“I got scammed”: A tech worker’s awful story shows the gap between idealism and reality in Silicon Valley

Come to Silicon Valley, California. Build something important. Get rich! It’s a narrative that has attracted thousands. But for some, it turns into a nightmare.

Come to Silicon Valley, California. Build something important. Get rich! It’s a narrative that has attracted thousands. But for some, it turns into a nightmare.

That appears to be the story of Penny Kim, a former marketing director at a company called WrkRiot (before that, JobSonic and 1for.one). The company described itself on a Facebook page that has since been taken down as “disrupting” the job search by offering “just jobs”: “No more games. No more sponsored jobs that don’t apply to you. No more unfairness in the job market.”

For all the company’s self-professed straight talk, Kim tells a devastating tale of alleged deceptions, including forged wire transfer receipts, late paychecks, and lies from executives. This week, she wrote about her experience working at the company in a Medium post titled ”I Got Scammed By A Silicon Valley Startup.”

“It was traumatic for me,” Kim tells Quartz in an interview. “My main goal [in publishing the post] was to show people the other side of what Silicon Valley and startups are like. Everyone has hopes and dreams. I did. I moved out to California to achieve that dream.”

The world is captivated by the success stories of people like Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg, and many chase their own entrepreneurial ambitions in Silicon Valley. The mythology of the Valley is that it’s a place where a few people can make a huge difference, and maybe hit the jackpot in the process. But the optimism and idealism behind startups can mask deeper problems with those who run them.

In retrospect, Kim realized there were red flags about the company all along, but she pushed aside her concerns. She was spurred on by the company’s seeming credibility—built upon the established reputations of investors and advisors involved, as well as the assurances of the CEO. ”There’s no way a startup I found on Angel.co is going to screw me over,” she says she thought to herself during the interviewing process.

The company and its management were left unnamed in Kim’s post, but archived versions of WrkRiot’s team page and biographies match the work profiles of executives described in Kim’s piece. Kim also confirmed the company’s name in an interview after WrkRiot seemed to acknowledge the post on its Facebook account.

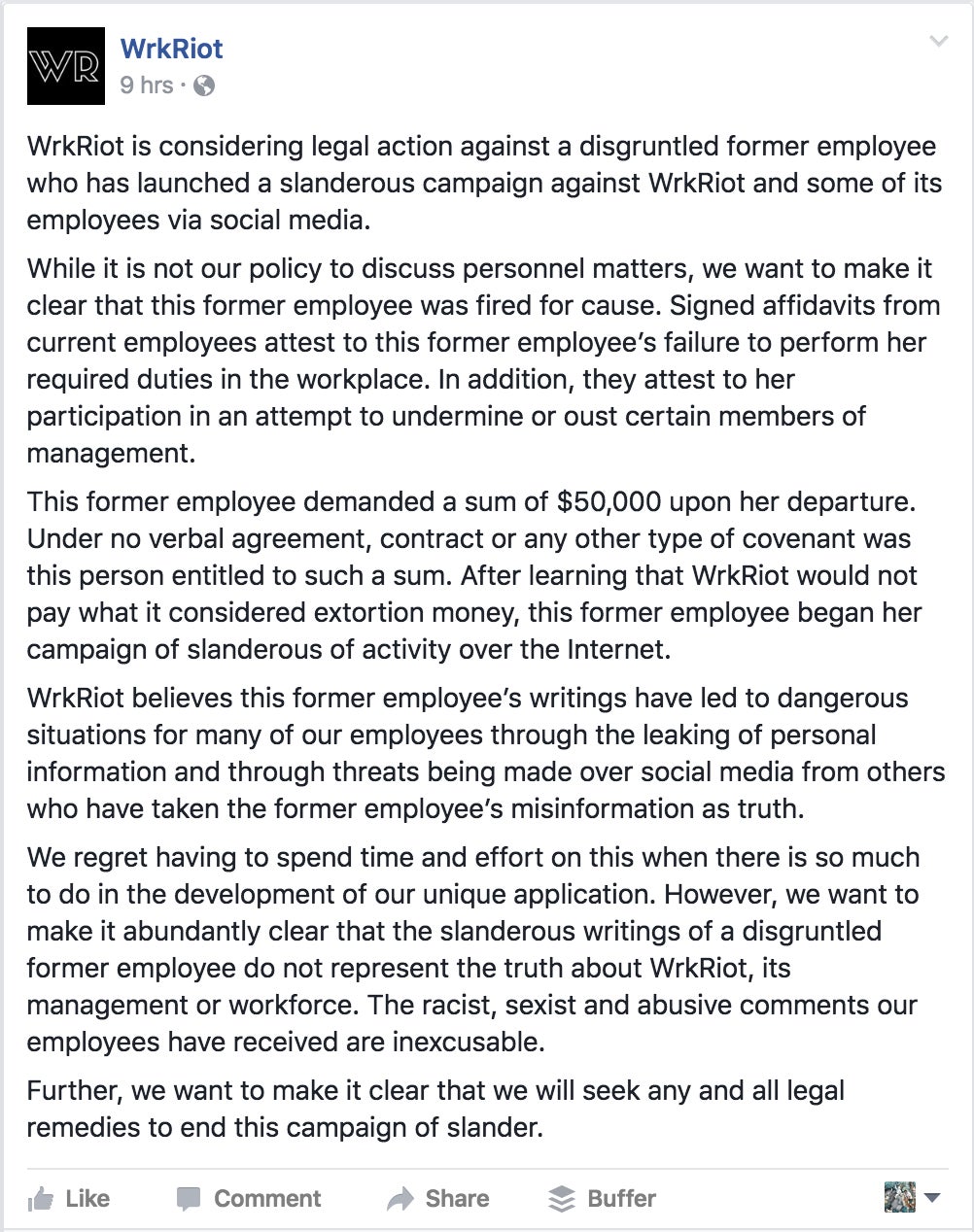

WrkRiot’s official website and several social media posts have been taken down, but WrkRiot’s official Facebook account posted an apparent rebuttal (also since removed) to Kim’s piece the same day, promising to employ “all legal remedies to end this campaign of slander.” (Technically, a written defamation would be libel, not slander.)

Kim’s chronicle of a company spiraling into dysfunction has riled the tech community, and elicited a social media response similar to that a letter from an unhappy former Yelp employee did earlier this year.

Here’s the story Kim lays out in her Medium post: In May 2016, after three interviews, she says she accepted the role of marketing director at 1for.one, one of WrkRiot’s earlier incarnations. From the beginning, things didn’t seem quite right, she says. The CEO, Isaac Choi, hired one of her direct reports without consulting her. A promised $4 million marketing budget never materialized. At investor meetings, the co-founders “talked about themselves, their connections, and their qualifications for 30 minutes” rather than the product, which they touted as the next “Credit Karma of LinkedIn.”

The software engineering team was largely made up of young Chinese employees relying on visas sponsored by the company to remain in the US, Kim says. According to Kim, an employee loaned $50,000 of his savings to the CEO, and the chief technical officer lent another $230,000 to the company to cover payroll. Kim’s first paycheck was late, and other employees started missing paydays after WrkRiot parted ways with its payroll administrator ADP.

After repeated inquiries about salaries, Kim alleges, Choi sent forged Wells Fargo wire transfer receipts to 17 employees, and told them that if the money wasn’t in their accounts that it was their responsibility to follow up with their banks. Kim ended up filing wage claims with the state of California as the paychecks stopped coming.

WrkRiot CEO Isaac Choi fired Kim in mid-August, she writes in her post, claiming that she tried to “kill the company by turning the team against him by encouraging them to file wage claims.” Kim said she later found out another employee was acting as a “mole,” relaying her and other colleagues’ complaints to the CEO.

Choi, who did not respond to requests for comment through the company’s Facebook or LinkedIn accounts, described his work experience on Crunchbase as the former CEO of C2S Mining Group, a cofounder of SavantLingo, and an analyst at JP Morgan.

Kim claims Choi fired her without cause and owes her back wages, a promised $10,000 relocation bonus, and three months of severance worth $50,000, as negotiated in her contract (Kim declined to share her contract with Quartz). The company eventually paid her back wages, although not her bonus or severance, she says. In a Facebook post, WrkRiot claims there was no verbal agreement or contract that she was owed $50,000 (it did not address the $10,000 bonus she says she’s owed).

A series of former employees, advisors, and even the the company’s former CTO have since denounced WrkRiot and its leadership, in particular Choi. The company’s currently listed chief marketing officer, who replaced Kim, also appears to have written a brutal two-part series, “How Working At a ‘Start Up’ Almost Killed Me.”

LinkedIn’s former director of engineering, Daniel Tunkelang, wrote on Medium that he had cut ties with WrkRiot, apologizing “to anyone who took the company more seriously because of my association with them,” and saying he himself had overlooked the red flags. “I should have gotten to know the company and its leadership better before associating myself with them and lending them my credibility,” he wrote. “Lesson learned.”

The company’s former CTO, Al Brown, responded on HackerNews on Aug. 29, confirming the facts of Kim’s account and claiming he too had been deceived. Quartz verified his HackerNews user albertcbrown in an interview with Quartz on Aug. 30. “I was conned as much as anyone in this company if not more,” Brown told Quartz. “[Choi] is actually very convincing. The stories he came up with were always very believable.”

Brown officially severed ties with the company on Aug. 29. He said he had been unable to confirm Choi’s personal story after talking with family members and colleagues. The development team he led, most of whom are on F1 visas, must return back China if they can’t find new jobs quickly. He is now owed expenses, August office rent, back pay, and the $230,000 bridge loan. “It’s bad,” he said.

“I wasn’t thinking of really doing deep due diligence on my partner. I took him at this word,” said Brown who was introduced to Choi by a trusted colleague. ”I really wanted to believe in the dream and him….It’s really hard to face the fact it might not be true.”

WrkRiot’s story appears to be one of willful deception and wildly misplaced trust. Friends and family members introduced the company’s executives. Employees, up until very recently, seemed to still have faith in the CEO’s promises. Advisors had taken the company’s management at its word. It seems a mounting wave of mistakes, coverups, and outright deception led to the company’s current predicament.

This looks naive in retrospect, but it is how much of Silicon Valley operates. Despite claims of due diligence, many deals and company foundings are brokered largely on the strength of personal relationships, especially within trusted social networks. These recommendations remain a valuable currency in the valley, despite the reoccurrence of apparent horror stories like WrkRiot.

That will likely be little consolation to the people involved with WrkRiot. Kim has since moved back to Dallas as she looks for another job. “It’s not a happy ending,” she says, “and it’s not great for anyone.”

She still dreams of working in California, but is now looking for roles at more established companies. For the time being, she’s trying to readjust to her post-startup life. “I feel like I am a whistleblower,” she says. “I’m still going through this hell. I still have to face retaliation.”