McDonald’s to Costco: You’re too cheap for us

McDonald’s and Costco would seem to have a lot in common, what with their relentless pursuit of cost-conscious consumers in the name of value.

McDonald’s and Costco would seem to have a lot in common, what with their relentless pursuit of cost-conscious consumers in the name of value.

But this month, the fast-food giant snubbed the US warehouse shopping club, dropping it from among two dozen or so competitors, consumer-product companies and retailers that McDonald’s uses to assess executive pay.

The reason McDonald’s gave in its most recent proxy filing? Unspecified but “general differences in compensation structure and philosophy” with Costco.

McDonald’s didn’t offer further explanation, but a look at the companies’ actual pay practices offers a strong contrast.

Last year, McDonald’s paid outgoing chief executive James A. Skinner $17.1 million in salary, bonuses and equity, plus another $10.6 million for stepping down in July. Costco, by contrast, paid its CEO, W. Craig Jelinek, $4.8 million. Over the last five years, McDonald’s has paid its CEO at the time an average of $13.4 million. Costco has paid an average of $3.4 million.

Put another way, if McDonald’s had paid its CEO like Costco does, the company could used the savings to buy one of those dollar-menu breakfast burritos for every child in New York City’s public schools—every month of the school year.

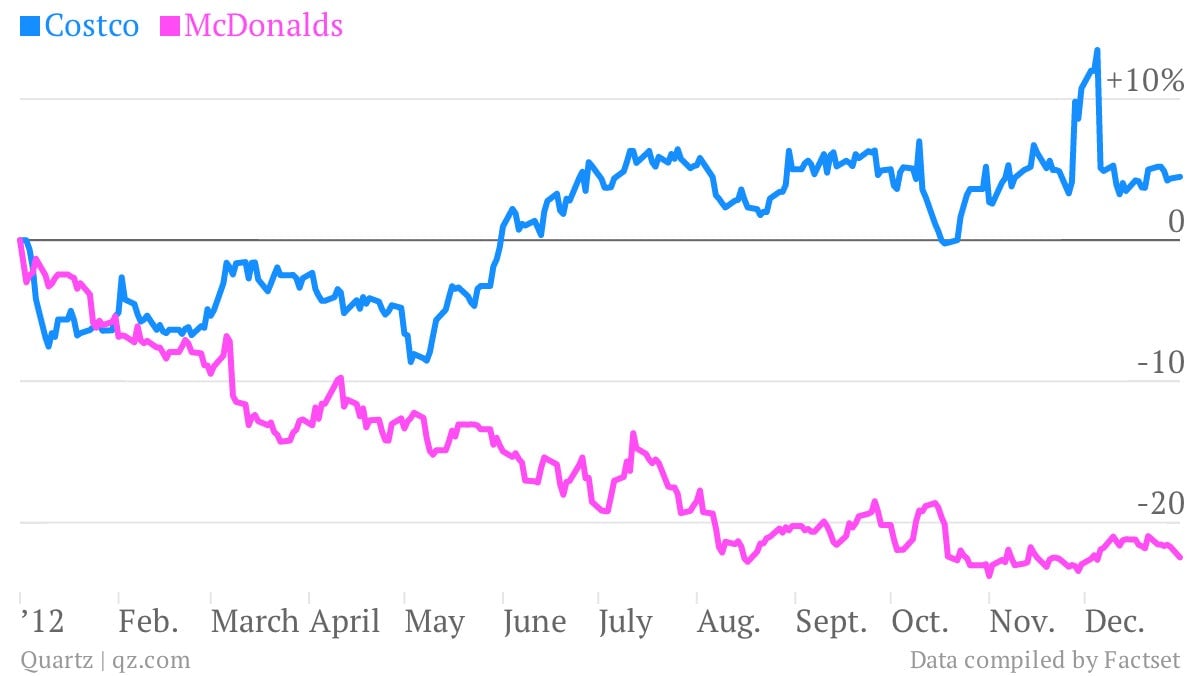

And performance? McDonald’s shares have trailed other restaurant companies by nearly three percentage points over the last five years, while Costco has beat other discount stores by just over a percentage point, according to data from Morningstar.com.

A stock chart for last year tells that part of the story even more clearly:

Peer groups in general have been coming under renewed scrutiny recently by corporate-governance researchers and activists. For years, companies were thought to be stacking the lists to make their own executives’ compensation look middle-of-the-pack, and the Securities and Exchange Commission required beefed-up disclosure by US-listed companies. More recently, researchers at the University of Delaware have suggested that the very act of benchmarking CEO pay to a peer group tends to drive compensation up, while divorcing it form pay structures lower down the company’s hierarchy.