How non-English speakers are taught this crazy English grammar rule you know but have never heard of

English grammar, beloved by sticklers, is also feared by non-native speakers. Many of its idiosyncrasies can turn into traps even for the most confident users.

English grammar, beloved by sticklers, is also feared by non-native speakers. Many of its idiosyncrasies can turn into traps even for the most confident users.

But some of the most binding rules in English are things that native speakers know but don’t know they know, even though they use them every day. When someone points one out, it’s like a magical little shock.

This week, for example, the BBC’s Matthew Anderson pointed out a ”rule” about the order in which adjectives have to be put in front of a noun. Judging by the number of retweets—over 47,000 at last count—this came as a complete surprise to many people who thought they knew all about English:

That quote comes from a book called The Elements of Eloquence: How to Turn the Perfect English Phrase. Adjectives, writes the author, professional stickler Mark Forsyth, “absolutely have to be in this order: opinion-size-age-shape-colour-origin-material-purpose Noun. So you can have a lovely little old rectangular green French silver whittling knife. But if you mess with that order in the slightest you’ll sound like a maniac.”

Mixing up the above phrase does, as Forsyth writes, feel inexplicably wrong (a rectangular silver French old little lovely whittling green knife…), though nobody can say why. It’s almost like secret knowledge we all share.

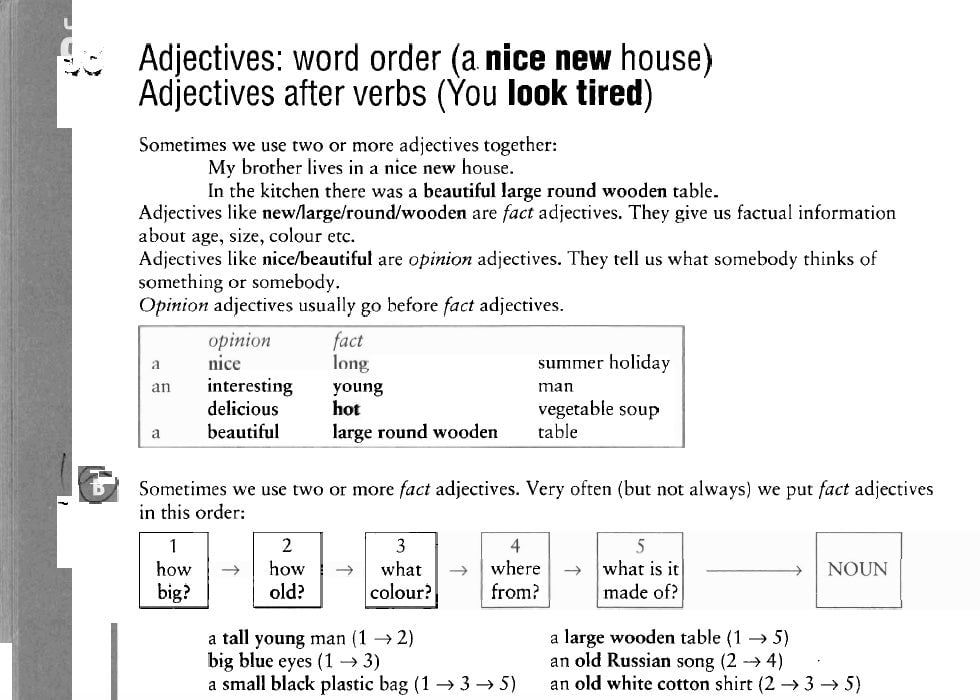

Learn the language in a non-English-speaking country, however, and such “secrets” are taught in meticulous detail. Here’s a page from a book, published by Cambridge University Press, used regularly to teach English to non-native speakers. An English teacher in Hungary sent it to us.

The book lays out the adjective order in the same way as Forsyth’s surprising illumination. Hungarian students, and no doubt those in many other countries, slave over the rule, committing it to memory and thinking through the order when called upon to describe something using more than one adjective.

The fact is, a lot of English grammar rules only come as a surprise to those who know them most intimately.

Learning rules doesn’t always work, however. Forsyth also takes issue with the rules we think we know, but which don’t actually hold true. In a lecture about grammar, he dismantles the commonly held English spelling mantra ”I before E except after C.” It’s used to help people remember how to spell words like “piece,” but, Forsyth says, there are only 44 words that follow the rule, and 923 that don’t. His prime examples? “Their,” “being,” and “eight.”