100 years ago, New York City declared war against polio and killed 72,000 cats (and 8,000 dogs)

With only 26 cases of polio worldwide this year (as of Sept. 13), the complete eradication of the disease is closer than ever. After decades of devastating populations all over the globe, polio is now endemic only in Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Nigeria, and it’s well on its way to becoming history.

With only 26 cases of polio worldwide this year (as of Sept. 13), the complete eradication of the disease is closer than ever. After decades of devastating populations all over the globe, polio is now endemic only in Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Nigeria, and it’s well on its way to becoming history.

This is the result of a global eradication initiative started in 1988, when there were an estimated 350,000 cases. Thanks to worldwide vaccination drives conducted at times in the most hostile conditions, including in war zones and under totalitarian regimes, the number of cases worldwide has decreased by 99.9%.

The fight to get rid of this disease—that can cause paralysis and, at times, death—is now entering its final stretch. If we do eradicate polio entirely, it will be second infectious disease humans have completely wiped out, after smallpox.

But while in most parts of the world polio is all but forgotten, it wasn’t too long ago that large outbreaks would affect industrialized countries, including the US, where flare-ups of the disease would occur every summer. These outbreaks worsened progressively from the beginning of last century all the way to the 1950s, when polio caused an estimated 15,000 cases of paralysis every year.

In the summer of 1916, New York City was the theater of a spectacular polio outbreak, the largest at that point to occur in the US. The first case occurred in Brooklyn and the disease rapidly spread through the city. Ironically, recently-improved hygiene standards actually made people more vulnerable to the virus, since they were less likely to have been exposed to it and have developed immunity, says David W. Rose, a consultant archivist at the March of Dimes (a nonprofit founded in 1938 by president Franklin D. Roosevelt to fight polio). By the end of the outbreak, New York recorded 9,000 cases of the disease, which caused 2,400 deaths and left 1,000 children paralyzed.

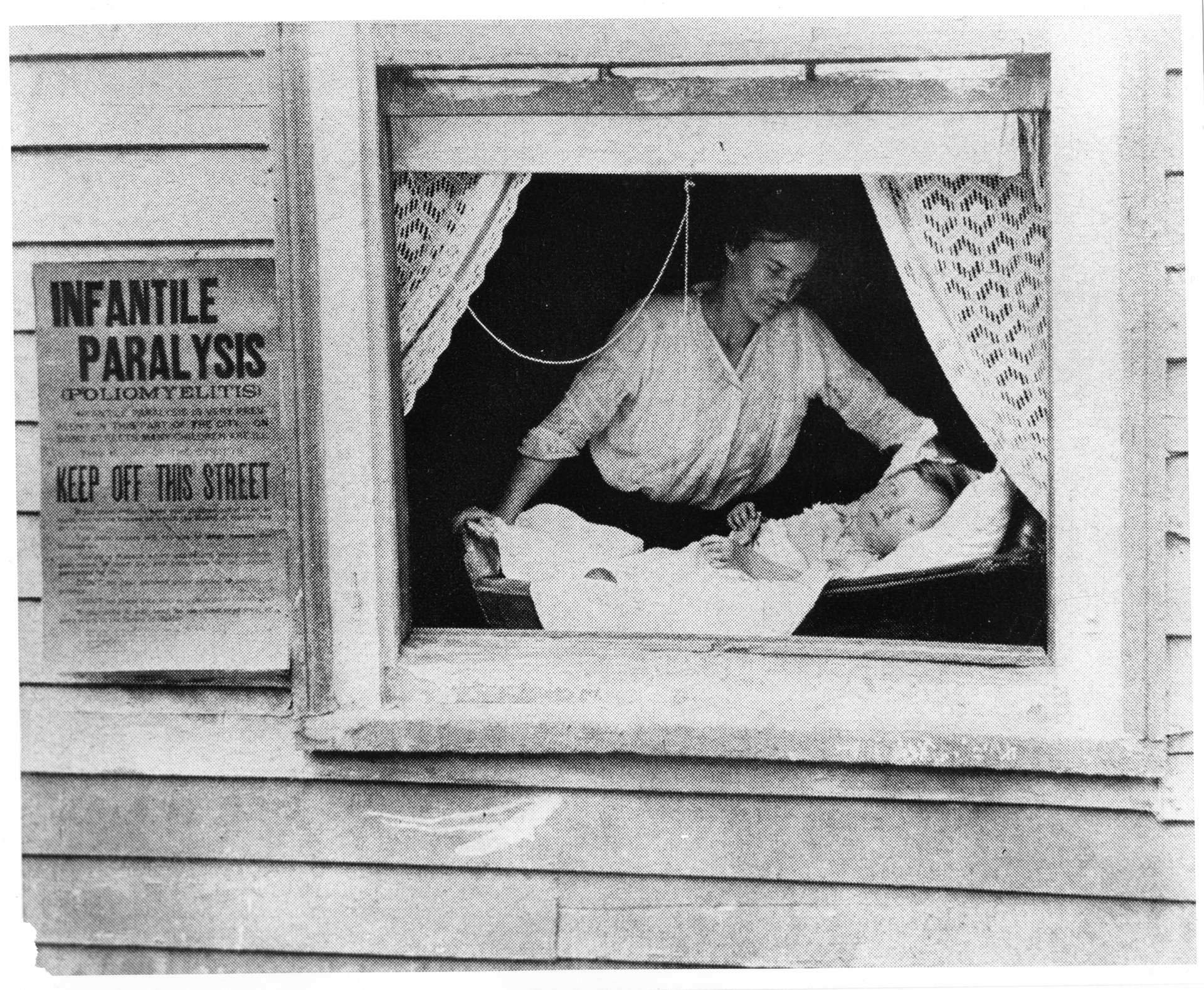

It was panic. New Yorkers were absolutely terrified by the disease, then known as “infant paralysis.” It didn’t discriminate by class or color, and left behind a trail of death and paralysis in a spectacle of horror that appeared to target children with particular viciousness. While often causing just mild symptoms, polio can attack the nervous system and cause permanent paralysis for which—then as now—there is no cure. At the time, Rose says, little was also known about how it spread, and no vaccines were available to prevent it.

Those who could fled the city for rural areas not affected by the epidemic—The Courier-Journal called it “the exodus of the children.”

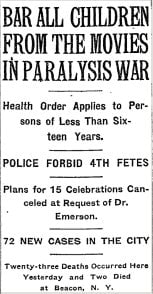

Movie theaters and pools were all closed down in an effort to stop the contagion. “Bar all children from the movies in paralysis war,” blared a July 4, 1916 New York Times headline. But these were typically ineffective measure, Rose says, because the virus usually spread within a household.

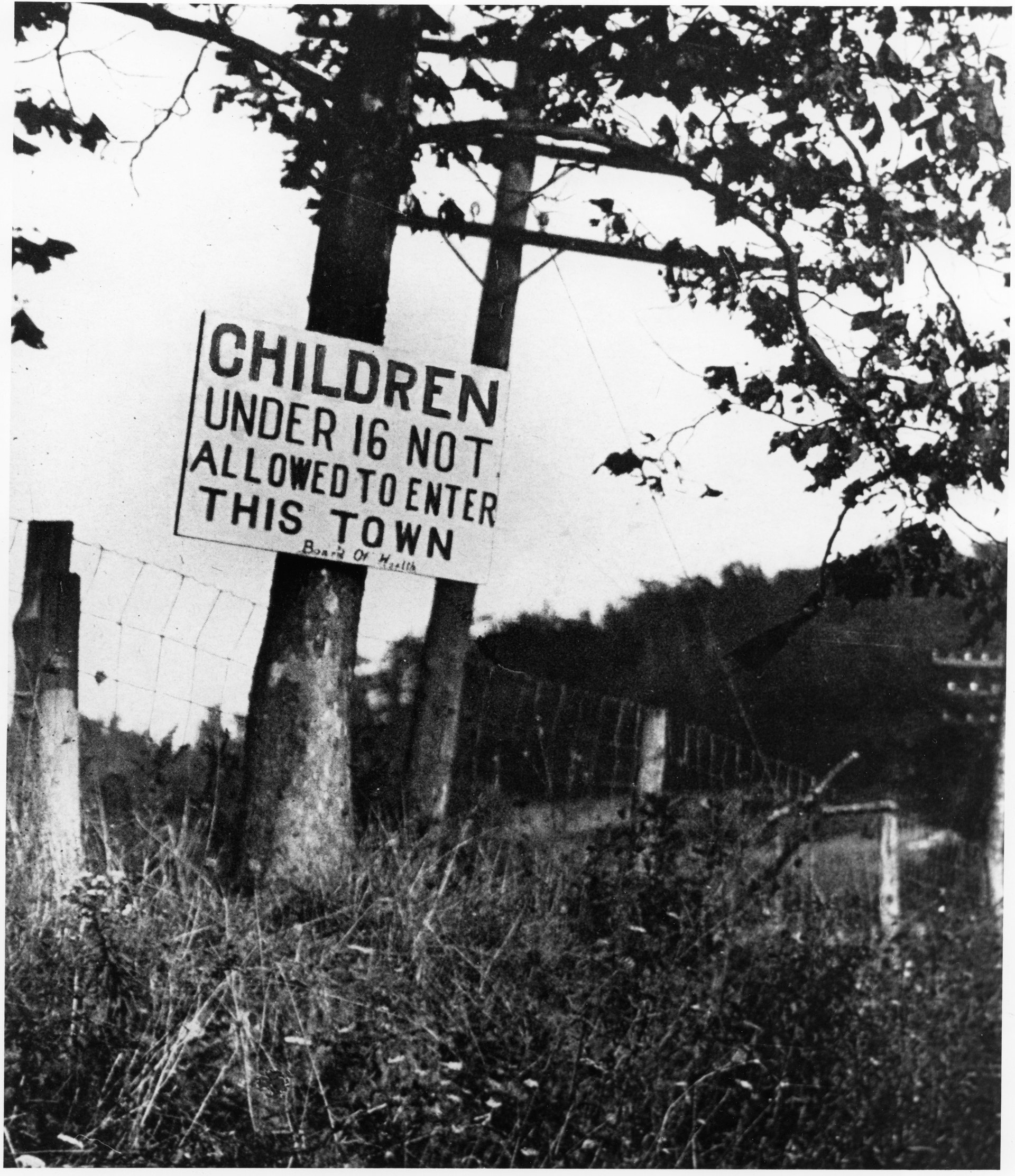

Children who didn’t live in New York were barred from entering town for fear they may contract the disease in the city.

Polio was likened to a plague and the scapegoats were the city’s bugs and mice—even though the polio virus only infects humans, and can only be transmitted through oral contact with an infected person’s stool or saliva droplets.

This misconception lasted all the way up until the 1950s, when health authorities in cities across America would carry on campaigns spraying DDT to kill guiltless mosquitoes during the yearly summer polio epidemics that plagued the country.

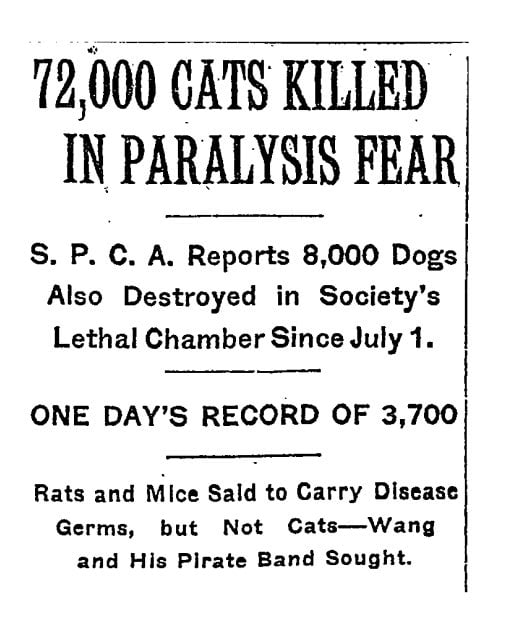

But other innocent animals paid the price of the epidemics, too: thousands of cats and dogs were killed—sometimes as many as 3,700 a day—by, ironically, the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty of Animals (SPCA). On July 26, 1916, the New York Times reported that SPCA representatives said they had collected 80,000 pets—72,000 cats and 8,000 dogs—from owners afraid that they would help spread the disease.

“We have been receiving an average of 800 requests a day for our men to call for unwanted domestic pets, mostly cats, despite the statement issued by the Health Commissioner Emerson that cats do not carry the germs of the disease,” the SPCA’s superintendent told the Times.

People who owned pets let them onto the streets, where they turned into so-called “pirate cats,” roaming the streets and annoying or frightening residents. The SPCA would then be called to collect and kill them in their terrifyingly named “lethal chamber”—a room where they were put down through exposure to a deadly gas.

Some of the cats even became infamous criminals of sorts, like Wang, ”a tailless mauve cat from Formosa” that led a group of 50 to 100 pirate cats that haunted the “pious people” of the Upper West Side, yelling at night, stealing legs of mutton (pdf) from kitchen tables, and scaring the dogs that were meant to frighten them away. Wang’s gang was such a concern that SPCA made a special promise to the Times that its men were “working as hard as they can and there is no doubt that Wang and his band of cats will be rounded up in due course with the other nocturnal nomads in the city.” Whether this was in fact the last of Wang is lost to the annals of history.