Harvard research highlights six ways to trick your brain out of procrastination

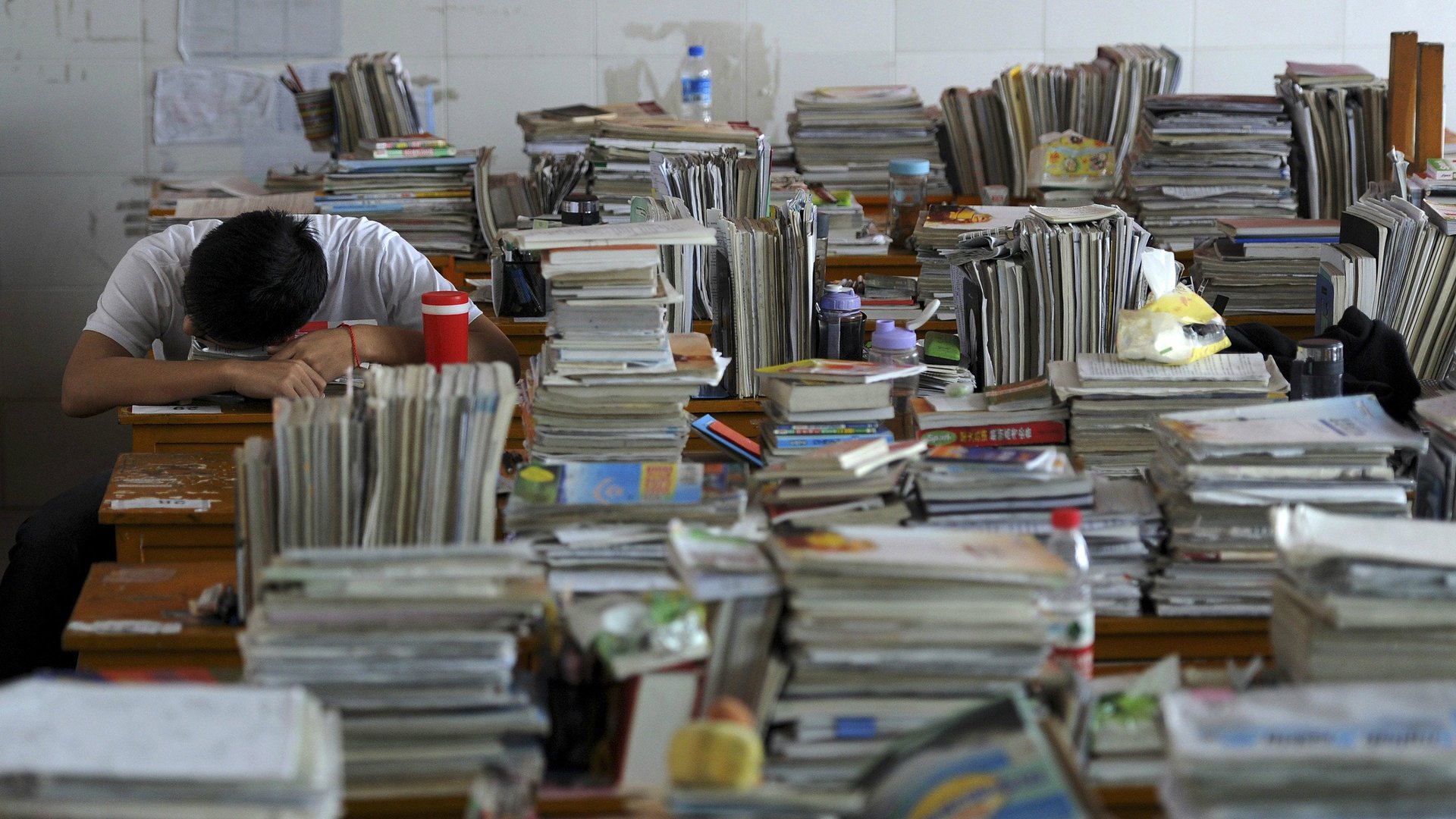

People procrastinate for many reasons, but the result is always the same: they rush to get the task done at the last minute, or miss the deadline. Even though it feels frustrating to procrastinate, people still continue this bad habit. Why?

People procrastinate for many reasons, but the result is always the same: they rush to get the task done at the last minute, or miss the deadline. Even though it feels frustrating to procrastinate, people still continue this bad habit. Why?

According to Caroline Webb in the Harvard Business Review, our brains are programmed to put off tasks. Webb shows research from UCLA proving that the allure of near-term gain almost always outweighs the attraction of future reward. Given the choice between concrete and more abstract ideas, our brain naturally sides with more material notions.

But just because our brains are seemingly working against us doesn’t mean we can’t overcome procrastination. Instead, it should inspire us to work at the task even more—it isn’t a personal flaw, but a part of our natural make-up that can be re-trained.

Without further ado, here is the research-backed guide to get started:

Find an accountability partner

When we share our goals with someone else, it creates social pressure, but unlike the peer pressure we faced in high school, this type can lead to success.

Sharing your goals with a partner can create a system where you have a cheerleader and walking living reminder to stop procrastinating. In fact, according to Webb’s research, experts have found that we instinctively want to be respected by peers, and are more likely to reach our goals this way.

So when you have a task at work to complete, tell someone when you will finish it. If you tell a client or employee exactly when you’ll get something done, your brain will feel more obligated to actually do it. Even better, if you’re trying to accomplish a big-ticket item, harness the power of mentorship to boost your accountability and success.

Make the cost of action feel smaller

Identify the first step. Sometimes we’re just daunted by the task we’re avoiding. We might have “learn French” on our to-do list, but who can slot that into the average afternoon? Caroline Webb says the trick here is to break down big, amorphous tasks into baby-steps that don’t feel as painful. Even better: identify the very smallest first step, something that’s so easy that even your present-biased brain can see that the benefits outweigh the costs of effort.

So instead of “learn French” you might decide to “email Nicole to ask advice on learning French.” Achieve that small goal, and you’ll feel more motivated to take the next small step than if you’d continued to beat yourself up about your lack of language skills.

Tie the first step to a treat

We can make the cost of effort feel even smaller if we link that small step to something we’re actually looking forward to doing. In other words, tie the task that we’re avoiding to something that we’re not avoiding. For example, you might allow yourself to read lowbrow magazines or books when you’re at the gym, because the guilty pleasure helps dilute your brain’s perception of the short-term “cost” of exercising. Likewise, you might muster the self-discipline to complete a slippery task if you promise yourself you’ll do it in a nice café with a favorite drink in hand.

Remove the hidden blockage

Sometimes we find ourselves returning to a task repeatedly, still unwilling to take the first step. We hear a little voice in our head saying, “Yeah, good idea, but . . . no.” At this point, we need to ask that voice some questions, to figure out what’s really making it unappealing to take action. This doesn’t necessarily require psychotherapy. Patiently ask yourself a few “why” questions—”why does it feel tough to do this?” and “why’s that?”—and the blockage can surface quite quickly. Often, the issue is that a perfectly noble competing commitment is undermining your motivation.

For example, suppose you were finding it hard to stick to an early morning goal-setting routine. A few “whys” might highlight that the challenge stems from your equally strong desire to eat breakfast with your family. Once you’ve made that conflict more explicit, it’s far more likely you’ll find a way to overcome it—perhaps by setting your daily goals the night before, or on your commute into work.

Trust yourself to start now

Once you’ve figured out what’s keeping you from taking action on a specific task or project, it’s time to get over your fear. Webb’s research shows that we’re more likely to perform a cost-benefit analysis on something new, but are far less likely to weigh the potential disadvantages of maintaining the status quo. This omission bias can keep us from doing things better just because it means doing something differently.

Get over this fear by using the 70% rule from the Marine Corps: As long as you have 70% of the information to make a decision, 70% of the resources to complete the project, and you’re 70% sure you’ll succeed, then you’re ready to go. The heart behind the 70% rule is that it’s impossible to be fully prepared for anything. Trust your gut and get started.

Focus on the results of procrastination

Mark Twain once said, “Never put off until tomorrow what you can do the day after tomorrow.” Don’t listen to him!

Instead, focus on what will happen if you put off a task or project until the last minute. You might have an emergency come up causing you to miss the deadline. The result may be that you miss out on a good deal or damage your professional reputation. Your client may feel you provided poor customer service, which could also affect your reputation and ability to obtain future work.

As you think more about the negative effects of putting off a task, you’ll be more motivated to avoid those effects and get the job done. According to Webb, Psychologists call this a prevention focus, because most people seek to avoid negative consequences even more than they aim to receive positive results. This mindset will keep you pushing on even when you want to quit or put the job off to another day.

Accept that procrastination is a natural part of who you are, but just like anything else, you also that you have the power to retrain your brain and overcome it with these practical steps. L.M. Heroux said, “Stop talking. Start walking.” I’d like to alter that advice just a bit and say to you, “Stop reading. Start succeeding!”

This post originally appeared at Medium.