Prejudice against ethnic-sounding names forces people to choose between their identities and success

Our name is like an elongated shadow attached at our heels. A tenacious sign of identification, it is intimately connected with our identification. While our first name is given to us lovingly and tenderly by our parents (or parent surrogates), our surname connects us to our ancestral history, our lineage, our clan. For most of us, a close association develops between our name and the person we are, such that the sound of our name reverberates deep within us.

Our name is like an elongated shadow attached at our heels. A tenacious sign of identification, it is intimately connected with our identification. While our first name is given to us lovingly and tenderly by our parents (or parent surrogates), our surname connects us to our ancestral history, our lineage, our clan. For most of us, a close association develops between our name and the person we are, such that the sound of our name reverberates deep within us.

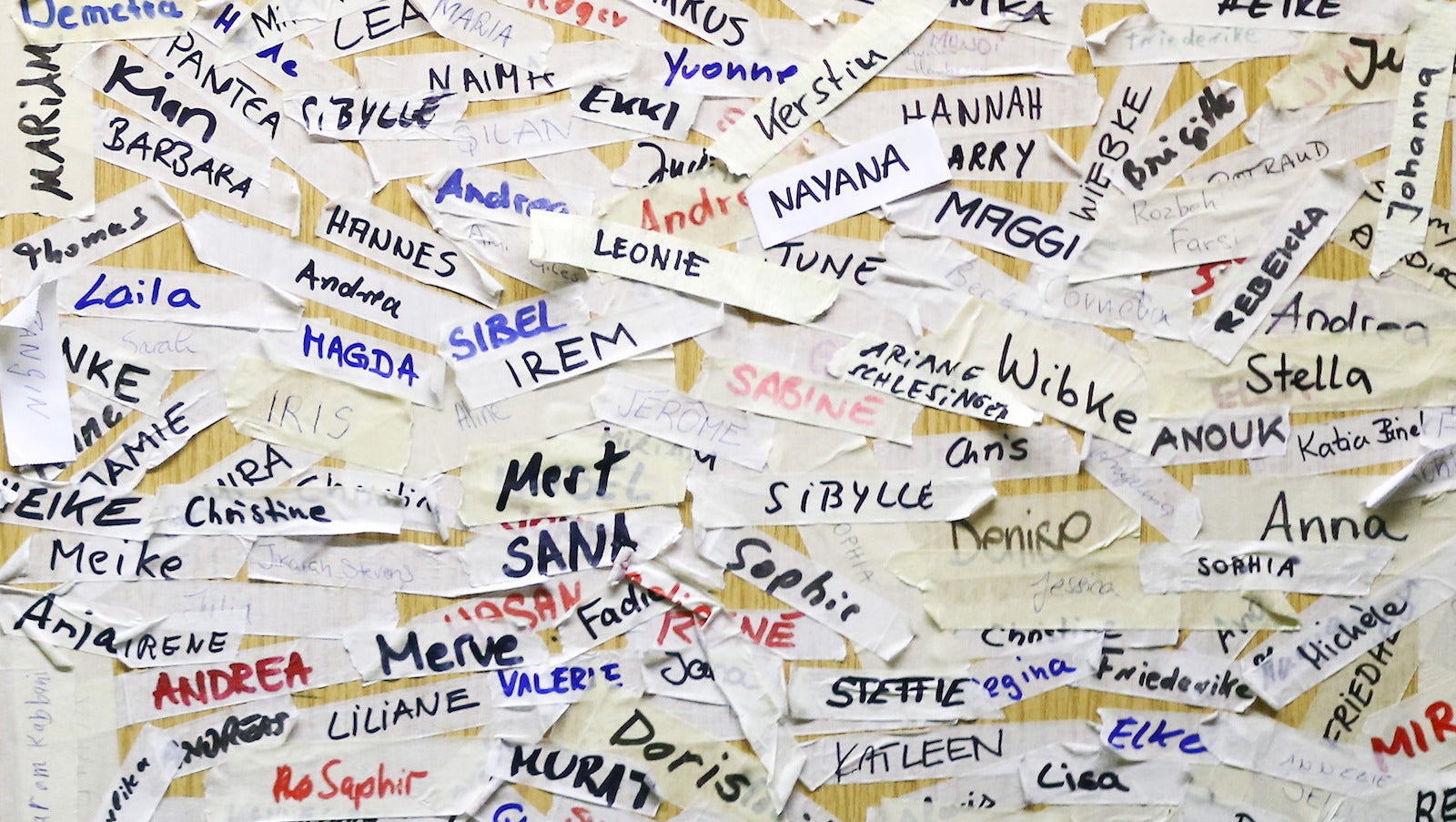

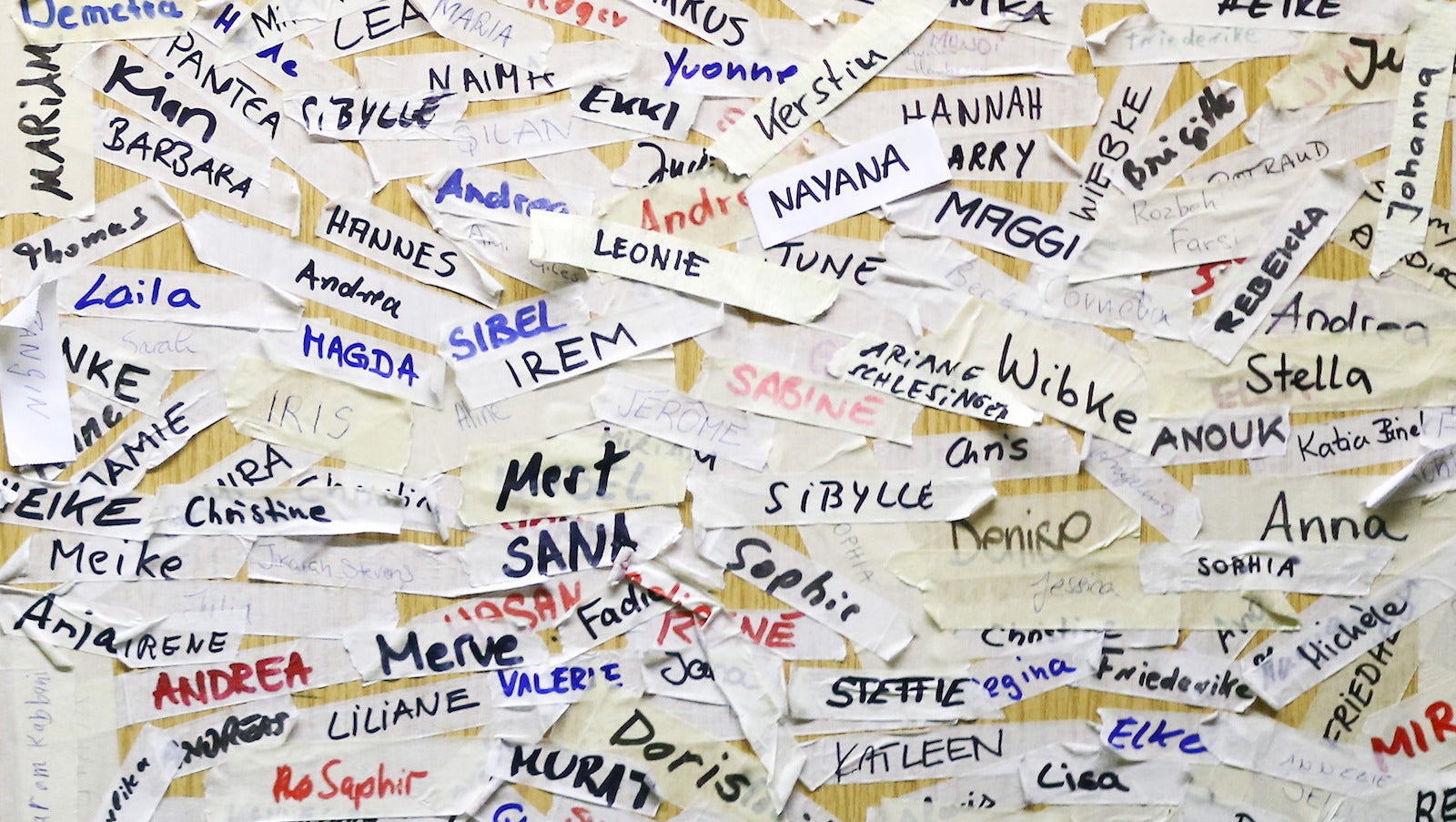

But our names also function in society as the bearers of our personal history. In particular, our surnames can be the markers of our geographic and/or ethnic identity. If we view a list of names, we can usually yoke the name with a national identity or geographical location. For example, consider the following names that announce a mapping in the global community: O’Sullivan, MacLeod, Antonioni, San Miguel, Wong, Chung, Romanov, Van der Haeys, Takamura, Yamamoto, Manoukian, Gosselin. Or consider the following names that identify ethnic origins: Goldstein, Rothman, Muhammed, Abdullah, Bannerjee, St. Croix, Singh.

And what about Ahmad Khan Rahami, the man who detonated homemade bombs in New York and New Jersey over the weekend? After an emergency alert was sent to New Yorkers’ phones on Sept. 19th, identifying him only by name with no portrait, some people felt vilified by the manhunt that ensued for someone whom looked like they fit that description—but of a name, not a person.

Reflexively, we make assumptions about peoples’ ethnic or religious attachments based on the sound of their names. Regrettably, our automatic reactions have led and continue to lead to prejudice, racial profiling, and discrimination, especially in the work place, in educational institutions, and in the political sphere. In large urban centres, like Toronto, New York, or London, where interracial marriages are more common, assumptions based on our associations often lead to unanticipated consequences. For example, we are surprised to encounter a Caucasian woman with the name Marilyn Chang or Susan Obasango, or to greet an Asian man with the name of Patrick Smith.

Vikram Barhat’s BBC article Should You Change Your Name to Get a Job? raises critical and important issues of people with foreign or ethnic-sounding names trying to succeed in a host culture that is no longer inclusive. Barhat mentions several people who have chosen to change their name to “fit in” or to “whiten their identity” by not only name changing but also by modifying their work resumes. He quotes a number of recent studies to support the disturbing finding that there continues to be prejudice in both educational institutions and industries world-wide against those whose identities are “different” or who carry ethnic-sounding names.

Unfortunately, voluntary and involuntary name changing has been a topic for discussion for a very long time. The history of name changing for acceptance and adaptation to a new culture has deep roots. Immigrants move with the hope of finding a better home for themselves, and especially for their children; others hope to escape persecution, oppression, and war. In spite of the guiding principles of equality and democracy upheld by most Western nations, many immigrants and their children today unexpectedly encounter ongoing racism behind closed doors, and explicit or implicit prejudice.

“Changing names is drastic,” Barhat writes. In my recent book, The Power of Names: Uncovering the Mystery of What We Are Called, I address the psychological impact of various types of voluntary and involuntary name changing. In terms of social mores and the melting pot of cultural diversity, to name is a rite of the collective, announcing admission to group membership; and to pronounce one’s name is to automatically reveal one’s ethnic identity.

By contrast, for those experiencing prejudice, to rename is to escape being a discredit, to erase or remove a stigma, to obliterate a difference, or to sanction an affiliation. It is to establish admission into a society without the projected and often real status of being a second-class citizen or a pariah. The desire to reduce racial and ethnic identifications interfering with opportunities for success often appears to outweigh the attachment to a name.

Yet what, if any, is the psychological cost? To change a part of one’s identity that is like a second skin of one’s being—a permanent inscription of our subjectivity—is a profound decision. Certainly, celebrities, artists, and politicians change their names for publicity reasons or to create a name with sex appeal. Women traditionally change their surnames at marriage as a socially sanctioned act. People undergoing religious conversion also may change their names.

However, names changes that are intended to conceal a part of one’s identity fall into a different category. While some people quoted in Barhat’s article appear to quite easily accept their decision to change their name, the experience in my professional practice is otherwise. While modification or changes in one’s name may make a difference on employment and educational application forms, the original name always leaves a trace; the name on that human passport is never completely erased. Eventually the truth of one’s identity is exposed as name-changing seeps through the family tree.

Some of my patients continue to struggle with the changes in their surname made by previous generations in an attempt to hide their ethnic identity while others accept and understand the reasons for the change. Some second- generation children are grateful for their parents’ decisions while others revert to the original spelling in an attempt to reclaim pride in their ethnic identity. Yet all feel that coming to terms with their family and ancestral identity is a piece of psychological work that requires attention.

There are no absolutes here, no right or wrong when discrimination and prejudice in our global world continue to force people from all walks of life to hide or reveal their true identity by name changing. Unfortunately, it is a very tragic state of affairs that in the 21st century, xenophobia and right-wing conservatism have compelled people to lie about who they really are.