A photographer’s brilliant crusade to challenge the boundaries between science and art

There are few things that make Rosamund Purcell’s heart leap as much as prehistoric fish swimming in formaldehyde. For much of her career, the revered but relatively unknown 74-year old American photographer of natural curiosities has been digging through natural history museums, taxidermy galleries, and junk yards in search of the sublime.

There are few things that make Rosamund Purcell’s heart leap as much as prehistoric fish swimming in formaldehyde. For much of her career, the revered but relatively unknown 74-year old American photographer of natural curiosities has been digging through natural history museums, taxidermy galleries, and junk yards in search of the sublime.

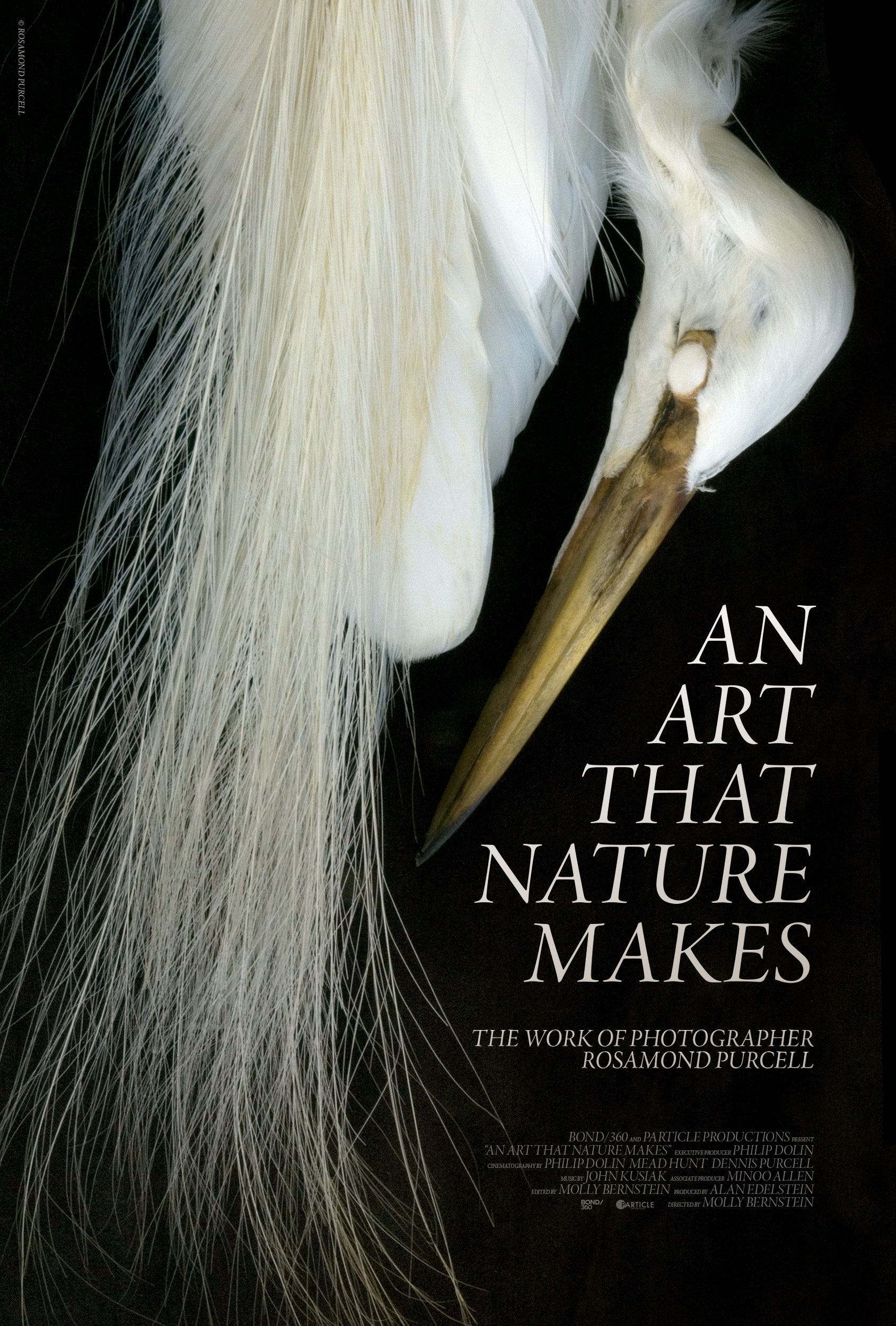

As the new film An Art That Nature Makes portrays, Purcell has spent a lifetime demonstrating how lab photographs of skulls, skeletons, and animal skins don’t have to be so cold and literal.

With no extraneous special effects or elaborate lighting rigs, Purcell casts strange objects and dead animals in hauntingly beautiful narrative scenes. In Monkeys with Raised Arms, she takes eight stuffed monkeys from the Harvard Museum’s collection and poses them as a desperate crowd with arms raised, mouths agape, their cotton-ball eyes looking up the sky in dread.

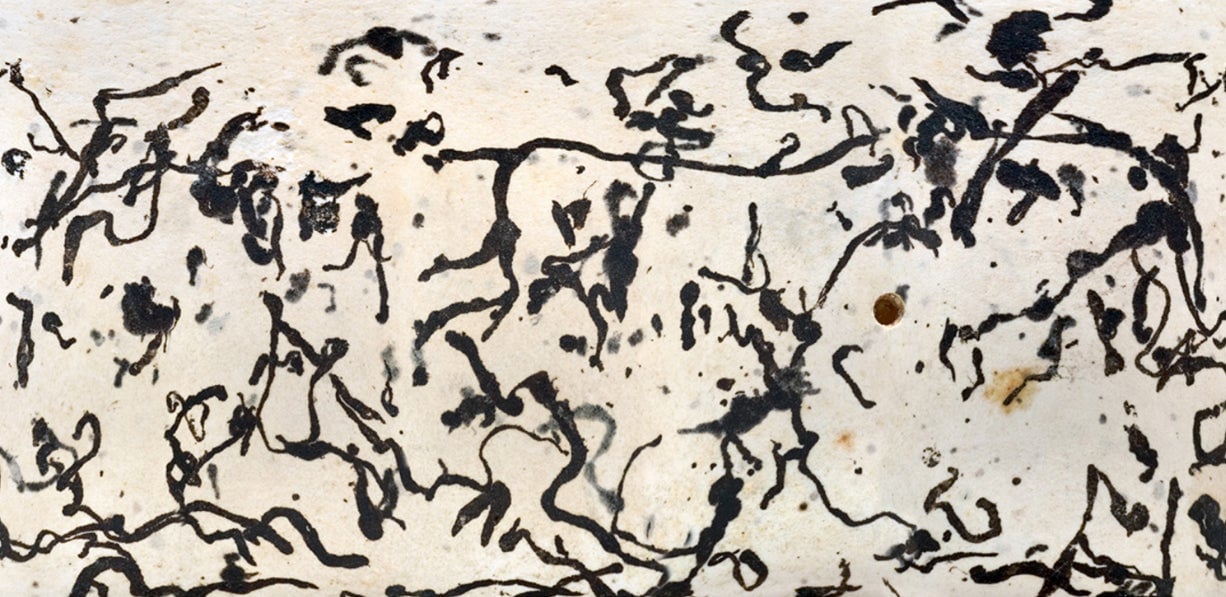

Noting the calligraphy-like markings on a 100-year old murre egg, Purcell creates a mercator projection image of its surface. The result is reminiscent of a drip painting by Jackson Pollock.

Upon inspecting a piece of wood eaten up by mollusks, Purcell gets into a philosophical debate with a malacologist. “Can’t you look at this surface as something with an aesthetic transporting quality?” she asks. When the mollusk expert appears unconvinced, Purcell demonstrates her point by zooming into the shipworms’ paths and producing an abstract image that evokes the work of surrealist painter Yves Tanguy.

A longtime collaborator of the late paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould, Purcell’s art flourished with her frequent dalliances with scientists and naturalists. “I’m much more comfortable talking to and collaborating with somebody in a field who has completely different training, point of view, and vocabulary,” says Purcell in the film. ”It’s hybrid vigor.”

Though her work has been featured in some 20 books and scientific journals, Purcell’s oeuvre is little known outside of a small circle of admirers and subscribers to National Geographic or fine art photography journals. Unlike fellow documenter of fowl and fauna James Audubon, there are no dainty boxed cards or museum calendars of Purcell’s work. “Rosamond’s work is largely interdisciplinary, so perhaps it tends to fall between the cracks of the many disciplines that her work bridges,” says Molly Bernstein, director of An Art That Nature Makes. “Hopefully the film gives the viewer access to this kind of ‘crossover’ conversation by exploring Rosamond’s working methods and her point of view.”

An Art That Nature Makes premieres at Laemmle’s Monica Film Center in Los Angeles on September 2.