The man behind the chart that helped give free trade a bad name says his research was misinterpreted

The negative events attributed to globalization include the rise of Donald Trump, Brexit, trade protectionism, and myriad populist movements that ignore economic realities.

The negative events attributed to globalization include the rise of Donald Trump, Brexit, trade protectionism, and myriad populist movements that ignore economic realities.

But Branko Milanovic, a Serbian-American economist whose work helped give globalization a bad name, wants to set the record straight on the merits of global trade. The problem isn’t trade itself, which overall is a force for good, he says. It’s that countries don’t design smart policies to help the losers adjust to a globalized world.

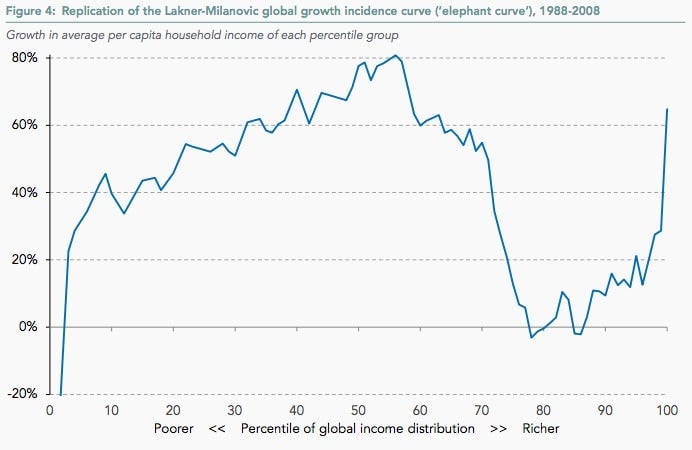

Milanovic and his colleague Christoph Lakner, both inequality experts, created “the elephant chart” (pdf) in 2012, which shows how incomes have changed in the past few decades. The bottom half of global earners earned a lot more in 2011 than someone in the same position in 1988, as did the highest earners. Meanwhile, people in the 80th percentile (who would be considered wealthy by global standards, but the lower middle classes in rich countries) saw their wages stagnate.

The data, which suggests that rich countries’ middle classes have lost out as global trade and globalization have ramped up, has been pounced on to explain populist movements.

Milanovic says his research is being misinterpreted. Income inequality has been created by a combination of globalization, technological change, and domestic economic policies, not just free trade. The City University of New York visiting professor and former economist at the World Bank had this to say:

Global trade is a good thing. Even if you look at the elephant graph, everybody at every point of the distribution had some growth or at worst has stagnated. The use of the word stagnation, strictly speaking means there is no growth or very little growth, it doesn’t mean there is a decline in real incomes.

Trade and globalization are forces for good. The problem is that in many instances globalization is implemented in a way that makes the playing field slanted in favor of the rich. Also the gains from globalization are never likely to be even for all the participants.

A recent study by the Resolution Foundation, a British think tank, reanalyzed the data (pdf) and concluded that globalization (paywall) and trade were being unfairly blamed for rising inequality in rich countries, and that governments deserved more blame for bad economic policy. Finally, it concluded that middle incomes in rich countries didn’t stagnate—they grew.

Milanovic says governments need to focus more on helping people whose jobs become obsolete or less competitive. And while he agrees that stagnating middle class wages in rich countries are partially to blame for populist movements, he points out that there are other factors at play:

There are many other factors too, like the protest vote for its own sake, migration issues; then some people—particularly in the US—might be racially motivated, others might dislike foreigners etc. Thus to explain a political development one needs a much richer tapestry than a single graph.