who has penned a new book about finding one’s individual style.

Yip cautions against the over dependence on off-the-shelf props and themey decorations. “To me it removes the soul of the space and you can tell every time you enter a space and it feels vapid. You can tell when a designer just “turned it in” and didn’t give it a lot of thought.”

Even the hipster design’s originators Stephen Alesch and Robin Standefer (a.k.a. Roman and Williams) told the New York Times (paywall) in 2012 that they themselves were over aesthetic they helped popularize, notably through their design work for the Ace Hotel chain. “We hate heritage, now it’s on everything, even on Clorox bottles,” said Standefer.

Bankable Brooklyn

Despite criticism, many business owners believe that quoting the Brooklyn look is good for their bottom lines, justifying raised rents and that extra $3 for a latte that’s ”hand-crafted.”

Established restaurants are getting the hipster makeover. Traditional restaurants like Dickey’s Barbecue in Dallas, eateries in Toronto’s Chinatown and even the 47-year old roadside diner chain Cracker Barrel—in the guise of its new biscuit joint Holler & Dash—are embracing chalkboard menus and reclaimed wood look to attract the affluent, design-savvy millennial.

Before a liquor license snafu shut them down last year, even fast food chain Taco Bell operated under the hipster guise of US Taco Co. in Huntington Beach, California. With the reclaimed industrial lighted sign “EAT TACOS” above the counter, customers treaded on mismatched tile patterns and slurped shakes served in typically Brooklynish Mason jars.

The Brooklyn model also offers perks for scrappy upstart businesses, loosening the rules of how business is done. For the authors of the 2014 book Hipster Business Models, hipster business—inextricably entwined with the Brooklyn brand—means scrappy and inventive tinkerers, looking to monetize something they’re passionate about.

“Hipster businesspeople have also benefited from the fact that it is now more acceptable than ever before to pursue oddball ideas,” writes co-author Zachary Crockett. “Living in a van while operating a small business might now be seen as a ‘life-hack’; in the past, this lifestyle exemplified failure. A skilled person who makes fine leather wallets by hand is considered a craftsman; in prior eras, he could have likely been deemed a Luddite.” Meanwhile, the hackneyed Brooklyn bric-a-brac that design sophisticates love to hate project a familiar and reassuring guise for customers.

“In some ways, Brooklyn is the anti-Wall Street. It’s local, it’s dirty, it’s do-it-yourself,” said Ben Hudson, Brooklyn Brewery’s director of marketing to CNBC. The 29-year old brewery has harnessed Brooklyn’s cache around the world and tripled its sales in five years without the help of traditional advertising. Its quintessential Brooklyn-branded ale can now be ordered in bars from Seoul to Shanghai.

Beyond Edison bulbs

So does the commercial promise of the Brooklyn brand mean that are we all doomed to an eternity of plaid, fake distressed wood, and soulless typography?

Yip and Hollwich agree that there’s a kernel in the hipster mindset that’s worth saving—and evolving: ”What I love is the thought that you shouldn’t have to conform to societal standards when it comes to your aesthetic,” explains Yip. “Now it’s been so commercialized but I think the original point is really, really valid and really, really good: Don’t be afraid to make independent choices.”

Hollwich believes that the hipster’s tired aesthetic could evolve to new expressions. Instead of installing pre-aged lumber for example, he suggests choosing rapidly aging wood (like untreated lumber) that ages with people in buildings. He also predicts that the hipster Brooklyn’s new aesthetic expression will tend towards 1960’s Brutalism. ”You’re going to go much into aluminum panels and pre-cast buildings that are also raw and nondescript. It’s a whole new take on picking up on something that’s not appreciated by people in the society.”

“Many of these [hipster] elements are just decoration that people apply to tap into a certain level of nostalgia. We think it’s more interesting to trigger the emotion with new ideas,” he says. “A true hipster will have to reinvent himself.”