A US state wants to scrap traditional voting in favor of a less polarizing election system

Something truly radical could happen on November 8, and it has nothing to do with electing the first female, or perhaps the first reality television star, as president. It’s the introduction of a better, fairer voting system altogether—at least on the state level.

Something truly radical could happen on November 8, and it has nothing to do with electing the first female, or perhaps the first reality television star, as president. It’s the introduction of a better, fairer voting system altogether—at least on the state level.

When Mainers go to the polls on election day this year, they will choose whether to make their state the first in the US to adopt what’s called “ranked-choice” voting. The new method, which would apply to Maine’s federal and state elections, empowers voters to rank candidates in terms of preference, instead of betting on just one.

If state voters choose in favor of Question 5, as the ballot measure (pdf) is known, they could upend their traditional voting system in a good way: Unlike the current system, ranked-choice voting rewards moderates, helps third-party candidates compete, and discourages negative campaigning.

The most recent poll on Maine’s proposed system was done in March, but it suggested a strong swell of support behind the measure (pdf, p.9) at the time.

The risks of plurality voting

At every political level, here’s how Americans usually cast their ballots: Each voter picks one candidate, and the candidate with the most votes (a “plurality”) wins. But those candidates might not have the majority of votes (i.e. more than half).

Consider the 2016 Republican primary vote in South Carolina. If you counted only voters’ first choices, Donald Trump clearly won by plurality. But he won only about one-third of the total vote—which means the majority of voters didn’t support Trump.

Some think the plurality voting system tends to push candidates to ideological extremes. What usually happens is that whoever can motivate the most people to hit the polls wins. And the most enthusiastic voters often tend to be those most driven by extreme world views.

Candidates who are less ideologically extreme might not attract voters who are as committed. And moderate candidates who clump around the middle of the ideological spectrum are more likely to split each others’ votes—allowing ideological purists to divide and conquer. Even if a majority of South Carolina primary voters couldn’t stand him, Trump wins as long as those voters are divided over which candidate they support.

Another potential problem with plurality voting is that it makes lots of voters not vote for their first choice—precisely because they’re worried about vote-splitting. A woman we spoke with in South Carolina days before the state’s primary told us that she detested Trump and really liked John Kasich, the Ohio governor who was relatively unknown in southern states. However, she was worried that voting for an underdog would mean her “vote wouldn’t count.” She wound up voting for Rubio, a candidate she thought stood a chance of defeating Trump.

What if instead of voting for either Kasich or Rubio, she could have voted for both of them—and indicated how much she didn’t like Trump?

How ranked-choice voting works

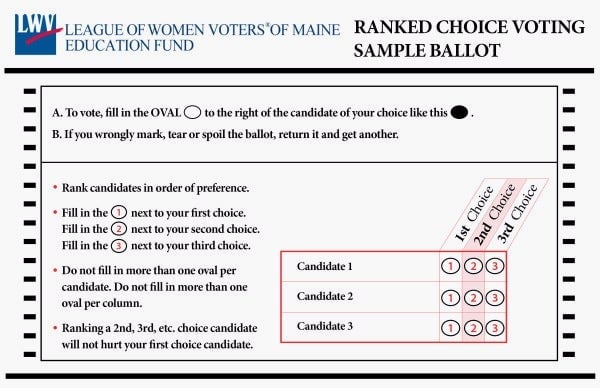

That’s what Maine is proposing to do. Ranked-choice voting (which is sometimes called instant-runoff voting) would require voters to rank candidates as their first choice, second choice, and so on.

Once the first choices are tallied up, if no one has won the true majority of the vote (50.1%), the last-place candidate is knocked out. Voters who picked that candidate as their top choice now have their second choices tabulated. This keeps happening until a candidate finally earns a majority.

Now in our South Carolina example, it’s obviously impossible to know how things would have shaken out if ranked-choice voting had been used. But to illustrate the possibilities, here’s a completely hypothetical, back-of-envelope illustration of how the state’s primary vote could have gone:

Jeb Bush would have been the first major candidate eliminated. Let’s assume all of his votes go to Kasich, because all the people who ranked Bush first listed Kasich second. In the next round of voting, no one has anything close to a majority, so Carson gets booted. We’ll suppose that half of his voters’ second choices turn out to be Trump, and the other half marked Ted Cruz as their second pick. Kasich is knocked out next, giving all of his votes to Rubio. When Cruz is cut, Trump and Rubio split his votes. As you can see, there’s a chance Rubio—a far better-liked candidate than Trump or Cruz—could have emerged the victor.

Why Maine’s Question 5 matters

Maine wouldn’t be the first to adopt this system. Australia, Ireland, Papua New Guinea, Hong Kong and several other countries or territories use it. So do many US cities—including Minneapolis and St. Paul, most of the Bay Area, as well as Portland, ME, Hendersonville, NC, and Takoma Park, MD.

But the Maine ballot measure is a big development. If Question 5 passes, Maine will be the first state to use the ranked-choice system in state and congressional elections. In other words, the methodology will be used not only for state legislature and gubernatorial elections, but also to pick Maine’s US senators and Congressional representatives. (Question 5 does not affect presidential elections.) The new system would roll out in 2018, in order to permit careful implementation.

Maine seems particularly in need of a new voting system. Thanks to its long-standing zeal for third-party candidates and independents—which mean that three or more candidates run against each other—since 1974, only two Maine governors have won with a majority. Some data suggest that if Maine had used ranked-choice voting in 2014, independent gubernatorial candidate Eliot Cutler would have beaten Republican incumbent Paul LePage, Maine’s divisive and controversial governor, who made headlines last week for launching a racist tirade.

The downside of complicated ballots

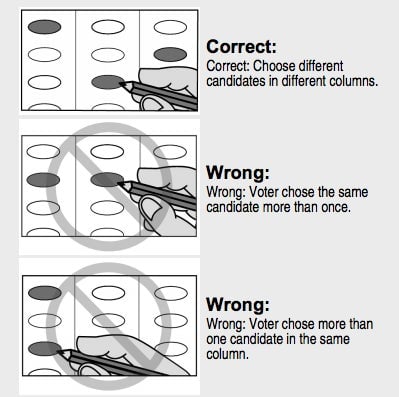

Ranked-choice voting is not without its critics. Jason McDaniel, a political science professor at San Francisco State University, argues that ranked-choice voting makes ballots too complicated for some voters, driving down participation. His research comparing voter turnout in San Francisco before and after the city adopted ranked-choice voting suggests declining participation among young voters, African Americans and less educated voters. It also may have increased the rate of ballots disqualified due to error—a trend that disproportionately affected votes by African Americans and the elderly in his study.

“My conclusion is that, in San Francisco, ranked-choice voting widens the gulf between the haves and the have-nots when it comes to participating in the democratic process,” writes McDaniel in the Bangor Daily News.

Some voters also fail to fill in their ranking choices correctly. This is why in Portland’s mayoral 2011 election, the winner of the 15-candidate contest ultimately triumphed without a majority (he won only 46% of all votes cast). Still, that was the first year Portland used the new system. It’s likely these problems will wane as people grow used to the new ballots.

On the plus side, ranked-choice voting rewards candidates who appeal to a broader swath of the electorate than just their base. It helps diminish the “spoiler effect,” where a third-party candidate splits the vote with one candidate, launching their opponent to a victory (e.g. Ralph Nader, Al Gore, and George W. Bush in the 2000 election).

At the same time, it gives popular third-party candidates like Maine’s Cutler a much better shot, which is why some political scientists think this alternative voting system could boost voter turnout, not curb it. Think of all the people who grouse about the two-party monopoly, and sit out elections because the third-party and independent candidates they like don’t stand a chance. Maybe they’ll become more engaged in the process if there’s a real chance to put someone they like in office—or at least to know that their vote will finally count.