Ancient Egyptians’ 4,000-year-old strategy for dealing with an “argumentative superior”

Patience is a virtue. Don’t bug your partner about their weight. Try not to vex your boss. As a new translation of ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs reveals, the fundamental rules of human behavior have changed little in the last 4,000 years—and wisdom from the times of the pharaohs still rings wry and insightful today.

Patience is a virtue. Don’t bug your partner about their weight. Try not to vex your boss. As a new translation of ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs reveals, the fundamental rules of human behavior have changed little in the last 4,000 years—and wisdom from the times of the pharaohs still rings wry and insightful today.

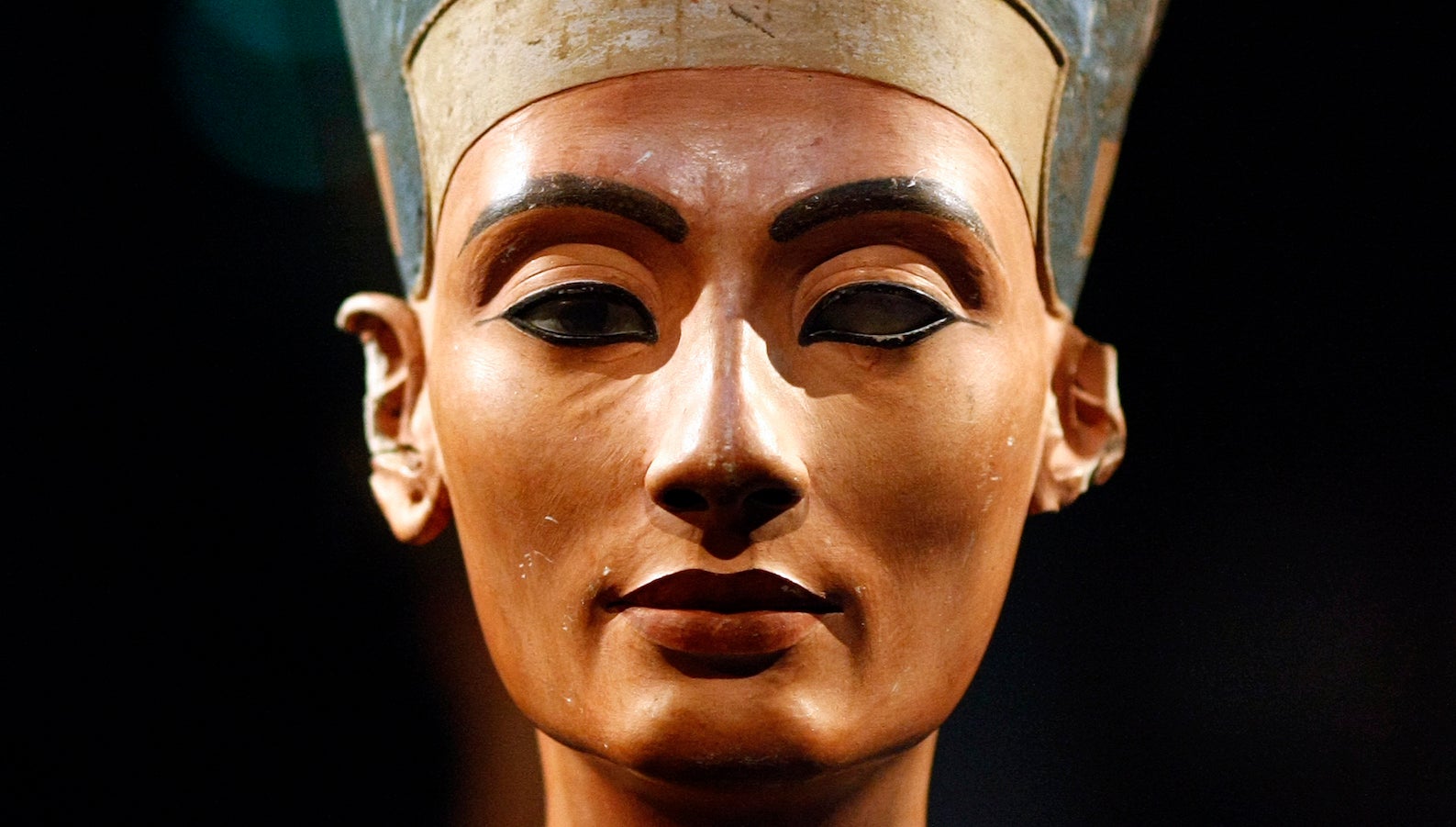

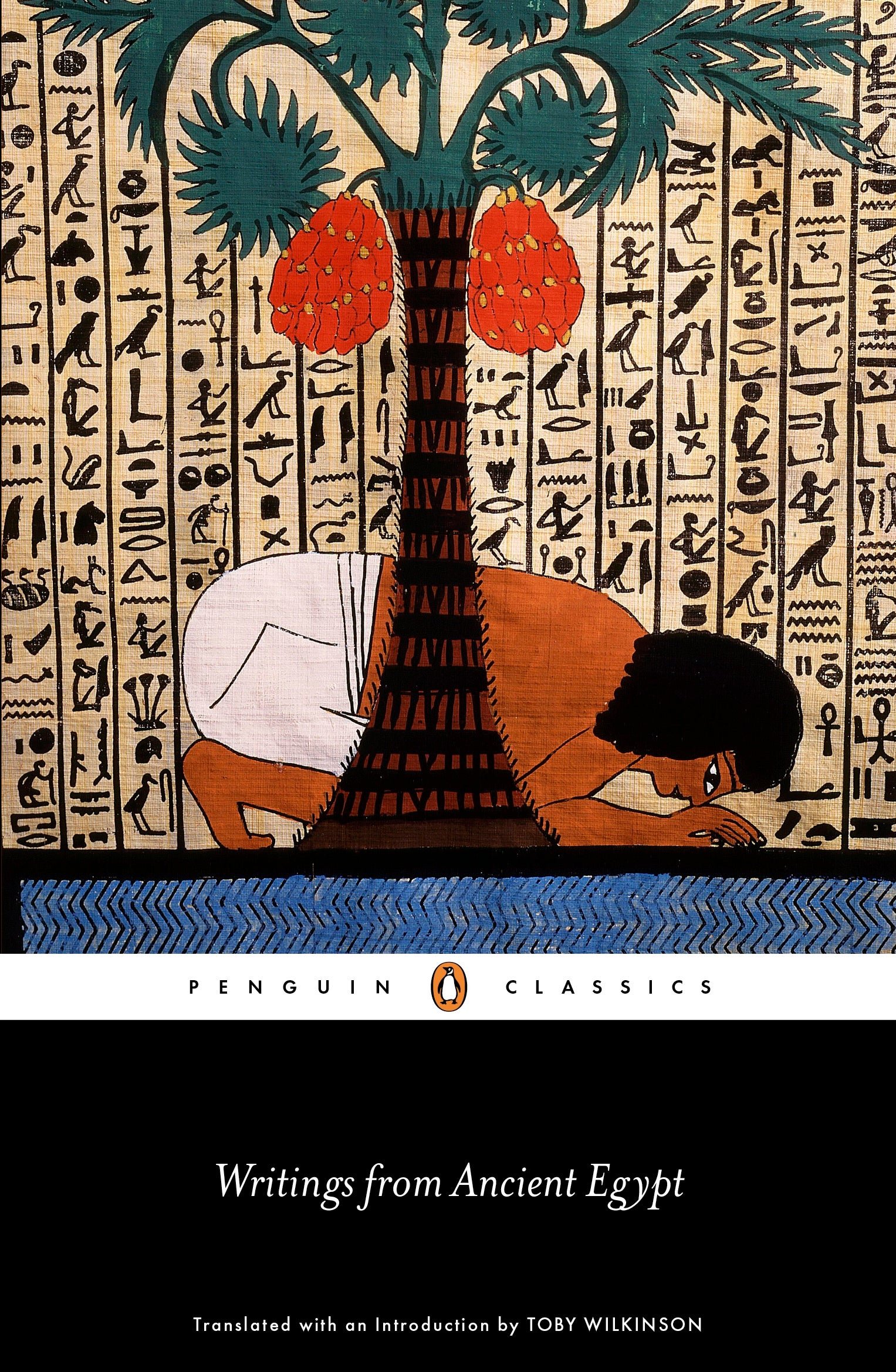

Writings from Ancient Egypt (Penguin Classics) is an anthology of millennia-old papyrus, letters, and stone carvings, selected and translated into sparkling contemporary English by Cambridge University Egyptologist Toby Wilkinson. Released in the UK on Aug. 24, the book aims to cast new light on writing from the ancient civilization. Egyptian art and artifacts are full of hieroglyphs, points out Wilkinson in his introduction, yet museum visitors rarely get to read the stories they tell.

This book offers a taste of the vast body of ancient Egyptian literature. In addition to glamorous accounts of war and royalty, it’s packed with extraordinarily personal tales of life and the social anxieties of the time.

The 1147 BCE will of a twice-married mother dictates leaving three adult children out of her inheritance because they took her for granted. A 2300 BCE memoir by a desert scout recounts traveling across Africa in search of new goods and novelties. And one particularly instructive text, titled Teaching of Ptahhotep, invites comparison to other ancient “how to get ahead” teachings by the likes of Sun Tzu and Machiavelli.

Composed around 1850 BCE, Teaching is a series of snappy maxims attributed to a 110-year-old pharaonic vizier. When you go to someone’s house for dinner, Ptahhotep counsels, eat whatever your host puts in front of you—and “don’t keep shooting him glances.”

Ptahhotep’s advice on how to deal with argumentative superiors, equals, and inferiors, is so applicable today that it’s easy to forget the text is thousands of years old:

First maxim: How to deal with an argumentative superior

If you come across a disputatious man in (the heat of) the moment,

Second maxim: How to deal with an argumentative equal

If you come across a disputatious man

Third maxim: How to deal with an argumentative subordinate

If you come across a disputatious man

Do not vent your anger against your opponent,

Ancient Egypt was extremely hierarchical, according to Wilkinson, so much of the translated life advice focuses on navigating social pitfalls. Repeatedly, Ptahhotep returns to a piece of eternal wisdom: When in doubt, hold your tongue.

In his 16th maxim, “How to deal with petitions,” Ptahhotep again offers a lesson on the power of listening—this time for managers.

If you are a leader,listen quietly to the plea of a petitioner.

Do not rebuff him from what he planned to say:

a victim loves to vent his anger

more than to achieve what he came for.

It’s not all about work and status. Matters of the heart (ib, in ancient Egyptian) get serious consideration, too. “A woman left to her own devices is like water: when she is argumentative, make a trough for her,” counsels Ptahhotep on how to give a wife space.

“It has been my aim in this book to convey the wit, wisdom, humanity, and sophistication of the ancient Egyptians, as reflected in their writings,” writes Wilkinson in an email. “Too many of the old translations treat the texts as examples of dead scholarship, rather than as texts penned by living, breathing, laughing, and crying men and women.”

Most English-language readers are already familiar with ancient literature from Greek and Roman authors like Plato, Virgil, Sappho, and Seneca. But despite the West’s long fascination with ancient Egypt, interest in literature from that place and time may have been stymied by a lack of translators, and by the fact that ancient Egyptian writers were often anonymous. ”Pharaonic culture valued perfection within an established tradition over individual creativity,” Wilkinson writes, which makes it hard to identify “favorite” ancient writers or to celebrate great literary talent.